Sketches of an occupied city

Palestinian artist Shehab Kawasmi brings Jerusalem alive in his intricate and carefully-crafted pencil works

Many years ago, on my arrival in occupied Jerusalem, I was gifted with a collection of pencil-drawn prints depicting iconic historical and religious landmarks, some alive with people, of the Old City, which I have treasured. They have inspired my walks to search for the beauty and mystery of those scenes. And, after all this time, I meet the artist who painstakingly drew them.

Shehab Kawasmi welcomes me into his office-cum-studio in Wadi Al Joz, an eastern Jerusalem suburb, close to the walls of the Old City. I am touched by his warmth and humbleness as I tell him of my pleasure at finally meeting the artist whose works adorn the wall of my office. He smiles and acknowledges the compliment gracefully.

“I was born in Bab Arsilsila in the Old City and it means a lot to me,” Kawasmi tells Weekend Review, recounting the beginning of his artistic journey. “In the beginning I was tutored by art Professor Shibli Karman and later by Professor Ibrahim Ibeid. In 1977, I enrolled at the Artist’s House in Jerusalem and a year later, I went to Austria and France on a scholarship. And only after my return, I began to seriously draw. In 1984, I held my first exhibition at the YMCA in East Jerusalem and my second exhibition was at the Royal Cultural Centre in Amman. Since then I have participated in exhibitions in many Palestinian, European, Canadian and Japanese cities.”

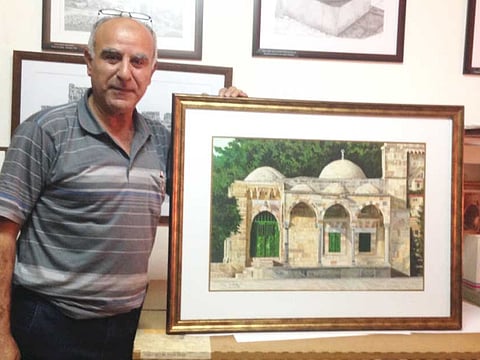

Shehab Kawasmi, Minber Burhan Eddin

So why pencils?

“I began on the project which has now been put together in a book in English and Arabic, and using pencils to depict the past in black and white was the best way to do it,” he says. “My art covers the Ottoman, Jordanian and British periods but I stopped drawing pictures of the Old City since the occupation in 1967, as I like to draw Quds (occupied Jerusalem) when it was free.”

“I went back 100 years. I found out that everything in Jerusalem was beautiful then — the streets and alleys, the neighbourhoods and the quarters, the domes and the reclining walls, the old paths and windows, even the peddlers and the craftsmen and those who had been here and are now gone. I decided to look for them. I wanted to narrate the past and the originality of the Old City, and my first drawing was of Bab Arsilsila where I was born, and hard work has completed this book, with God’s blessing and grace.”

Kawasmi has published several books that contain his works. With Kam Yama Kan (Once Upon a Time) he has realised his long-time dream of outlining the history of Jerusalem in a one-volume collection of 100 of his drawings that depict the Old City as it looked 100 years ago.

“My first drawing was in 1984, the last one in 2016 and it took me 32 years to complete 100 pictures. The resources for my drawings came from old photographs taken by Armenian families living in the Old City. I am passionate about my work and I believe in attention to detail,”he says.

Kawasmi’s drawings may seem reminiscent of Orientalist paintings in which foreign visitors and artists set about to depict the history of Jerusalem from their romanticised perspective. However, Kawasmi’s works reveal its Arab origin and identity, and they are impressive for their attention to detail and for his ability to use shades of graduation to produce an effect that has been described as similar to a musical mosaic. Artistic angles are deliberately selected to highlight the holy sites that embody the Old City’s Arab spirit, presenting the viewer with integrated artistic works that draw their beauty from the Old City’s glamour and archive the civilisation of a people who refuse to be eradicated, embedding them in human memory.

Kawasmi also manages an advertising and printing company that produces Mishwar, a monthly cultural magazine of which he points out the current issue is number 175.

“I produce copies of my original works and market it to a larger audience, as the originals would be too expensive for them to purchase,” he says. “Some of my originals have been sold to art collectors and I still have many with me. The big Palestinian companies regularly order my works for gifts with their logos added onto them. At the moment, I am translating the material from Kan Yama Kan into Turkish to print an Arabic/Turkish edition for Turks who are very interested in their Ottoman history. Last year I held an exhibition in Istanbul and two weeks ago I had one in Ankara.”

Any new artistic project?

“For the last 20 years, every morning I drive from my home in Beit Hanina to my office in Wadi Al Joz, park my car and then walk to Al Aqsa for the morning prayers, after which I return to work,” Kawasmi says.

This has inspired his new project, Qanadeel Al Aqsa — to draw and publish a collection of works that shall showcase 100 features of the Haram Al Sharif.

“There are 200 features on the Haram, but I have chosen 100,” Kawasmi explains. “It is going to be different from my previous project. This is going to be done in colour as it is the Haram Al Sharif now and not in the past. I have taken 50 pictures to work from and so far, I have completed 25 drawings. Maybe it will take me two years to complete them all. The book will be in Arabic, English, Turkish and French.”

In 2016, Kawasmi received the Best Palestinian Artist award conferred by Al Quds University for his works that embody Jerusalem. Kawasmi’s art manifests many contradictory sentiments that are reflected in the colours — these are drawings that purge the soul with their beauty, reminding one of the saddening state of affairs in Jerusalem today, and then between the black and white there is also the grey, as though some old volcanic ash which the artist hopes will erupt one day may purge the city and restore its shining elegance with human justice intertwined.

As I take leave of the artist, it finally dawns on me that it is the minute details that leave the viewer puzzled and confused between that place and the picture that embodies that place, which is the key that unlocks the puzzle to his art.

Rafique Gangat, author of Bending the Rules, is based in Occupied Jerusalem.