Beyonce and Jay Z get loud with social responsibility

Superstar couple and music greats are increasingly using their outsize platform as a tool of social agitation

In 2012, the singer, actor and civil rights leader Harry Belafonte indicted, among others, Jay Z and Beyonce as being part of a generation of black artists who have “turned their back on social responsibility.” It was a rare public upbraiding for a couple who had so effectively shifted American pop culture, but whose work for social change was primarily rooted in what they accomplished on record, not off.

Four years later, the social landscape has shifted: Politics have moved from the implicit to the explicit, and culture is following in tow — helped in no small part by Jay Z and BeyoncE, who are increasingly using their outsize platform as a tool of social agitation. In the wake of the police killings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling this week — but before news broke of the shooting deaths of five police officers in Dallas — both released bold statements, weaving together their activism and their art.

Beyonce posted a staunch statement of frustration on her website: “These robberies of lives make us feel helpless and hopeless,” she wrote, “but we have to believe that we are fighting for the rights of the next generation, for the next young men and women who believe in good.” At her concert in Glasgow, Scotland, on Thursday night, she sang her rousing political anthem Freedom a cappella in front of a screen bearing the names of police brutality victims.

Late on Thursday night, on his streaming service, Tidal, Jay Z released Spiritual, a song motivated by anger — and exhaustion — about police brutality, in which he repeats the refrain “Just a boy from the ‘hood that/Got my hands in the air/In despair, don’t shoot.”

Belafonte’s critique came just a few months after the birth of Blue Ivy, Jay Z and Beyonce’s daughter. That their newly outward focus on social justice coincides with their years raising her isn’t a surprise — who wants to make the world a better place more than a parent? A child gives purpose.

And hearing Jay Z rap about his daughter in recent years, in ways both ecstatic and restless, has been the main pleasure of what’s almost certainly the twilight of his rapping career.

In 2013, on the song Jay Z Blue, he presented himself completely free of bravado. He detailed his fears — Can someone who was never properly fathered become a worthy father? Can a parent ever truly protect a child? — and foreshadowed the marital tensions that his wife, Beyonce, would later mine so effectively on her 2016 album, Lemonade.

All the same themes are there on the frenzied, fragmented Spiritual. But this time, it’s not domestic strife threatening Blue’s calm, it’s what’s happening in the rest of the world. What unnerves Jay Z is that you can improve your own behaviour, but you can’t control anyone else’s: He can’t fix persistent police violence against black bodies.

I’m smack dab/In a hurricane of emotions/Can’t even raise my little daughter, my little Carter/We call her Blue ‘cause it’s sad that/How can I be a dad that, I never had that/Shattered in a million pieces, where the glass at/I need a drink, shrink or something/I need an angelic voice to sing something/Bless my soul, extend your arms, I’m cold/Hold me for a half-hour ‘til I’m whole

In a note that accompanied the release of Spiritual, Jay Z said he wrote the song some time ago, before the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 galvanised the Black Lives Matter movement. “I’m hurt that I knew his death wouldn’t be the last,” he wrote. “I’m saddened and disappointed in THIS America — we should be further along. WE ARE NOT.”

In 2016, Jay Z is less an essential figure in contemporary hip hop than an exemplar of the possibilities a life in the genre can afford. But as Spiritual makes plain, even he can feel helpless: “This is tougher than any gun that I raised/Any crack that I blazed, that was nothing.”

Jay Z’s emergence as an activist, from sub rosa to out in the open, has been the quiet counterpoint to his very public entrepreneurship in recent years. He helped Brooklyn Nets players secure I Can’t Breathe T-shirts to wear following the police killing of Eric Garner. He and Beyonce reportedly contributed money to bail out arrested Baltimore and Ferguson protesters. He announced that he would funnel money to a variety of social justice groups from proceeds raised in a charity concert given by Tidal last year.

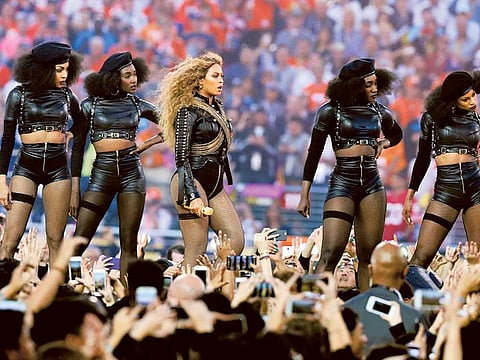

Beyonce’s activism has been more closely tied to her art. Early this year, she released Formation, on which she sang intensely about black beauty and cultural pride. In the video, a dancing black boy induces a row of armed officers to raise their hands in surrender, and Beyonce herself is draped atop a police cruiser as it sinks into the water. Her vigorous Super Bowl halftime show performance of the song included nods to the Black Panthers; it was the most widely seen act of political art in recent memory.

Of course, it inspired protests. At concerts on her current Formation tour, she sells a T-shirt that reads “Boycott Beyonce” — a taunt and a wink.

For Jay Z and Beyonce, speaking loudly has become the new normal. As much as parenting is love, warmth, astonishment and joy, it is also unease, uncertainty, humility, fear. Jay Z and Beyonce are confronting those feelings head-on — it’s their way of building a bridge to the past and securing a road for the future.