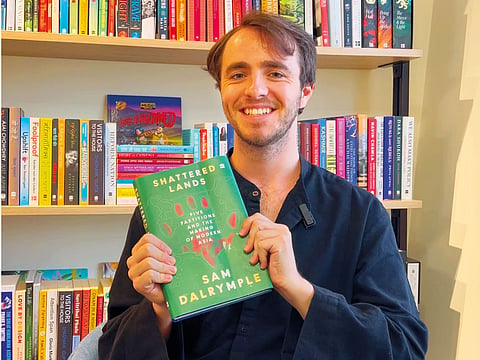

From Physics to Partition: Sam Dalrymple's quest to reconnect lost histories

Shattered Lives offers insights into forgotten partitions & the hope embedded in history

In a sense, the seeds of Sam Dalrymple’s debut book were discovered in an attic in North London. While interviewing an elderly man about his memories of the Indian subcontinent’s partition, the noted author, filmmaker, writer and historian was told, almost offhandedly, “There’s also an old diary lying upstairs. You might want to take a look.”

Dalrymple found a Punjabi-language journal, written daily in Gurmukhi script by a Sikh miner named Uttam Singh, recounting a perilous trek from Burma’s Shan State to Imphal during a wartime exodus.

“This diary was extraordinary,” the author recalls in an interview with Friday. “Most accounts of the exodus from Burma are by Europeans, Anglo-Indians, or bureaucrats who had cars, trains or boats. This was the voice of someone on foot: an ordinary miner, recording the hunger, exhaustion and loss as people walked across jungles and mountains.”

New insights into historic refugee crisis

For Dalrymple, the discovery was transformative. The find became one of the sparks behind Shattered Lands - Five Partitions and the Making of Modern India, Sam’s sweeping history of South Asia’s partitions. The book traces not just the much-written-about subcontinental partition of 1947, but also lesser-known partitions of an empire that once stretched from Rangoon to Yemen. More popularly known as the British Raj, it disintegrated in less than 50 years, resulting in a dozen modern nations.

The diary is now preserved in the British Library, where it offers a rare, ground-level view of one of South Asia’s most forgotten refugee crises. “It’s one of the most important documents I’ve come across,” he says. “It gives us a perspective that elite histories simply cannot.”

Shattered Lives explores how “maps were redrawn in boardrooms and battlefields, by politicians in London and revolutionaries in Delhi, by kings in remote palaces and soldiers in trenches.” It gives us a new look into modern Asia and its history. Along the way, the book also reveals enough documented incidents and facts to leave any lover of modern history slack-jawed in wonder while offering new and fascinating insights into the making of nations.

From physicist to historian

Although he grew up surrounded by history, Dalrymple’s journey to becoming a historian was anything but predictable. “My father [William Dalrymple] is a historian, and I was raised among writers. My childhood was unusual for a Scottish kid — 22 of my 28 years spent in India, being dragged to Rajasthani hill forts or to Baul singers in Bengal. That shaped everything,” he says with a laugh.

It also clearly shaped his writing style. “I wanted to write narrative history, rigorous and sourced, but accessible... not dry academia. That’s influenced by my father, but also by people like Anchal Malhotra, who taught me how to handle family histories with care.”

But history was not his first choice. “When I was younger, I wanted to be a particle physicist,” he says. He nearly realised his dream when, as a teenager, he landed an internship at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. “I was thrilled, convinced physics was my future.”

Then came a family trip to Bamiyan in Afghanistan that left him “blown away”. He started teaching himself Farsi through books, and that changed everything, the author says. He also studied Sanskrit in college.

Even so, his first university applications were for physics. When he didn’t get into his school of choice, he took a gap year, studying Persian from a professor in Old Delhi. That opened doors he hadn’t known existed. And at 18, in a burst of adventure, he boarded the bus from Delhi to Lahore.

“I don’t think that bus even runs anymore,” he says. “But arriving in Lahore, I was stunned. It looked so much like Delhi. And I thought: how is it that the city most similar to Delhi lies across a border [in a different country]? From then on, there was no turning back.”

That sense of loss and connections across borders took shape in Project Dastaan, which Dalrymple co-founded with friends from Oxford University, where he graduated from. The idea was sparked by friends on opposite sides of the border who could easily visit each other’s homelands – but not their own because they lay in different countries.

The peace-building initiative launched in 2018 to virtually reconnect survivors of the 1947 Partition of India with their ancestral homes across modern India, Pakistan and Bangladesh through 360-degree digital experiences and oral storytelling. “We scanned ancestral homes, mosques, temples, gurdwaras,” he says. “Imagine a 95-year-old putting on VR goggles and walking through their hometown again. Many couldn’t travel because of politics or age. But through technology, we gave them that chance.”

About 30 families were reconnected with their ancestral homes and the project was embraced on both sides of the border. “Perhaps because it was about the elderly, it seemed less political, more heartwarming,” he notes. Collaborations with the Partition Museum in Amritsar and the Lahore Museum of National History gave the effort archival legitimacy.

The project also pushed Sam deeper into history. “Growing up, I thought Partition only meant 1947,” he says. “But when I asked someone from Tripura about it, they said, ‘Which partition?’ For them, there were three: Burma in 1937, Pakistan in 1947, Bangladesh in 1971. Each reshaped their lives.”

Further research showed him how much had been left out of mainstream history. “Look at maps of British India in the 1920s and you’ll see Burma, Aden and several other places listed alongside Jaipur and Mysore.” Some regions beyond Rangoon too were princely states under the Raj. “Most people [in those far-flung areas] assumed their ties were to London. In reality, they were administratively linked to Delhi,” Dalrymple says.

His book explores the close links these states shared with India even though they were geographically distant from the subcontinent. The historian also challenges an enduring Partition story: that Cyril Radcliffe single-handedly drew the India-Pakistan border. “We always call it the Radcliffe Line,” he says. “But the truth is, Radcliffe only drew about 18 per cent of the modern India-Pakistan border, the section dividing the two Punjabs. The other 80-plus per cent was shaped by around 20 princes who ruled the borderlands.”

These included the Maharajas of Kutch, Jodhpur, Kashmir and the Nawabs of Bahawalpur and Khairpur. “They were given the choice of which country to join. Had they chosen differently, the map would have been utterly different. For instance, both Jodhpur and Jaisalmer considered joining Pakistan, while Bahawalpur and Khairpur considered joining India.”

There were several ‘oh wow’ moments during his research, as a shock of hair falls over his forehead, including finding the diary and letters to prime ministers.

“One of the most startling findings was that Arabs in Yemen were once legally considered Indians. The Gulf and Yemen were protectorates of the Viceroy, and Arab was seen as an Indian ethnicity, just like Gujarati or Bengali,” he says. “There was even a moment in the 1940s when those states could have joined an independent India.”

Borders as lived realities

For Sam, history is not about maps but about lived experience. “I’ve realized how arbitrary borders are,” he says. “Half of Delhi today has roots from across the border while half of Karachi’s people once lived in Delhi. Even Reliance, India’s biggest business, was built by a generation of Indians who left Aden in the 1960s. So even the most ‘Indian’ institutions have multinational stories.”

What lessons does he hope readers take away? “We often treat these conflicts as eternal, unsolvable. But remembering how recently these borders were drawn shows us they’re not immutable. With creativity and trust, things can change. With creativity, there is hope. These conflicts don’t have to last forever.”

He points to Ireland as an example. “It too was partitioned along religious lines. My parents grew up in a world where being Catholic mattered deeply. For me, it barely registers. The conflict that once seemed permanent has largely faded in my lifetime.”

Before gets onto his next project, there are book tours to complete, stretching from London to India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and, he hopes, perhaps a visit to Dubai. “I’d love to come,” he says, smiling. “I love the beach and the city.”