More innovation needed to help refugees

The short-term vision of humanitarian relief can have unintended consequences

The United Nations global appeal launched last Monday tells a familiar story: The needs are greater than ever before and the financial sum needed to address them, substantial. Humanitarian needs have risen each year since 2011 and global appeal figures have increased in tandem.

In 2014, the UN appeal reached a record of $19.5 billion (Dh71.72 billion), a 50 per cent increase from 2011. And as needs and appeals have grown, so too has the response gap. If we continue on this trajectory, more displaced South Sudanese will be malnourished, more Syrian children will go without education, and more Congolese women and girls will be at risk of domestic violence.

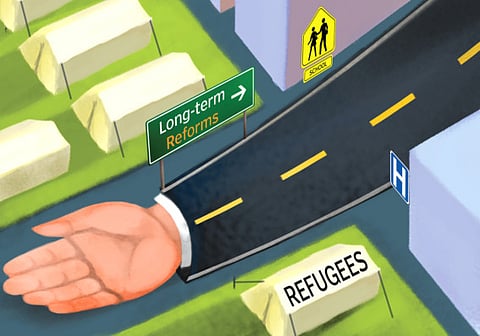

However, the gap will not be met by just more money alone. While a short-term boost is needed to help meet the needs of today’s global poor, there need to be radical and longer-term reforms. Reform is not only essential to improve the impact of aid, but also to spur the confidence of policymakers and the public to increase funding.

The starting point should be to shift aid to the places where it is needed most and where it can make the biggest difference. By 2030, two thirds of the world’s poor are expected to live in states classed as fragile which lack the capacity, will or legitimacy to protect their citizens. Yet, these states currently receive only 38 per cent of total aid. Last month’s announcement by the United Kingdom to increase spending on fragile and failing states from 30 to 50 per cent is welcome. Other donor governments should follow suit, most urgently the United States and other countries in Europe.

Aid also needs to be spent differently. Humanitarian organisations were founded to provide temporary relief, often in remote refugee camps. Yet, the average crisis now lasts for 17 years and the majority of those displaced — more than 80 per cent in the case of Syrian refugees — are not fleeing to refugee camps but settle in urban areas. In this context, the short-term vision of humanitarian relief can have unintended consequences. Temporary shelters, often built on the land that was of least value, turn into long term cities often disconnected from water, sanitation and electricity infrastructures.

There are four critical elements to a better approach. First, development and humanitarian resources must be aligned. In Lebanon for example, more than one million people have fled to cities and towns throughout the country. Refugees now make up more than 20 per cent of the population. The strain this has placed on Lebanon’s infrastructure and social fabric requires humanitarians to depart from the traditional humanitarian offering.

Instead of creating parallel systems, humanitarians need to strengthen water, sanitation, housing, health care and education systems so that displaced people can access the services they need, alongside host populations. At the same time, development actors must keep humanitarian goals in mind, ensuring that vulnerable individuals are able to access services and basic needs.

Second, in urban areas where economic markets are still functioning, most refugees do not need to be given food, clothing and blankets, they need cash. Cash allows them to choose what to buy, slashes the costs for NGOs of transporting bulky goods, and boosts local economies. Unfortunately, despite growing evidence to support this idea, only a relatively small amount of aid — an estimated 6 per cent — is spent on cash transfers.

This illustrates the need for a third reform: For donors to make aid funding conditional on interventions that either generate new evidence about what works, or apply solutions that have already been rigorously tested and publish the cost-efficiency of every programme in their annual accounts. This could have profound consequences.

Finally, if aid donors are serious about reaching more people and making a bigger difference to their lives, greater risk-taking and innovation should be encouraged. While most funding will rightly be tied to results, the aid world also needs a far larger research and development budget dedicated to finding cost-effective solutions that can work at scale. This is crucial to address the dearth of tried and tested solutions to, for instance, reducing violence in the home, or improving governance in unstable regions. In health care, there is need to develop the very systems that deliver vital services such as immunisation to remote, conflict-affected places with weak or non-existing health systems.

Reforms to deliver a more joined-up, cost-effective and evidence-based aid system will take time to set in place. But today’s global appeal will only earn a hearing with the public and policymakers if they see a commitment to better, bolder and more transparent aid.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

David Miliband is president and CEO of the International Rescue Committee. Ravi Gurumurthy is vice-president, strategy and innovation.