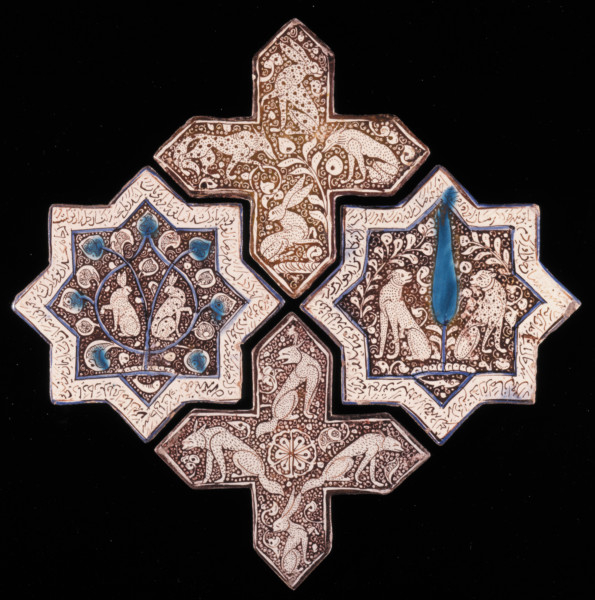

It’s small. About 20 centimetres at its widest. A tile shaped like stars with two lovers surrounded by blue birds and dancing fish. Around it a Persian verse reads:

Last night the moon came into your house, filled with envy. I thought of chasing him away. Who is the moon to sit in the same place as you.

This piece of ceramic from the 13th century is by no means the most eye-catching piece among the lustrous array on show at the British Museum’s new Islamic World galleries but it is one of the most beguiling. In its disarming way, it is a corrective to a contemporary image of Islam as “a malignant cancer” as US President Donald Trump once notoriously described it — an image nonetheless that has been encouraged by the intolerance of some and the barbarity of others.

Another ceramic tile, from about 1308, is decorated with birds, leaves and flowers and has part of a text from the Quran (78.9) which reads: ‘wala shukur.’

It was a part of a wall of tiles designed for the shrine of an Iranian prince but at some stage, no one knows when and by whom, the tile was defaced. The heads of the birds were chipped off.

It is as if a religious leader had realised that such figurative images had no place alongside words from the Quran as the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) had decreed when he banned images of humans and animals on religious and official texts. He feared they would be a distraction to prayer. Interestingly, when he took Makkah in 630 AD and founded the Islamic state he destroyed all the idols but kept an image of the Virgin Mary and Jesus because they were not an object of worship.

The scratching out of the birds resonates all too well with the recent history suffered by some regions of the Islamic world, the despoiling of Palmyra by Daesh guerillas, the blowing up by the Taliban of the Bamiyan Buddhas which had stood for centuries, the strife and destruction which has engulfed cities such as Baghdad, Samara, Mosul. The list is endless.

But what our love birds demonstrate is that the Islamic world, the world of the craftsman, the thinker, the common or garden artisan, was responsible for fabulous outpouring of creativity from those very places and what the new galleries help to achieve is an understanding of Islam and a corrective to the misconceptions about it that so many have.

What those ignorant about Islam might find striking is the amount of figurative work on show.

In fact, rather than destroy everything that had come before whether Roman, Byzantine or Christian, the prophet assimilated the styles of the early cultures such as Yemen, early converts to Islam and home of the legendary Queen of Sheba and a major trading centre. Textiles came from Egypt, buildings and crafts were adapted from the Byzantine Empire which lost control of Syria and Palestine in 643. A fragment of a 13th-century flask in gilded and enamelled glass decorated with flowers, birds and strange animals testify to the enduring influence.

All these are from the British Museum’s own collection, hitherto dispersed in distant corners of the building but brought together with the support of the Malayan-based Albukhary Foundation. The result is a radiant glow of greens, pinks and blues — lots of blues — metal work in gold and silver, coins from the times of the Crusaders (1099-1187), all in a swirl of fabulous creativity. The myth that all figurative art was banned is shown to be just that, a myth, that music was forbidden, dance a sin, that lightness and beauty, was somehow to be frowned on is confounded.

But this is not just about the art or the religion nor is it about the dynasties that come and go over the centuries rather, as the title of the gallery suggests, it is about the world of artisans and craftsmen who did not necessarily follow any hard and fast rules, who were by no means all Muslim, but who sustained a culture and worked with a rich figural history that already existed and altered it as influences flooded in from the furthest corners of the empire.

It is a culture which has stretched across the centuries from the 7th century to the present day and as Venetia Porter, assistant curator, Islamic and contemporary Middle East, explains: “The galleries are not just about high art, not only for the royal courts or for religion. They show that ordinary people as well as those in the court rose to the surface with their skills. Our collection has made us think about what art is and we have included a lot more things such as textiles and contemporary art and made sure everything has an equal value.”

She emphasises her point by highlighting a collection of Egyptian filters from the Fatimid dynasty of the 10th century which fit in the top of a jug. Simple, useful but lovingly decorated — a little elephant on one, some writing on another which exhorts: “Be generous and you will be rewarded.”

There is something both moving and depressing about the artefacts that are on show. Moving because they reflect the creativity of so many unknown craftsmen, depressing because so many of the cities and ports where they plied their trade have today become synonymous with destruction and blinkered ideology.

Take Herat in Afghanistan, caught up in recent years in the interminable struggles with the Taliban. In the 12th century, the city led the way in metalwork, using gold, copper and silver to bring a brilliance to their work. A ewer densely decorated with lions and parakeets, human heads and the planets of the zodiac, also has a poem in praise of its own beauty — as well it might.

From Raqqa in Syria, devastated during the civil war, a ceramic and glass dish in blues, greens and browns from late 12th to early 13th century, from Mosul, similarly torn apart in years of violence, a shimmering ewer in brass with slivers of silver and copper from 1232. Known as the Blacas Ewer after its owner it was made by a craftsman from an important Mosul family, it shows detailed scenes of courtly life, rulers on their thrones, musicians, huntsmen, a woman on the back of a camel with her servants.

This is not to say the region has not been subjected to violence before. Conquest after conquest, dynasty after dynasty such as Umayyads (661-750) in Damascus or the Abbasids in Baghdad (750 - 1258) made their mark.

The Mamluks who had come from the steppe north of the Black Sea founded an empire with a capital in Cairo which stretched from Egypt, along the coast of Arabia and up the Mediterranean to include Syria. The glassware of the period of their rule which lasted from 1250 to 1517 is exemplified by a pair of mosque lamps in gilded and enamelled glass. They are among the most beautiful on display. Designed for the governor of Hama in Syria, they are objects of rare delicacy with two symbols, a cup and an eagle with a shield and inscribed with a verse from the Quran. which reads: “God is the light of the heavens and the earth; the likeness of His light is as a niche wherein is a lamp (the lamp in a glass, the glass as it were a glittering star). A poignant contrast to Hama today, a city that has suffered unbearably in the country’s civil war.

By the mid-7th century Muslim power extended from Spain to central Asia and, as a map in the scholarly book which accompanies the project illustrates, the outermost boundaries of Islamic culture stretched across geography, time, distance, boundaries and media from Marrakesh and Vienna by way of Sudan and India to Kuala Lumpur and the shores of the East China Sea.

Workers travelled from say, Nishapur in north eastern Iran, to share their skills in the use of slip ware — a semiliquid clay — which was used for sgraffito, a form of decoration made by scratching through a surface to reveal a layer of differing colour, as well as carving and painting, while the craftsmen of Khashan, another Iranian city, introduced stone paste, a mix of ground glass and clay. To take one example: a bowl from 1187 portrays a royal figure seated on his throne surrounded by birds and flowers with courtiers and visitors in attendance. The detail of the robes of red, blue and black, some striped, the expressions of loyal obsequiousness in the faces of his subjects faces is extraordinary.

There was a constant eddy of people and information. Artisans from Mosul took their metal work skills to Egypt, pilgrims would return with new knowledge, craftsmen would take designs from each other and reinterpret them, they would discover mathematical shapes, music, dance and architecture.

They could use sophisticated equipment to guide their travels. Astrolabes decorated in gold and a globe showing the stars and constellations in brass and silver from Iran in 1275 helps to explain how a gorgeous flask, radiant in pinks, gold and blues with scenes of country life, a female harpist, could have been transported from Damascus to China (and miraculously survived 800 years without being broken).

One of the most extraordinary examples of international trade — and one of the more mysterious — is the hoard of African gold, earrings, amulets, 400 coins and gold ingots from a Marrakesh tribe made in the 17th century which was found in 1994 off the coast of the small English seaside town of Salcombe in Devon.

Even with the merciless invader from the east, Genghis Khan and his Mongol hordes, who wreaked havoc in the early 13th century, the art and the crafts continued to flourish. In fact, the Mongol overlords almost wove themselves into the culture of their conquered territory. Hand-picked craftsmen were sent to Tabriz, which became the capital, and to Samarkand with the inevitable exchange of talent and technique.

The Ilkhanids, the dynasty founded by Ghengis Khan in Iran, demanded that their camps and palaces were lavishly decorated with objects that were beautiful as well as functional and the influence from northern China, which was under their thrall, became more evident with images of peonies and dragons. A glass mosque lamp, exquisitely enamelled in red, blue and white, is decorated with lotuses.

The galleries move through the centuries and across the borders with embroidery from Turkmen, weaved out of silk cotton and human hair from the late 19th, early 20th century, textiles from Pakistan and Brunei, even Turkish shadow puppets made from camel leather from the 1970s.

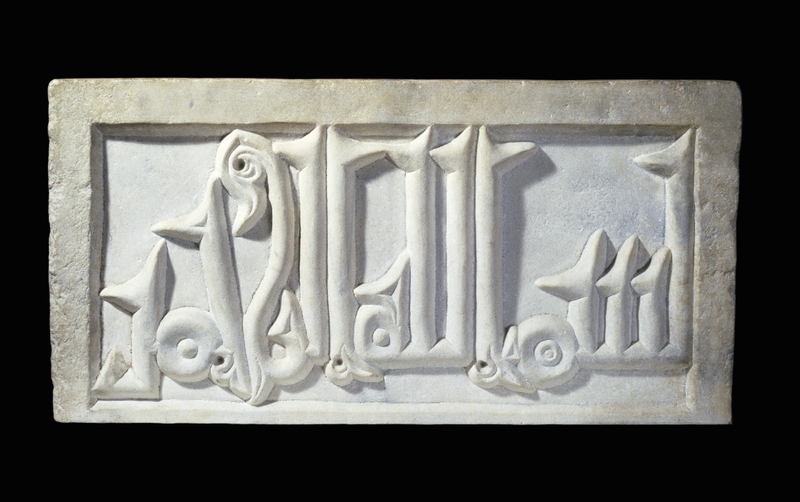

Examples of calligraphy such as a page of Persian poetry from the early 17th century and another from the Ottoman Turkey of 18th/ 19th century which reads: ‘Oh Lord, make it easy and not difficult.’

A drawing from the Mughal era in India has an angel riding a camel holding a bottle of incense, surrounded by demons and mythical figures. Part Indian, part Iranian, it demonstrates the interplay of skills and styles that characterise so much of the artefacts.

It does not ignore the contemporary. British artist Idris Khan has filled an entire wall with what appear to be great splashes of blue. Close up it is possible to decipher parts of messages or wishes in typewriter type though not one of the texts is completely decipherable.

Entitled “21 Stones”, the work by Khan, whose father is from Pakistan, has tried to convey the moment of release for a Hajj pilgrim performing the stoning of the Jamarat at Mina when pilgrims throw 21 stones at the wall which represents the devil. As he throws, he wishes away any bad feelings or thoughts.

The splash of the blue represents the emotional release of a stone hitting the wall.

It was created in the 21st century but its inspiration can be found at the beginning of the Islamic world, with the first Hajj which took place in 629.

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.