Balkh, Afghanistan: In the white dusty plains of northern Afghanistan, archaeologists are seeking to unravel the secrets of one of the oldest mosques in the world, whose structure is still standing after a thousand years of solitude.

The Nine Domes Mosque, named for the cupolas that once crowned its intricately decorated columns, glimmers with remnants of the blue lapis lazuli stones that encrusted it.

Carbon dating results in early 2017 suggests the ancient structure in Balkh province was built in the eighth century, soon after Islam swept into Central Asia — but exactly when, and who by, remains a mystery.

The very survival of this modest square of just 20 by 20 metres has beguiled experts.

“It’s a miracle it’s still standing despite time and erosion,” said Italian architect Ugo Tonietti from the University of Florence, who specialises in heritage conservation.

The mosque, which has weathered the centuries partly due to the arid climate of the region, is one of the best preserved Islamic buildings of its age in the world and is “highly valuable and highly vulnerable”, he said.

Time has washed most of the colour from its columns, but the mosque was once a dazzling spectacle.

“This is a masterpiece. You have to imagine how it looked like, fully decorated with lapis, some parts in red, it was all covered and painted: it was like a garden of paradise inside, with a sky above, the domes with white and blue decoration,” he said.

The delicate vine leaves etched onto the pillars resemble those seen at Samarra, Tonietti said, referring to the powerful ninth century Islamic capital city that ruled the Abbasid Empire extending from present day Tunisia to Pakistan.

But the mosque at Balkh could be even older, with the carbon dating and historical sources suggesting it could have been built as early as the year 794.

“This means that the mosque of the Abassid Empire has been influenced by Afghanistan, not the other way around,” said Julio Sarmiento-Bendezu, director of the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan, who is leading excavations at the site.

“This mosque is exceptional in its beauty, conservation, decoration and the knowledge it holds,” he said.

But Noh Gonbad, its Persian name, was only rediscovered by chance.

In the late 1960s, an American archaeologist travelling in the region asked local people to take her to a mosque destroyed by Genghis Khan, the Mongol emperor who rampaged across the region in the early 13th century.

Villagers led her to this lonely, half-buried temple some 20 kilometres west of Mazar-i-Sharif.

Once found, however, the building languished once again as war was unleashed on Afghanistan, enveloping the country in decades of bloodshed, and it was not until 2006 that excavations began on the site.

“We thought at first that it was an isolated monument, but as we went on we saw that it was stuck to other older structures,” said Sarmiento-Bendezu.

“At the end of the eighth century, the Buddhist world was in torment in the region. No doubt it was built on the remains of a monastery.”

In July archaeologists unearthed the base of the pillars, at a depth of 1.5 metres, but surveys suggest even deeper remnants.

“This is a window open to the ancient period, here we can find the base of the next culture to come,” said Arash Boostani, an Iranian architect and engineer from the University of Tehran, who was commissioned by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) to work on the site.

A specialist in conserving historical monuments, he said that some of the flower designs on the mosque are pre-Islamic and have been absorbed from local culture.

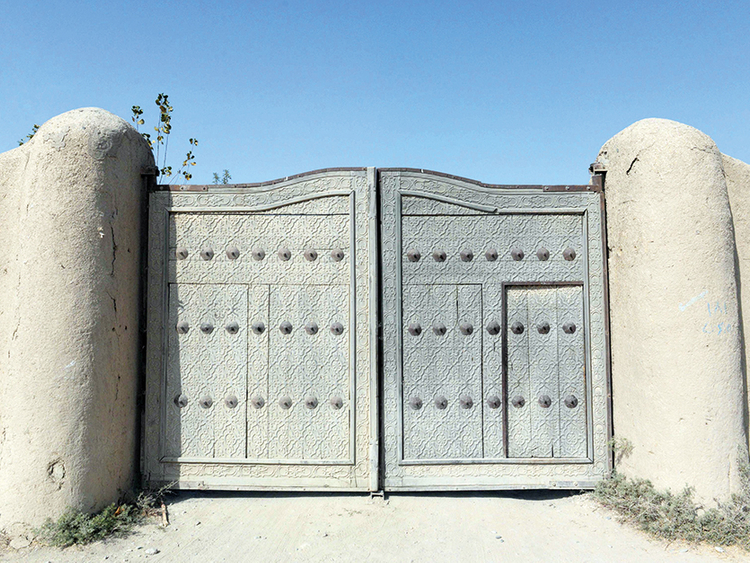

The building, which has been protected from the elements by a metal roof, remains vulnerable because its brick and patchwork structure is susceptible to erosion.

Noh Gonbad’s domes were toppled soon after the mosque was built and have lain at the site during the centuries since.

“With the earthquake in 819 most of the mosque collapsed,” Boostani said.

Another earthquake a hundred years later hit the outer walls and most of the 15 arches.

The experts stretched fibreglass nets to support the two main, deeply cracked arches, and injected cement — without altering the gypsum decorations.

“The place has always been occupied,” Sarmiento-Bendezu said. “Monastery and then mosque, abandoned and squatted in — we found fireplaces.

“Pieces of the domes, however heavy, were transported and used to cover nearby tombs: why give yourself this burden if the building did not have strong symbolic value?”

Noh Gonbad remains a place of pilgrimage: the women come to gather on Friday and weep over the tomb of an obscure saint, Hadji Pyada, the walking pilgrim, buried there in the 15th century.

“Like all excavations, those of the Nine Domes Mosque pose more questions than they answer,” says the archaeologist.