Pakistan’s happy moments

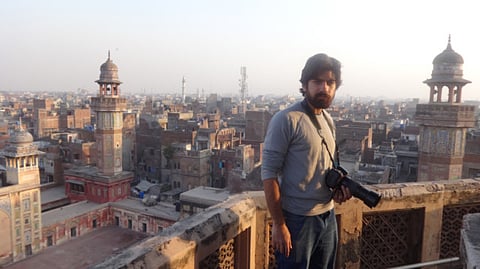

Photographer Mobeen Ansari refuses to toe the line of the media that doesn’t see anything but violence

Mobeen Ansari is a talented young photojournalist from Pakistan. He tries to capture a positive side of the country often neglected by a media more interested in political tensions and the frequent bomb explosions. “I do not want to photograph that because Pakistan has already taken too much beating for that,” Ansari tells Weekend Review. “It is too easy to get these negative stories. All you have to do is pass by and something or the other happens. Granted, these things are happening, it is real. You can’t hide from it. But then people have to know something else. People have to know the amazing success stories that are coming out of here. There is so much that Pakistan has to offer. ”

The Islamabad-based Ansari has travelled the length and breadth of Pakistan, from the mountainous northern areas to deserts and shores of Sindh in the south.

I met him one afternoon while he was visiting Lahore. I was curious to see first-hand how Ansari operates, so he took me to Androon Shehr (old city) — a part of the city he has photographed on numerous occasions. Because of family ties Ansari has been visiting Lahore since an early age and he also spent some of his university years here: Having graduated from National College of Arts (NCA) in Rawalpindi, Ansari went on to do his masters at NCA’s Lahore branch.

“NCA is located in a very old area of Mall Road,” he says, during our drive to old Lahore. “So it gave me an opportunity to photograph old places. In the evening I would go into Androon Shehr and start taking pictures. My aunt introduced me to the whole cycle of waking up before Fajr and going to the masjid. She would show me all the old mosques, alleys and what the people over there would cook. We would get there before sunrise when it was completely foggy. I really liked that. So I started doing that with her every time I was in Lahore. Now she is married and living in the United States, so I do that on my own, or with my friends.”

Lighting technique

Having a background in arts has been useful. “When I take photos, I make sure it looks like a painting. For example, if I look at old-style paintings such as Rembrandt, I adopt their lighting technique. That’s why I love ‘androon’ Lahore, because especially if you go there early morning, you get a lot of good lighting. There is a lot of history. It is like going back in time, like painting a picture. Because when you go deep into the alleys, when you see the old men, the characters down there, it is almost like they are out of a painting.”

Weaving through a lot of traffic we finally reached old Lahore, and entered on foot through Delhi Gate — one of 13 gates built during the Mogul era. Pedestrians rule the streets as there aren’t cars around, except some rickshaws or motorbikes. As we walk deeper inside I spot a man built like a pehlwan (traditional wrestler) and suggest we approach him for a photo. “I know he won’t allow photography,” Ansari says. “He is worried, and he has got a heart problem.” How does he know? “Because he is walking very carefully.”

Ansari specialises in portraits. In fact he has a new book out this month, “Dharkan – The Heartbeat of a Nation”, a collection of portraits and stories of 98 well-known, inspiring Pakistanis such as cricketer Shahid Afridi, Sufi singer Abida Parveen and famous comedian Bushra Ansari. He tells me about photographing the humanitarian worker Abdul Sattar Edhi.

Ansari was told not to make an appointment but just go to Kharadar, the place where Edhi was, and ask for a photo shoot. “Edhi was just sitting there. I introduced myself, and I told him about my book, why I wanted to do it. He was very weak, very old, and still he said, ‘OK, let’s do this.’ I think Abdul Sattar Edhi is the best Pakistani who has ever lived and I met him two times.”

Another interesting photo shoot was of politician Imran Khan at his Islamabad residence. “He is very camera-shy,” Ansari says. “I actually photographed him for a magazine, but wanted to put him in the book as well, because my entire generation grew up wanting to be like him.”

He had first met Khan as a young child in 1993. “He came to my school Beacon House when his hospital was being built,” Ansari recalls. “He was collecting funds from schools. That was the first time I met him. I gave him flowers.”

The photo shoot took place years later. “I was installing the lights and other equipment, and he was telling me to hurry. And I thought he was not in the mood for the shoot since he is camera-shy. But the actual truth was, he didn’t have a generator, and the lights were about to go.”

As we proceed further down the streets of old Lahore, the throbbing veins of this living, breathing city, we soon find ourselves standing in front of the towering structure of the Wazir Khan mosque, which is almost 400 years old. It was built during the reign of the Mogul emperor Shah Jahan.

Ansari is supported in his work by acclaimed US-based Pakistani novelist Bapsi Sidhwa, who played a major role in his American book-launch a few months ago. “Parsis have done a lot for Pakistan and Bapsi is one of them. That is why I wanted to photograph her. She signed the book — ‘to my adopted son’.” The book launch in US went well. “The copies sold out within 10 minutes. You know the actress Gates McFadden? [The doctor in “Star Trek: The Next Generation”] She was the first person to buy my book. She just noticed me on Twitter, saw my work, and asked if I have some published work. The entire conversation took place on Twitter. It was very inspiring because she is one of my favourite actresses.”

One particularly photogenic subject was Sufi singer Saeen Zahoor. “The first time I photographed him was way before the project began,” he says. “It was for a magazine, in Lahore. It was completely dark and I had to bring my own light. If you’ve listened to his voice, Saeen Zahoor feels like such a larger-than-life figure. I was very intimidated to be photographing him. But during the course of the shoot, he knew exactly what to do. He is like the ideal person you would like to photograph — from his eyes, to his turban, the beard, his character, his dress. He is one person I never get tired of photographing.” He had the opportunity to photograph him again for the book at his home in Lahore.

Ansari already knows what his next book is going to be on: the minorities of Pakistan.

As we enter the mosque, we take off our shoes. The doors to the minarets are locked but Ansari speaks to his contacts and we are let in. As we enter through the door, a man locks us up inside and asks us to ring him when we are done. We climb the long flight of steps.

The view from the top truly captures the spirit of old Lahore. As I look down from one side of the balustrade, I spot the huge courtyard of the mosque. There are pigeons flying and some worshippers walking around or praying on mats. I look around at the many houses and buildings surrounding the mosque. Sometimes a face peeps through a window, or a woman appears on a balcony. Some men on a rooftop are dyeing clothes. Ansari is busy clicking away with his camera. “I want to get that old-painting-like feel,” he says.

When he was about three weeks old Ansari suffered a severe meningitis attack due to which he lost a lot of his sense of smell and hearing. In noisy situations he finds it difficult to interact. “I have been an introvert all my life,” he says.

Then, a few years ago at a wedding he lost his hearing almost completely in one ear due to the blaring loudspeakers. Ansari now uses a hearing aid and hears mostly out of his left ear. “Unfortunately it is my weaker ear. But my life has become much more interesting since I started hearing from one ear because actually it’s made me put more effort in understanding things. That was my final year in college. Everything became much more challenging. Because when you listen with one ear, you have to filter out the background noise. You have to filter out everything. You have to filter out the person you are talking to. When I speak to somebody, I mostly understand by body language or by lip-reading. So I apply that to my photography. I observe people. I can see, I can tell what they are thinking. You know from their hand motions, how they are sitting, how they are looking. So I use that in my portraits, to try and tell and get an insight into who they are.”

One of the most touching photographs for Ansari is of the actress Iman Ali, who suffers from multiple sclerosis. It took Ansari about four months to contact her. “One day, finally, she picked up the phone. I said I wanted to photograph her — not just because she was a successful model and actor, but because she had turned a weakness into strength. Despite all that, she was still working. She was creating awareness about multiple sclerosis. She was still on billboards, she was going to be in some more films. So she said, ‘OK, come over, and we’ll talk about it’. When I spoke to her, she had tears in her eyes because we had started talking about what we had in common. She started crying and she asked me to take pictures.”

Back atop the minaret, Ansari’s eyes are busy scanning the different directions as his camera clicks away. “What I like about here is people are relatively more liberal. Have you noticed?” Does he mean they don’t care about people taking photographs? “Not only that. For example if a woman comes here, even the imam lets her inside the prayer area to interact. That is a very good mindset.”

When it is time for us to leave, “the lights are already switched on here,” Ansari says. “It’s the sunset but people here don’t see that. Over here they only see darkness. You find an interesting play of lights. I will take one last shot and then we will go into the streets.”

Soon we are climbing down the stairs, ringing the caretaker on his mobile to let us out, and back on the street. We come across an alley which Ansari decides to explore. It leads us to another narrower passage and I see some women standing at their doors looking out. It appears to be the kind of mahalla (a traditional neighbourhood) where everyone knows each other. “Normally if this was Islamabad or Rawalpindi, people would be staring at you,” Ansari says, “But over here they are all cool. That is the kind of mindset a Pakistani photographer needs to get around.”

Syed Hamad Ali is a writer based in London.