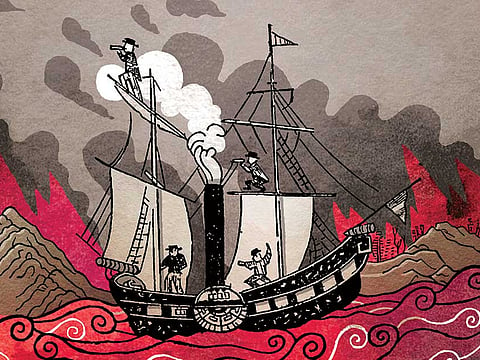

Book review: Flood of Fire by Amitav Ghosh

The third book in the Ibis trilogy, set in the backdrop of the Opium Wars, brings all the characters back, joining the dots to complete the picture

Flood of Fire

By Amitav Ghosh, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 624 pages, $28

What do you do when a seven-year journey comes to an end?

The feeling I had was one of utter emptiness.

For the last seven years, Indian writer Amitav Ghosh has regaled us with his epic Ibis trilogy, starting from the poppy fields of Ghazipur in British India’s United Provinces, to the landing of the shipments in Hong Kong, and now he has given us the culmination, “Flood of Fire”, where the Opium Wars begin between Imperial China and British India.

Two distinct strands have now emerged in the popular genre of Indian writing in English. One is that championed by writers such as Amish and Anand Neelakatan, who have sought to revisit the country’s treasure trove of mythological lore and its epics. The other strand explores more contemporary times, of which Ghosh is one of the foremost exponents.

For the uninitiated, Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy is a politico-historical series that started with the 2008 publication of the first book, “Sea of Poppies”. This book brings together a motley group of girmitiyas — the name being a corruption of the word agreement — that Indians used to sign when leaving the country to work as indentured labourers overseas.

The protagonist in this book was Deeti, a high-caste widow whose husband worked in the opium factory at Ghazipur. She fled with a low-caste cartpuller Kalua as she was about to be burnt alive on her husband’s funeral pyre in observance of the decadent Hindu practice of sati.

Along with them, there was Paulette, a British girl who fled her adopted family after her botanist father’s death, Zachary Reid, an American ship’s mate who falls in love with her, and two convicts, one being a former “zamindar” (landlord) who failed to pay his debts. All these characters are set aboard the Ibis, a schooner owned by a prominent British opium merchant. The book ends with five people, including the two convicts and Kalua, escaping from the ship after a mutiny in which the security chief, who happened to be the elder brother of Deeti’s husband, is killed by Kalua.

The second book in the trilogy, “River of Smoke”, takes us to the island of Hong Kong, the main port of call for opium-laden ships to sell their ware in China. The main character in this book is Bahram Mody, a Parsi merchant who happens to be the biological father of Ah-Fatt alias Freddie, the other convict on board the Ibis who escaped.

This book gives us the first rumblings of trouble in Hong Kong regarding the opium shipments, with the Chinese bent on blocking them to tackle the rising addiction to the drug in the country, and the British seeking to protect their wares in the name of free trade.

In the end, Bahram commits suicide as his entire cargo is confiscated. We get fleeting glimpses of Deeti and her brood after the rest of the party landed in Mauritius, Paulette moving to Hong Kong under the protection of a botanist friend of her father, and Neel, the landlord, who emerges as a cashier to Mody, and it is known that the escapees had landed in Singapore.

In “Flood of Fire”, the characters start coming back together, in one place, and the dots get joined page by page. New characters enter, the most important being Kesri Singh, Deeti’s elder brother, older ones mature, as Reid turns a ship’s carpenter to repair the vessel that was confiscated as part of Neel’s debt to Burnham, and ends up having a dalliance with Burnham’s wife.

The Ibis sails again from Calcutta, with the Burnhams and Reid in tow for Hong Kong, where the stage is being set for the British expeditionary force to challenge the Chinese government’s decree banning the opium trade.

The name of the book is derived from the heavy bombardment from the British navy’s ships on the Chinese vessels and forts in the first salvo of the Opium Wars. The book ends with some happy, some sad endings — Burnham’s wife takes her own life, Reid and Paulette unite, Neel unites with his son, Kalua and Kesri come to know each other, and run away with a group of sailors with the Ibis to Mauritius.

Ghosh’s final act in the Ibis trilogy is a masterpiece in storytelling. From the political nuances surrounding the opium trade, the caste issues and its repressive consequences in India, to the light-hearted banter and dalliances of the characters, the “Flood of Fire” never ceases to keep the reader hooked.

The reader gets a glimpse of the life and times in early British colonial history in India, and how thousands of impoverished men joined the British army simply because it paid salaries on time and provided a pension. The high point of the book, indeed the entire series, is the Anglicised corruption of Indian words — budgerow (“bajra”, an Indian riverine vessel mainly used for pleasure trips), gudda (“gadha”, donkey), puckrowed (“pakro”, to catch hold of) — and several others, which made its way into colonial vocabulary as the British set themselves up in India.

However, I felt the book ended rather abruptly, and would have preferred the final flight of the protagonists on the Ibis to Mauritius be told in a more detailed manner. This is more so as in the previous two books, as well as this one, there is reference to a cave in Mauritius which is referred to as Deeti’s shrine, where she drew pictures of the events mentioned in the books. So, it probably would have been more fitting if the reader had a little more detail about the event between the flight of the Ibis and Deeti’s reunion with Kalua.

These are but small hiccups in an otherwise eminently readable masterpiece. With the end of the Ibis trilogy, Ghosh has sealed his position as one of the finest exponents of Indian writing in English.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox