River Phoenix died 25 years ago: Why we should never forget

In his short 23 years, the young actor managed to be many thing — an Oscar nominee, a hearththrob, an environmentalist and animal rights activist

Here, on the corner of Sunset and Larrabee in West Hollywood, California, River Phoenix was carried out of the darkened recesses of the Viper Room nightclub in the early hours of Halloween 25 years ago. “He was essentially liquid,” one witness said. He died on the sidewalk where he collapsed, a victim of metabolised heroin, cocaine and Hollywood excess.

He was 23. He is forever 23.

In those 23 years, Phoenix managed to be many things. He was a star — a serious actor with an Oscar nod for Running on Empty, and a cult following for Stand by Me, but also a heartthrob staple of Tiger Beat. He was a staunch environmentalist somewhat ahead of his time, and an outspoken animal rights activist. He was an aspiring musician with a beguiling back story — a peripatetic childhood in a notorious cult with hippie-idealist parents and four gifted younger siblings.

Phoenix has strangely slipped away from us — grieved but rarely celebrated anymore. His death was quickly overshadowed by Kurt Cobain’s suicide and other grunge-era tragedies; his movies fell off the cultural radar. The other beautiful, talented boys of his day gained gravitas and intrigue as they matured into A-list stars. It is harder than ever to imagine Phoenix in middle age, but also, perhaps, unnecessary.

He died of speedballing but spent his life as a proselytising vegan. He once fled a restaurant in tears after girlfriend Martha Plimpton ordered shellfish.

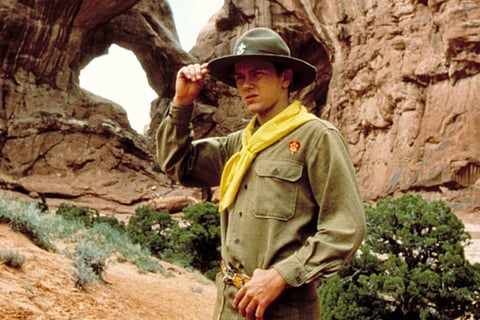

Like many teenage icons, Phoenix was slim and impossibly pretty, with a perfect ski-jump of a nose, and a blond curtain cascading over his sombre face. He rarely smiled in films, early television performances or photos. Sullen was a speciality. Interviews were an exercise in pain.

The darkness, it was understandable. His parents — young, poor and searching — drifted in his early years. They took their surname from the mythical bird and christened their children with similar flair: Rain, Joaquin, Liberty, Summer. The eldest of the five children they had together was named after the river of life in Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. When River was a toddler, the family joined the controversial Children of God religious movement, a journey that took them from Florida to Mexico, Puerto Rico and Venezuela. He later spoke of sexual abuse he suffered during his early years in that faith. When the family broke away from the cult and landed in Los Angeles, the children sang on the streets to help earn a living. They signed with a talent agent, and Phoenix landed his first commercials at age 10.

By adolescence, Phoenix was a veteran of standard ‘80s television fare — a one-season series (Seven Brides for Seven Brothers), a guest spot on Family Ties, an after school special (about dyslexia), a made-for-TV movie (domestic violence), and a miniseries (the Kennedys).

His big-screen breakthrough came in Reiner’s Stand By Me, a coming-of-age drama starring a passel of other young actors-to-watch, about a group of boys who discover a corpse in the woods. It was released in 1986, a few weeks before Phoenix’s 16th birthday. Phoenix looked even younger but projected the soulfulness of someone much older.

He worked opposite Helen Mirren, Robert Redford, Sidney Poitier, Kevin Kline, Tracey Ullman, Dan Aykroyd, Richard Harris and a pre-stardom Sandra Bullock. His directors included such luminaries as Gus Van Sant, Steven Spielberg and the late Sidney Lumet. He holds the distinction of playing both Harrison Ford’s son, in The Mosquito Coast, and portraying the young version of a Harrison Ford character, in a 10-minute cameo in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Even amid such daunting company, Phoenix quickly arrived at the point where his name appeared first on the screen.

His looks, and his legion of teenage fans, often caused colleagues to underestimate his talent at first.

His best performances — Idaho, Running on Empty, Dogfight, Stand By Me — are rarely watched or cited. Phoenix never had a John Hughes movie, a superhero flick, a Ghostbusters or Dead Poets Society. He was too methodical to work in catchphrases.

His peers — Hawke, Leonardo DiCaprio, Keanu Reeves, and Johnny Depp — kept working. They’re middle-aged and somewhat wrinkled, having successfully transitioned from young phenomena to Hollywood heavyweights.

Joaquin Phoenix, younger by four years, was 19 when he helped carry his brother out of the Viper Room. He’s 44 now, an acting titan who never had to bother with teen celebrity, the crush of adoring fans.

Phoenix’s official cause of death was “acute multiple drug intoxication.” The Los Angeles coroner found high concentrations of cocaine and morphine — heroin — in his system, as well as Valium, marijuana and ephedrine, an ingredient in over-the-counter cold medications.

“People talk about him having such a clean life. I think that’s not right ... He didn’t die from carrot juice,” his publicist told The Washington Post after his autopsy.

Tourists still flock to the Viper Room to see where Phoenix spent his final hours. Many visitors apparently believe that Depp — enshrined in a photo behind glass near the bar — is still a co-owner, but he disposed of his share more than a dozen years ago. The club has been bought and sold several times, most recently this summer in an $80 million (Dh293.79 million) deal bundled with several adjacent properties.

This Halloween, the 25th anniversary of Phoenix’s death, the all-girl rock trio Tsu Shi Ma Mi Re from Japan is scheduled to play. There are no official plans to commemorate Phoenix — that’s not the way the Viper Room rolls — but fans often appear on the last night of October outside the club’s Sunset entrance with candles and notes, wine bottles and teddy bears to create a sidewalk memorial. “It’s beautifully sad,” notes general manager Tommy Black, as a way of honouring a star who has now been dead longer than he was alive.