Ghayathi at first glance seems to be a sleepy town with little else going for it except oil - Adnoc has a refinery in nearby Ruwais. But a visit to the small single-storey houses that dot the area show there's a lot going on behind the scenes.

For one, it is a settlement of the Al Mansouri, one of the Bedouin tribes famous for their weaving techniques. In the past couple of years, there has been a gradual revival of the art of weaving among these inhabitants thanks to the Sougha Initiative of the Khalifa Fund for Enterprise Development. The Sougha Initiative envisages the development of entrepreneurial skills, while encouraging female artisans to reconnect with their art and craft.

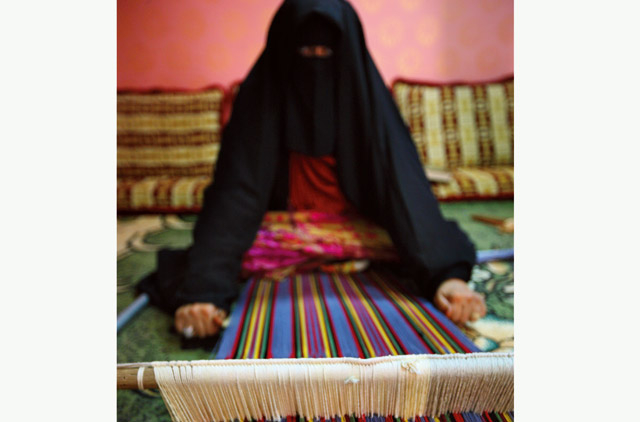

"Every woman in Ghayathi can weave, and almost every household has a loom on which you can see material in various stages of being woven," says Leila Ben Gacem, manager, Entrepreneurship Development Department, at the Khalifa Fund.

From the boardroom to grass roots

We are around 360km from Abu Dhabi in the western region and the sun is showing off its seasonal might, but the diminutive Leila is oblivious to its heat as she takes us from house to house pointing out the various handicrafts the women of Ghayathi have made. These will be soon handed over to her to be marketed in the cities across the country.

A trained biomedical engineer who started her own small business "because I wanted to focus on my passion, which is working with microbusinesses and helping them expand", Leila's stint with a multinational corporation taught her how to globalise businesses.

And now, "I want to do it for my own people."

And so we are on a tour of Ghayathi: Leila is looking at the work of the members, totalling the money they have to be paid for goods delivered and encouraging them to keep at their looms and sewing machines.

We soon join Najla and Afra Syed Al Mansouri, sisters who are married to two brothers of the Al Mansouri family. Afra is visiting Najla on the day we are with them. "They were the first weavers in Ghayathi who joined the Sougha Initiative and are among the most productive," says Leila as she plays with Najla's grandchildren. As if on cue, Najla asks her: "Do you have any money for me today?"

Najla has a loom - aluminium pipes fitted together to form a rudimentary frame, with empty tins to prop up the thread and cloth at either end - in her room where she works whenever she's free from her domestic duties. With many children and grandchildren, she finds time hard to come by, but works on the lavender-coloured cloth that she will fashion into mobile phone covers whenever she can. She and her sister are so devoted to the craft and have persuaded their relatives and friends to pitch in with the initiative. Now there are 38 women who sell their products through the Sougha Initiative.

"I feel there is a lot of human potential for microbusinesses in the UAE," says Leila. "It can encompass many sectors. The Khalifa Fund started with the handicrafts because we believe there is a strong need to revive heritage and find a place for local crafts in the very competitive UAE market. In the rural areas education is increasing, but not the job opportunities. We can help them develop their traditional skills and show them how to market their products, develop it into a potential home-based business."

The initial thrust of focusing the initiative on handicrafts came from one of the Khalifa Fund's priorities to revive traditions through development of entrepreneurial and technical skills, and the creation of opportunities for such artisans. "Our aim is to revive the heritage and preserve the Emirati identity. This was a priority for late Shaikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan, and his vision continues even today through such initiatives," says Leila.

When the Sougha Initiative was launched, the Khalifa Fund's mandate was Abu Dhabi. But it was extended to the rest of the emirates last month. "We now cover the whole of the UAE," smiles Leila proudly. Recently she was in Fujairah, holding a workshop for members of the Fujairah Welfare Association (FWA) on the intricacies of running a successful business. The 15 women who turned up were impressed with the "little lady who spoke big things."

Fatima Rashid is a members of the FWA. She says, "Such programmes are always helpful. My mother makes these small purses from palm leaves - a craft we lost when we stopped weaving them into baskets to store dates in. My mother learnt it from her mother. We have date farms and in those days they used to make baskets to store dates. My mother got the idea of weaving these smaller items after someone gave her a similar purse made in Indonesia. She liked it and tried her hand at it, with an Emirati slant. She's been doing it for two years. It's selling well, not only in Fujairah, but also in Dubai. The small purse takes two days to make and sells for Dh20."

Faiza Mohammad has been making and selling women's accessories, and catering for weddings for the past 18 years. "I applied to the FWA, who saw my work and the potential in my catering, then signed me up for this workshop," she says. "I am looking for ways to expand my businesses, that's why I am here."

Shaikha Habid and Fatima Ali are friends who jointly run a small perfume business. "We have been doing this for the past four years," says Fatima. "This training session has taught us a lot. We met others like us and that has given us confidence. We have a lot of ideas, but the lack of resources limits our growth. We are now thinking of diversifying the products and making it more commercial."

Helping people improve their lives

Alia Obaid Humaidi, microbusiness evaluator at the FWA, sees a lot of potential for the Sougha Initiative. "Our welfare project began in 2004 with two families, now there are 118. We even have three men among them. The projects include handicrafts, beauticians and chefs working from home, even financing of taxis. We give interest-free loans for them to start businesses. The amount depends on the projects. It can range from Dh3,000 to Dh100,000. The association was established 25 years ago and since then we have seen a major difference in the lives of our members. Many come to us not for money but technical support."

"We conducted a pilot project as part of the Sougha Initiative last June that has been very successful," says Leila. "We held three workshops for women skilled in crafts, at the end of which we converted the skills into businesses. We are getting orders now, which we pass on to the members as their businesses expand. The idea is to give them the tools to develop into a more evolved business."

Local handicrafts are improved upon so that the artisans can market the products. "We are providing technical support for these businesses but we are also hoping that our cooperation will grow so that we can strengthen not only them, but also the economy through them. The idea is to make them self-sufficient."

The local craft in Fujairah is khoos, weaving of dried palm leaves into baskets for storing dates, says Alia. "Now they are trying to modernise their craft, making purses, bags and other products that are in demand."

Leila adds, "There were other crafts connected with fishing that have fallen into disuse, but we are hoping to revive them. The skill is still there, but has become rusty as it was not needed anymore." Now, with the backing of the Khalifa Fund, local crafts seem set for a revival.

"In this region the handicrafts mostly revolve around the Bedouin crafts - weaving and basket making. Now with the expansion of the initiative I think it's going to get a lot more busy as it encompasses other crafts which we have not investigated yet."

Knowledge and capacity building

The Khalifa Fund's stand is that there is a lot of human potential, and skills need to be analysed to identify how gaps can be bridged. "Technical know-how is required to hone their craft, and fill the socio-cultural gaps in understanding the market requirements," explains Leila.

Based on these requirements, Leila and the team at the Khalifa Fund have developed workshops for participants that aim to convert their skills into businesses. "In the beginning it was very hard to convince people that such products would sell, but now I think we have come to a stage where we have created a market demand and there are more and more people who want to revive their skills," she says.

One of the most emphatic signs that the initiative is hitting its target is that the average age of artisans involved is going down. Which means that because of the economic benefit it has created, the younger generations are becoming interested and getting involved.

"In fact, the benefit is not just economic, it is also becoming creative and trendy in a way that the younger people can accept it," says Leila. "When we started the initiative we had women in their 60s and 70s working with us. Now it is down to the 40s. I think that is a sign that the initiative is sustainable, Inshallah!"

Home-based businesses are an attractive option for women. "In fact, we developed the Sougha Initiative in a way that doesn't demand any social sacrifice for the artisans," says Leila. "Even the families are satisfied. She's there right at home, tending to her duties while making money. I think there is a lot of potential in microfinance in this region because it is socially acceptable."

Leila thinks young males will be attracted to start microbusinesses in the future. "I hope that through our work we will make it more attractive to men to take up such initiatives.

"In most cases women who run these handicraft businesses are not the prime supporters of their families. For men, it could be different as they have to provide for their families. We hope to help men start their own home-based businesses that could support their families too."

Aliya agrees. "Some men are also getting assistance from us to start their businesses, so I don't see why not."

The Al Mansouri tribe

Bkhita Abdullah Al Mansouri holds up the beautifully designed red cloth she's woven on her loom. As Leila compliments her on her work, Bkhita points to a sign in the design that looks like an inverted ‘V' balancing a straight line on its edge. "Do you know what this is?" she asks, her dark eyes sparkling with mischief, behind her mask. "It's the sign of the Al Mansouri tribe!' she announces triumphantly.

The Al Mansouri tribe - that traces its origins back to the times when Bedouins wandered the lands - apparently used the symbol to brand their animals and had it on all their belongings. "I learnt this from my mother and use it in most of my work," says Bkhita proudly. Her one regret? No one else in the tribe uses the symbol any more. "I am trying to keep it alive," she says. "Even my children don't know why I use it. But now some of my daughters are showing interest in my work. Perhaps they will carry it forward."

By the way …

Leila Ben Gacem says she tries to go out to the field and investigate what skills there are among potential businesspeople that can be nurtured. She says, "We also hold a lot of awareness sessions and workshops through which we try to educate them on self-employment, and build trust in our initiatives as many of them would rather wait for a government job. We take them through the paces of building a successful business."

For more information, http://www.khalifafund.gov.ae /Tel: 02 696 0000 Email: sougha@khalifafund.gov.ae