Snoring is the top reason that patients come to see Jennifer Hsia, a sleep surgeon at University of Minnesota Health in Minneapolis. Most of the time, they come in not because they are worried about their health, but because their partner has been complaining about the noise.

“It’s very rare that I have someone come in and say, ‘I think I have sleep apnoea’,” she says. “It’s more, ‘I’m snoring quite badly and my bed partner wants me to do something about it’.”

Even if the person you sleep with doesn’t care, it’s worth seeing a doctor if you snore, experts say. Although there may be nothing to worry about, accumulating evidence suggests a link between snoring and cardiovascular disease. Snoring can also be a sign of sleep apnoea, a more serious disorder that causes people to periodically stop breathing in their sleep.

“All people that have sleep apnoea snore, but not all people who snore have sleep apnoea,” says Ricardo Osorio, a sleep expert and neuroscientist at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York. Getting evaluated is the only way to know for sure.

“If the snoring is bad and you have witnessed apnoeas and there is some suspicion of daytime sleepiness or poor performance at work or risk of car accident because you’re sleeping at the wheel, go to a sleep doctor,” he says. “Generally, the only thing that can happen when you go to a sleep physician is that you can improve the quality of your life a little bit.”

Data is scarce about how common snoring is, Hsia says. But studies from around the world suggest that up to half of people do it.

Snoring happens because our throats are made of soft tissues without rigid structures, Hsia says. As you fall asleep, the throat muscles relax, which causes your airway to narrow. To pass through a now-smaller tube, air then has to move more quickly, producing turbulent airflow that vibrates anything floppy or loose in the back of your throat, such as the uvula or soft palate. That vibration causes the jackhammer-like noise of snoring.

Crushed airways

It’s not clear why only some of us snore, Hsia says. But there are some trends: People become more likely to snore with age, as the throat tissues get looser. Being overweight can crush the airways, raising the risk of snoring. And men tend to snore more than women. Having a drink before bed can also exacerbate snoring because alcohol is a muscle relaxant.

Whether snoring itself is a health concern remains somewhat unclear. In the past decade, some studies have suggested a link between snoring and a higher risk of stroke, based on evidence that people who snore have thicker carotid arteries — a condition called atherosclerosis. But those studies cannot definitely say that snoring is to blame. And other studies have shown no increase in the risk of stroke from snoring.

“That is a grey area where there is a physical finding but we don’t exactly know what it means,” Hsia says. “I think you can safely say there seems to be an association, but you can’t necessarily say at this point that snoring directly causes strokes.”

Some people can snore all night long and wake up feeling great. For others, snoring can disrupt sleep — either by waking the snorer up, or by waking up a bed partner, who repeatedly pokes at the snorer through the night. Interrupted sleep can lead to daytime fatigue, diminished productivity and a risk of car accidents. Inadequate sleep has also been linked to chronic health consequences, such as diabetes and depression.

If you snore and you experience daytime sleepiness even after a full night’s sleep, you may have obstructive sleep apnoea, which affects up to 7 per cent of men and 5 per cent of women in the United States, according to a 2008 study. A more recent study found that, if you include people without daytime sleepiness, rates jump to 24 per cent of men and 9 per cent of women.

Sleep apnoea is like snoring to the extreme: The airway becomes so narrow during sleep that it completely closes off. An alarmed brain then causes a brief awakening. Someone with a severe case can wake up 60 or more times each hour. And during each arousal, Osorio says, the body responds with increased blood pressure and oxidative stress. Damage develops over time.

If untreated, studies show that moderate to severe sleep apnoea increases the likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease. Sleep apnoea may also increase the risk for cancers, diabetes and pregnancy complications, among other complications, including Alzheimer’s disease, according to Osorio’s work.

“You don’t want to sound too alarming,” Osorio says. But he suspects that sleep apnoea creates “an environment that makes the depositing of proteins and [Alzheimer’s] pathology more likely.”

To learn whether you have sleep apnoea, you need to do a sleep study that counts how many times you hold your breath throughout the night and how your oxygen levels drop when that happens. Normally, a sleep study happens in a sleep lab, but many people can do it at home.

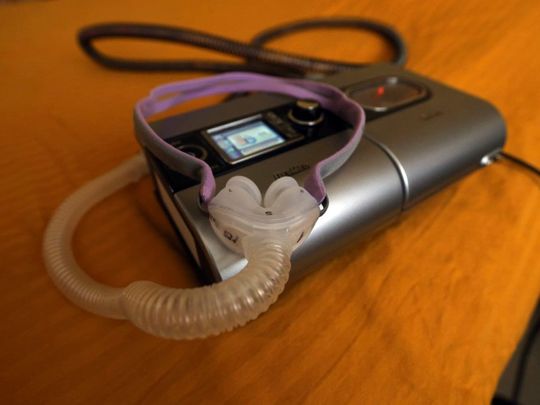

The ideal way to treat sleep apnoea is with a CPAP machine that uses air pressure to keep the airway open during sleep, Hsia says. But compliance tends to be low. For people who can’t tolerate the machine, mouth guards that change the position of the tongue, jaw and other structures sometimes help. Surgery may also be an option.

Dealing with snoring in the absence of sleep apnoea is more complicated, in part because causes differ among individuals, so solutions vary, too. And without definitive research to link snoring with health outcomes, Hsia says, insurance plans don’t cover anti-snoring products.

To avoid paying for products that don’t work, she recommends visiting a doctor to sleuth out why you snore. Then — as long as sleep apnoea is ruled out — start with an inexpensive product before committing to a more high-end version.

For example, many people find that their snoring is worst when they lie on their backs. In those cases, Hsia suggests putting a few tennis balls into a cheap fanny pack and strapping it onto your waist, keeping the balls against your back. When you roll onto your back, the balls will cause enough discomfort to make you roll back over.

If staying on your side controls the snoring, you can invest in nicer pillows or foam blocks that are designed to work as body positioners. Some products achieve the same result with vibrations that alert a sleeper every time he rolls onto his back.

If your snoring is caused by nasal congestion, on the other hand, it might take medication to control allergies or even surgery to fix a deviated septum.

For some people, losing weight below a particular threshold resolves snoring. Others benefit from a mouthguard, although over-the-counter versions tend to be one-size-fits-all, which makes them uncomfortable for most, Hsia says. If a cheap mouthguard works after a couple of nights, dentists can create custom versions that feel better.

It might take some trial-and-error to find the right solution. “It’s a ‘different-things-are-going-to-work-for-different-people’ kind of a situation,” Hsia says. “It is worth getting looked at because there’s no one fix for every person.”

How snoring has managed to persist through evolution remains an open question. Hsia says she wonders whether snoring was once seen as a sign of being a good sleeper, and only now do we realise that it might not be so great. There’s another possibility, too: By the time someone is sound asleep and snoring, the passing on of genes may be already complete.

–Washington Post