Why decades sometimes really do happen in weeks

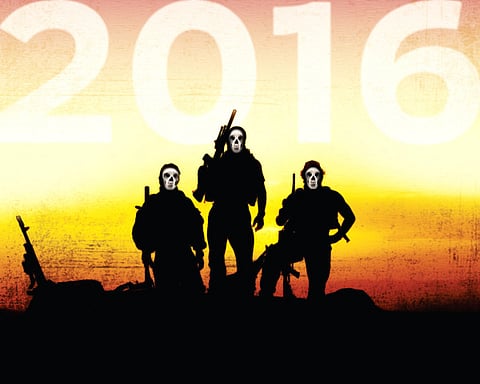

It is not at all clear whether the volatile and anxious summer of 2016 will produce anything like the cascading upheavals seen in years like 1940, 1989 or 2001

Back in the autumn of 1989, as the Iron Curtain was crumbling country by country, some friends and I had an idea for a new college History course. It would be called ‘Europe Since Last Wednesday’.

There are moments in history when time itself seems compressed, when so many shocking and important events crowd together that it becomes almost impossible to keep track of them. Vladimir Lenin supposedly said “there are decades where nothing happens, and weeks where decades happen”. (The remark, alas, is probably apocryphal.) Long before him, the French writer Chateaubriand had quipped that during the quarter-century of the French Revolution and Napoleonic regime, many centuries elapsed. In late 1989, a single three-month period saw the end of Communist power in Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Romania and the fall of the Berlin Wall, as well as the United States’ invasion of Panama, and the Malta summit meeting between Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev and US president George H.W. Bush, where the two leaders essentially announced that the Cold War had come to an end: Many years’ worth of change crammed into a single season.

Are we now living in one of these periods of temporal acceleration? The past few weeks have certainly been vertigo-inducing. On June 23, the British shocked world opinion (and themselves) by voting to leave the European Union. On July 7, five police officers were shot dead in Dallas, prompting fears of widespread unrest in the US. A week later, Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) took credit for the latest massacre to strike the West — a terrorist attack on France’s Bastille Day that killed scores in Nice — and before that event had even started to fade from the media, there was an attempted coup d’tat in Turkey. Then came the police shootings in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. All this took place, moreover, against the background of a horrific sectarian war with no end in Syria, heightened tensions between Nato and Russia and the greatest political upheaval in recent American history, as a populist candidate with no experience in government completed his successful insurrection against the Republican establishment and became the party’s 2016 presidential nominee. Populist authoritarianism is on the rise in many other countries around the world. To recall the famous Chinese curse (as apocryphal as Lenin’s remark), we seem to be living in “interesting times”.

To be sure, nothing in 2016 yet compares to the most truly “interesting” moments in world history. In 1940, in a span of less than three months, Nazi Germany conquered Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and France, while the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. A year later, another three-month period saw the invading Nazis drive hundreds of miles into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic, concurrently beginning the systematic mass murder of Jews and other “undesirables”. During a single two-week period in August of 1945 there took place the end of the Allies’ Potsdam Conference, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet declaration of war on Japan and the Japanese surrender that brought the Second World War to an end.

So far, 2016 has been less “interesting” than 1989, and, for that matter, than 1991. That year witnessed the Gulf War, the attempted coup against Gorbachev, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the assassination of former Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. And then there was 2001, an altogether excessively interesting year for reasons that do not need repeating.

But 2016 is barely half-done, and it is entirely possible that the cascade of events we have been witnessing could accelerate, with unforeseeable consequences. It is worth remembering that disruptive events can trigger others in a variety of ways, even at a great distance. Sometimes the connections are clear; sometimes much less so.

Most obviously, a disruptive event can spark direct imitation. In 1848, after liberal revolutions took place in Sicily and France, a wave of uprisings at least partially inspired by them spread to Denmark, the Austrian Empire, Belgium, and several German and Italian states. In 1968, student rebellions moved across the western world in open imitation of and cooperation with each other, with the climax reached in Paris in May, when an apparent collapse of order led French president Charles de Gaulle briefly to flee to a military base in Germany. In the late 1980s, cracks in the power structure in one part of the Soviet bloc repeatedly led reformers and dissidents in other parts to attempt the same, or to go further. In the autumn of 1989, the satellite regimes fell like the proverbial dominoes, one after the other. More recently, similar patterns have been seen with the “colour revolutions” in the former Soviet Union, and with the Arab Spring. And today, with each terrorist attack, groups like Daesh do their best to publicise what happened, glorify the perpetrators and urge others to emulate these “martyrs”.

But disruption can also multiply because of the opportunities it creates. For instance, military aggression can seem particularly tempting when potential critics or adversaries are distracted by troubles elsewhere. It was hardly a coincidence that Joseph Stalin chose to start occupying the Baltic states on June 15, 1940, just one day after the German army had entered Paris. In August 1968, the fact that the US was reeling from the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr and Robert Kennedy, while mired in a frustrating war in Vietnam, encouraged the Soviet Union to end the “Prague Spring” by force with its invasion of Czechoslovakia.

We still do not know the full story of this year’s attempted coup in Turkey, but it is at least conceivable that the plotters were emboldened to act because of the violent events taking place elsewhere in the world. Given the recent string of terrorist attacks, it would certainly have been more difficult than in previous years for the US and its allies to take serious political action against a Turkish military government that pledged to oppose Daesh and to reverse President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Islamist reforms.

Conversely, anxieties about decline can lead to cascading disruption as well, driving groups or whole nations to take aggressive action in response to a violent event, for fear they will lose the chance to take any effective action at all if they wait much longer. Many historians believe that in 1914, Germany behaved aggressively following the assassination of Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand, driving the outbreak of a general war, due to the belief among German elites that they were losing an arms race to Britain and France. Worse, such anxieties often have very little basis in fact. It is frequently forgotten that in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the Soviet Union was already on life-support, a substantial portion of the American public believed that it was actually an unstoppable behemoth that would soon crush a weak, decadent West. With this diagnosis supposedly confirmed by exaggerated CIA estimates of Soviet capacities, even before Ronald Reagan’s election as president, the US began a large-scale military buildup. Today, although the American economy is in decent shape, and its military budget exceeds that of the next eight countries combined, fears of decline have returned with a vengeance, as exemplified by Donald Trump’s insistence that virtually every other country is supposedly “taking advantage of us”. It is all too easy to see how such largely spurious fears could, in the wrong circumstances, lead an American administration to take dangerously disruptive actions against supposedly ever-more-threatening adversaries.

Finally, widespread disruption, with the wild anxieties and hopes that it generates, can lead to a sense that ordinary rules of behaviour are suspended and that extreme measures must be taken. Since the beginning of the Christian era, hardly a year has gone by without some significant group of Christians insisting that the End Times have arrived. If such a conviction leads to aggressive action against supposed heretics, the resulting violence can lead others in turn to believe in Judgement Day’s nearness, in what amounts to a positive feedback loop of enormous destructive power. Some historians think that something of this sort happened during the Reformation, when Martin Luther’s break with Rome triggered widespread belief in the imminence of the Apocalypse, triggering violent conflict, triggering further apocalyptic belief, and so on. The result was years of bloody religious warfare that decimated much of Europe. Today, the fanatics of Daesh believe they are engaged in an apocalyptic battle between Muslims and non-Muslims for the future of the world and with every atrocity they convince more people in the West that, on this point, they are right.

The pattern is not necessarily religious, however. There are also secular versions of the Apocalypse story. As the Marxist hymn “The Internationale” succinctly declared: “’Tis the final conflict”. A belief that a world-defining struggle has arrived that can lead to a suspension of the ordinary rules, just as surely as a belief that Christ has returned, and produce just as great a cascade of violent disruption from a single event. The 9/11 attacks arguably had such an effect in the US, with the George W. Bush administration coming to believe that it needed to provoke a major war against a non-aggressor state in order to remove what it saw as an existential threat to the world order.

It is not at all clear whether the volatile and anxious summer of 2016 will produce anything like the cascading upheavals seen in years like 2001 or 1989, and whether the current sense of accelerating time will persist. With luck, the current flood tide of bad news will in fact subside and rest of this year will be remembered for placid dullness rather than bloody “interest”. We can hope that the year 2016 will not appear in the titles of the college history courses of the future. But as these historical examples suggest, there are all too many ways that the flames of violence and disruption can suddenly spread and even whip up a firestorm.

— Washington Post

David A. Bell teaches French History at Princeton.