A mastery of arts

The Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, a rich repository of the earliest manuscripts and art objects of the Islamic world, leaves even Muslim visitors in awe

"There is no God but Allah, and Mohammad is the messenger of Allah."

In neat gold calligraphy, the words of "La Elaha Illa Allah" are inscribed in the ceiling recess, bright spotlights highlighting the walkways through this representation of the Five Pillars of Islam.

But this is no mosque — this is a library in the heart of what was the most Catholic nation in Europe.

Outside, just metres away, Vikings once grounded their longboats on the shores of Dubh Linn — the black pool — the muddy waters that gave Dublin its name and helped build a permanent settlement 12 centuries ago. While the Scandinavian warriors were busy marauding coastal communities around the British Isles, Islamic scholars in the Middle East were busy writing down the secrets of science, medicine, mathematics and religion.

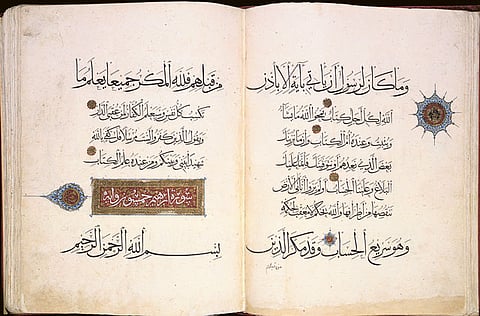

Today the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin Castle, the historic centre of Ireland's capital, houses the only permanent exhibition in the western hemisphere devoted to the beliefs of Islam. That collection includes more that 260 illuminated copies of the Quran and manuscript fragments dating from the 9th to the 19th centuries.

One of the gems of the Islamic Collection is a Quran copied in Baghdad in AD1001 by Ibn Al Bawwab.

Also known as Abu Al Hassan or Ali Ibn Hilal, Ibn Al Bawwab was a celebrated Islamic calligrapher and artist who, at the turn of the 1st millennium, gave Arabic writing a new flow and beauty, having previously mastered a number of styles and developed a unified sense of proportion for each character. He is thought to have completed 64 separate copies of the Quran, of which only the Chester Beatty version survives.

In addition, the collection contains more than 2,600 non-Quranic Arabic manuscripts dating back to the 8th century.

It is not surprising, then, that the library remains to scholars the most important source of early Islam outside the Arab world. Depending on how manuscript pages and fragments are counted, the library's total collection could comprise 100,000 artefacts — with about 1,000 items on display at any point of time.

The whereabouts of the huge proportion of priceless artefacts not on display are a closely guarded secret.

"Although not as large as the collections in, say, the British Library or the Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris, the Chester Beatty collection of Islamic manuscripts is considered one of the most important such collections outside the Middle East," says Dr Elaine Wright, the curator of the Islamic Collections at the library. "This is because of the high quality of the material — Chester Beatty was noted for having a very fine eye, and he made it a point to purchase only the finest material — and because the Arabic collection includes a large number of unique copies of texts. No other copies are known to have survived other than those that are here in the Chester Beatty Library. The Quran collection — some 260 manuscripts — is especially renowned, as is the Mogul collection. However, the Persian and the Turkish works are also very important."

The Islamic Collection is made up of more than 6,000 individual items, mainly manuscripts and single-page paintings and calligraphies, Wright notes. This includes more than 260 complete and fragmentary versions of the Quran.

A New Yorker by birth, Alfred Chester Beatty made a vast fortune from copper mining. An avid collector from an early age, he developed a keen eye for fine manuscripts and used a large network of buying agents from around the world to amass an unrivalled collection of manuscripts, books, scrolls and objects d'art. He moved to Britain, but, disillusioned with postwar politics, he finally settled in Ireland, becoming an honorary Irish citizen. He died in 1969.

The Western treasures of the Chester Beatty Library include some of the earliest papyrus sources for the Bible and a great collection of Manichaean texts. Beatty's Biblical Papyri, dating from the 2nd to the 4th centuries, consist of the earliest-known copies of the four gospels and the Acts of the Apostles, the letters of St Paul, the Book of Revelation and various early Old Testament fragments.

The library's Armenian and Western European manuscripts from medieval, Renaissance and modern times, along with prints and early books and bindings, complete a priceless collection of the arts of manuscript production and printing from many cultures and periods.

Beatty's collection also includes one volume of the manuscript of the Sirat-i Nabi (The Life of the Prophet), produced for the Ottoman Sultan Murad III in 1594 and 1595. The work consisted of six volumes, of which one is lost, one is in the Chester Beatty Library, one in New York and the other three in Istanbul.

The manuscript in the Chester Beatty collection is unusual in that it is an illustrated life of the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH), with the original six-volume manuscript estimated to have contained more than 800 illustrations.

In the works, the Prophet is shown with his face fully veiled, wearing a green robe and with either his head or his whole body surrounded by a flaming halo.

"Most of our visitors are non-Muslims, but for Muslims it is an opportunity to see some of the finest Islamic manuscripts ever produced," Dr Wright says. "Not only the non-Muslim visitors but even the Muslim visitors are impressed by the quality of the material. Most of them are especially pleased to see so many high-quality versions of the Quran."

The East Asian Collection includes a series of albums and scrolls from China, the largest collection of jade books from the Imperial Court outside China and a large collection of textiles and decorative objects. The Japanese holdings in the library's archives include many superb painted scrolls from the 17th and the 18th centuries. It also includes woodblock prints by Hiroshige and Hokusai, and various decorative art objects.

While the library had the honour of being called the European Museum of the Year in 2002, it remains very much a working library where academic research is carried out.

"Scholars, both Muslim and non-Muslim, from around the world, work on all aspects of Islamic manuscripts, studying illustrations and illuminations, book structures, calligraphy, etc, and, of course, the texts," Dr Wright says. "As for the library itself, the Chester Beatty Library collection, and in particular the Arabic Collection, is an important source of information on the history and culture of the Islamic world. Students and scholars from around the world visit the library every year to refer to its manuscripts."

At present, researchers at the library are compiling a new comprehensive catalogue of the Arabic Collection. It is painstaking work on the more than 2,600 priceless manuscripts, and the research will supplement an eight-volume handlist produced by A.J. Arberry in the 1950s and 1960s.

Various international scholars are contributing to this project, which will take many years to complete. The library has also, in the past few years, published two books authored by Dr Wright on its Islamic Collection.

Who was Sir Alfred Chester Beatty?

Sir Alfred Chester Beatty was a US-born mining magnate and millionaire, often called the "King of Copper".

He was born in 1875 in New York and soon developed a keen interest in minerals, going on to study geology, graduating from Columbia University in Mining Engineering.

Named after a distant relative, he disliked his name and always signed his name as "A. Chester Beatty". He made a fortune discovering copper in Cripple Creek, Colorado, and later discovered huge deposits of the metal in Zimbabwe — then known as Rhodesia — and Zambia.

In 1900, he married Grace Madeline Rickard, and the couple had two children. However, in 1911, Rickard died of typhoid. Suffering from ill health himself, Beatty left the busy world of mining in the US and founded a new consultancy in London. In May 1912 he bought Baroda House at Kensington Palace Gardens, London, and soon after married Edith Dunn of New York.

A collector of minerals, Chinese snuff bottles and stamps since childhood, Beatty began to collect more widely now, buying European and Islamic manuscripts. His interests found a new direction when, in 1914, he and Edith Dunn visited Egypt and bought some decorated copies of the Quran from the bazaars. The dry climate suited Beatty and he bought a house near Cairo, where he was to spend many winters.

A journey to Asia in 1917 added Japanese and Chinese paintings to his interests. His eye was drawn to richly illustrated material, fine bindings and beautiful calligraphy, but he was also deeply committed to preserving texts for their historical value.

Beatty made a significant contribution to supplies of strategic raw materials for the Allies during the Second World War, for which he was later knighted. But he soon became disillusioned with postwar politics in Britain, and in 1950 decided to move to Ireland.

There, in 1954, he built the Chester Beatty Library to house his art collection. Soon after, in 1957, he became Ireland's first honorary citizen.

On his death in 1968, he was accorded a state funeral — one of the few private citizens in Irish history to receive the honour. He is buried in Dublin.

A rare collection of Islamic seals

Dublin's Chester Beatty Library has launched an Islamic seals database, providing an interactive collection of seal impressions found in the manuscripts of its Islamic Collection.

Throughout the centuries, each time a manuscript passed to a new owner, the individual — whether a prince, a sultan or one of a more humble origin — could impress his personal seal on one of the opening or closing pages of the manuscript, leaving a historical record of ownership.

- Every seal usually carries the name of owner and the date of acquisition.

- Mohammad Bin Ahmad Bin Abdullah Al Qodsi Al Salahi, dated 7 Rehab 658 (June 18, 1260)

- Al Haji Hassan, dated 21 Rajab 1136 (April 15, 1724)

- Mohammad Bin Abdullah Bin Mohammad Abu Al Baqi Al Subki Al Shaf'ei, dated 10 Dhulqada 745 (April 24, 1345)

- Mahmoud Bin Ebrahim Al Shahruzuri, dated Rabi II 570 (November 1174)

- Esmail Bin Mohammad Bin Bardis Bin Nasr Bin Bardis Bin Raslan Al Bali, dated 16 Rabin I 780 (July 13, 1378)