Short-lived abstraction

The virile optimism of Vorticism exploded on the art scene in 1914, only to be crushed by the horrors of war

Harder, faster, fiercer, louder: Jacob Epstein's The Rock Drill confronts you at the door, muscles flexed, thighs splayed, pumping away with his tool. Half-man, half-anthropod and precursor to a thousand Hollywood androids, Epstein's figure is a shocking creature.

He has terrible force of personality. And he is the most devastating creation in this show, a sculpture from 1913 that seems to summarise all that Vorticism stood for with its ambition for machine-age dynamism and shattering new forms. The Rock Drill ought to be the ideal host, the perfect symbol for the movement and the show. Except that Epstein was never a paid-up vorticist.

In the long march through Modernism, Vorticism is the quickest of steps. It flares up in 1914, peaks briefly in 1915 and sputters out towards the end of the First World War. There are only two shows. There are only two issues of its in-house journal, Blast. There may be only one full-time vorticist.

"Vorticism," declared Wyndham Lewis in the 1950s, "was what I, personally, did, and said, at a certain period."

The assertion may have infuriated the surviving members of the group but it is not without its merit when you consider the diversity of their gifts, from the painter David Bomberg to the French sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, compared to Lewis' single-mindedness as ringleader, recruiting sergeant, megaphone, exemplar and theorist of England's only home-grown avant-garde movement.

Lewis belongs to the first generation of Europe's non-representational artists. His drawings are incisive, satirical, on the edge of abstraction. His paintings from this phase — angular, syncopated, explosive — are even better, which is some claim, given that scarcely any survive.

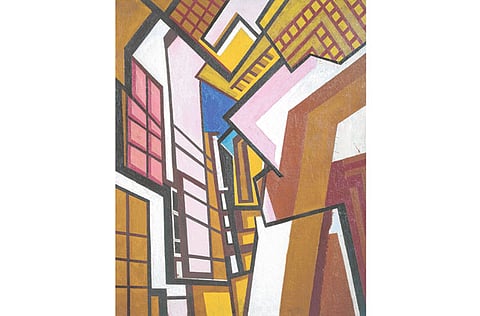

In the 1912 illustrations for Timon of Athens, he begins to abandon depth for a flat pageant of forms that jostle like the elements of some unsolved puzzle. By 1915, in his enormous painting The Crowd, he shows quasi-cubist figures scattered in a system of grids that seems to prefigure the pinball machine. Workshop (1914-15) is a marvellous concatenation of geometric planes, in coruscating pinks and hot mustards, that almost resolve into windows, ladders, stacks and shelves, by day and yet also, as it seems, by night. It turns architecture inside out. And seeing it in Tate Britain's survey, surrounded by fading issues of Blast, old catalogues and invitations, typed manifestos and handwritten declarations of solidarity or hatred — period pieces of English art history from 100 years ago — it looks more modern than ever. With its graphic zip and register, Workshop conjures pop art half a century in advance. There are other masterpieces in this show, but not many. Tate Britain has David Bomberg's painting The Mud Bath, with its interplay of bent, reclining and zigzagging forms packed into a scarlet tank. It has Gaudier-Brzeska's Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound, on loan from the National Gallery in Washington, biting its mucklestone lip.

Nobody visiting this show could fail to spot the influence of abroad in almost every work. The Dancers, Les Demoiselles: Wyndham Lewis's chorus line wends its way directly out of Picasso. Roger Fry had mounted his celebrated exhibition, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, back in 1910, the same year Marinetti delivered his futurist lectures in London.

The trick with this show is to try and remain indifferent to the obvious strains of Cubism and Futurism that appear wherever you look. It is not hard, for instance, to deduce local figurative forms in all this accordion-pleated abstraction — piano keys and nightclubs, people and performers, London alleys and even the back-to-back terraces of northern mining towns. Lewis saw that Cubism, for instance, could be more than a highly advanced visual language. It could be made to speak of life itself, with all thronging motion, humanity, incident.

One of the strongest works here is his wonderfully acute Architect With Green Tie (1909), which skewers the self-importance of a particular man while sending up the profession's characteristic fondness for that calculated spot of colour. The work isn't abstract at all, in fact; it's one of Lewis's best caricatures. But it also predates Vorticism, exposing an unusual dilemma for the curators of this show, which originated in North Carolina. Vorticism is such a brief movement and so little of the art survives (a huge tranche of it, belonging to the American collector John Quinn, vanished long ago) that it is quite a feat to assemble anything representative.

The exhibition attempts to counter the problem by including a good many fellow-travellers, recreating both the original vorticist shows and displaying the issues of Blast, wonderful woodcuts and wild demagoguery, along with testaments of war, imaginary and real.

The Vorticists, Manifesto for a Modern World is on at Tate Britain, London, until September 4.