Rabindranath Tagore’s Irish admirer

St Stephen’s Green is as Dublin as it gets. So how come there’s a statue here of Rabindranath Tagore when Ireland has a plethora of literary giants of its own?

Mallards splash with abandon in the watery weeds and reeds that ring the ornamental duck pond here in St Stephen’s Green, if not the heart of Dublin then certainly its soul, where the city’s comings and goings can be countenanced and contemplated.

For generations, Dublin’s dwellers and denizens have strolled the leafy tree-lined path around the Green, overlooked by mostly four-storey buildings that were once town homes to a merchant class in the second-most important city in the British Empire, with the houses built during the reigns of the four consecutive King’s George.

The entrance itself is marked by a dramatic granite and limestone arch monument erected in 1907 and dedicated to the men of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers regiment who served during the Second Boer War, with the names of 222 dead inscribed in the underside of the portal.

And it was across St Stephen’s Green during the failed 1916 Easter Rising against British rule in Ireland that rebels, holding the sturdy Royal College of Surgeons building, traded gunfire with British soldiers in the ornate Shelbourne Hotel. But both revolutionaries and regulars alike stopped shooting each day in a temporary ceasefire to allow the park keepers to feed a previous generation of those splashing ducks.

The park reeks of history.

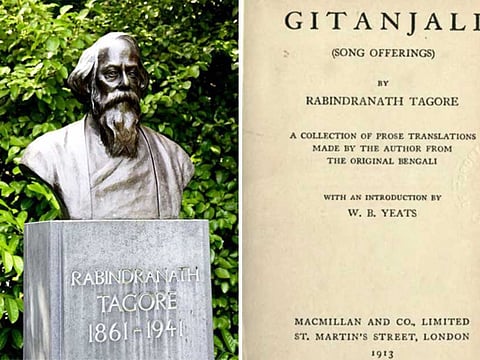

But cloistered in a quiet corner, among the sculptures to other Irish and British heroes of generations past, is one that stands apart in stony silence. It’s a bust of Rabindranath Tagore, the Bard of Bengal, the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the author of India’s national anthem and that of neighbouring Bangladesh too.

For the past seven years, the robed and bearded bard has gazed on from his home in the hedges from atop a stone plinth engraved with his name and years of his birth in 1861, and his death at the age of 80 in 1941. The bust was erected to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth. There is a second bust of India’s most famous wordsmith elsewhere too — in County Sligo in the northern corner of western Ireland.

The St Stephen’s Green statue was commissioned by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations and is a lasting reminder of Tagore’s literary influence on the two nations.

So how exactly did this man, who was born about 8,300 kilometres away, who began writing poetry in a corner of Kolkata at eight years of age, the youngest son of Debendranath Tagore — himself a Hindu philosopher and religious reformer — end up on a plinth and bust in this most Dublin of all places Dublin?

The answer is provided by Malcolm Sen, a native of Delhi who is assistant professor specialising in both Indian and Anglo-Irish literature. I caught up with him by telephone from the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at University of Massachusetts at Amherst in the United States.

The key connection is Irish poet and playwright William Butler Yeats, himself the recipient of the 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature, Sen explains in an accent that’s a strange mix of the subcontinent and Dublin where he studied, lived and lectured for 15 years before moving to the Boston area three years ago.

“Yeats was already a highly acclaimed and established poet with a considerable body of work to his name at the time of his first meeting with Tagore, in 1912,” Professor Sen explains. Sure enough, Yeats’s first volume of verse appeared in 1887. He and his wife, Lady Gregory, had previously founded the Irish Theatre, which eventually became the world-renowned Abbey Theatre. Yeats was its principal playwright until he was joined by John Millington Synge. Yeats’s father was a well-known lawyer and portrait painter, and W.B. was educated in both London and Dublin, easily moving between the first and second cities of the empire. His plays had made Yeats part of the end-of-century literary scene in London and, after 1910, Yeats’s dramatic writings turned towards poetry. He was also profoundly influenced by Japanese Noh plays and subsequently developed a longing for orientalism and its mystic elements.

“It was during Tagore’s third trip to England in 1912 that he met William Butler Yeats,” Sen explains. “At once, Yeats, already highly regarded himself, was besotted with Tagore’s writing, and was somewhat infatuated — I don’t think that’s too strong a word — infatuated with Tagore, his appearance, his beard, his manner, his mysticism. Certainly, Tagore appeared to be the living embodiment of what Yeats and his circle had imaged a mystic to be.”

Was it a meeting of like-minded poets?

“What we have at this meeting is really Yeats’s admiration, which is not spurred on so much by what he is reading, but by what he is expecting even before he has met Tagore,” Sen tells Weekend Review.

“Yeats is expecting what an Indian poet might be. Somebody who is highly spiritual, into the mystical arts,” says Sen, even if Yeats’s impressions of Tagore as a quintessential “mystical” Eastern poet were exaggerated. “Certainly, it seems as if Yeats was besotted with Tagore, and he literally raved about Tagore to anyone who would listen for the next three years or so. There certainly was a level of infatuation to the whole episode.”

Tagore had been partially educated at a public school in Brighton, nearly 80km south of London, and his family owned a house there.

At the time of their meeting, Tagore’s seminal work, Gitanjali (Song Offerings, 1912) had just been translated into English.

“Yeats was glowing over the translation and the works,” Sen says. “He was almost salivating, and that comes across in the words Yeats uses to describe Gitanjali. He wrote: ‘I have carried the manuscript of these translations about with me for days, reading it in railway trains, or on the top of omnibuses and in restaurants.’ He just couldn’t contain his approval and admiration for Tagore. And then, of course, a year after Gitanjali is translated into English, Tagore becomes the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literate. I guess the modern-day equivalent would be Bob Dylan, the singer, winning [the Nobel Prize for Literature] for his songs. It really was quite amazing.”

Later on, Sen explains, Yeats even arranged to have Tagore’s play, The Post Office — about a boy with a vivid imagination and an incurable illness — performed at The Abbey Theatre. That performance was on May 13, 1913, and the production went on a short tour of Ireland as well.

Superficially, the central theme of Tagore’s most popular play revolves around Amal, a sickly child eager to participate in the simple joys, the comings and goings, of life around him. Deeper, however, as Yeats noted, The Post Office is ultimately about deliverance, one that resounds in Amal’s death.

Indeed, to mark the centenary of Yeats’s birth and as a celebration of his influence, The Post Office was among early Abbey Theatre productions performed again.

“There is undoubtedly a strong element of infatuation, certainly in the way Yeats viewed Tagore,” Sen says, adding that at one point Yeats wrote that he had become so overwhelmed by his contemporary’s work that he’d had to put away the manuscript, “lest some stranger see how much it moved” him.

While Yeats was pressing Tagore’s case — at one point he noted about the translated Gitanjali “if someone were to say he could improve this piece of writing, that person did not understand literature” — Tagore himself had travelled to the United States to deliver a series of lectures at Harvard. By the time he returned to Europe, he had been transformed, Sen notes, from a relative unknown “to the latest epitome of all stereotypes oriental”.

“In large part to Yeats’s fawning, readers found Tagore’s poetry to provide more than enough sustenance — and his beard and flowing robe perpetuated that — to satiate their thirst for Eastern orientalism,” Sens observes.

There were also similarities between the west of Ireland, where Yeats spent his summers, and the nature of rural life of Bengal as elicited in Tagore’s works. More importantly, both Yeats and Tagore were influential and found expression in the growing sense of nationalism that would later on cleft both a divided Ireland and a divided India from the ranks of the British Empire. Those divisions for both new nations were also along religious fault lines.

“Certainly, Mahatma Gandhi was very influenced by Irish nationalists,” Sen notes, adding that the Constitution of India is based on that of the Irish Republic, written in 1937. It’s ironic too that the leaders of both Irish and Indian independence — Michael Collins and Gandhi — should die violent deaths in the nascent days of their nations’ freedom.

Indeed, Tagore himself was knighted by King George V in the 1915 birthday honours’ list as an imperial nod to acclamation bestowed with his Nobel Prize for Literature. The knighthood, however, was an honour that was to be returned to Buckingham Palace following the events of the Jalianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar on April 13, 1919. According to British estimates, 379 unarmed civilians were killed by Crown troops under the command of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, with some estimates putting the number of dead as high as 1,500. A disgusted Tagore returned his knighthood in protest at Dyer, a man contemporaneous press reports described as “the man who saved India”.

One historical aside in this dark chapter is that Brig Gen Dyer’s actions were adjudged to be “a correct action” by Sir Michael O’Dwyer, a native of County Tipperary who was then Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab. O’Dwyer was assassinated on March 13, 1940, by Indian nationalist Udham Singh in London.

Both Tagore and Yeats’s work were instrumental in shaping a consciousness and expression of nationalism at a time when the political realities on the ground in Ireland and the Raj meant coming in conflict with and walking a fine line against ruling authorities. It’s one thing to have finely crafted bodies of literature espousing traditions or perceived values of what it meant to be a true Bengali or Irish — another when it came to putting physical bodies on the line.

As it was, the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and the horrors of trench warfare quickly overtook any lingering fascination with orientalism. Perhaps too, the reality that troops from India were among the first to be committed by the thousands to the bloody stalemate unfolding in the newly dug trenches from the English Channel to the Swiss Alps helped shred any remaining notion of the aesthetic values of metaphysical eastern mysticism.

In Ireland, that nationalist violence found its expression in the events of East Week 1916, one chapter of which was played out in the park where Tagore’s statue now sits. It’s a shift that is noted too in Yeatss work, and his capture of that brutality is a certain factor in his claiming of the Nobel Peace Prize a decade after Tagore was awarded his.

What’s remarkable is that Yeats’s 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature was followed two years later by a similar accolade for George Bernard Shaw — an acknowledgement of a golden age for Irish literature that has contributed profoundly to the English language even today. Samuel Beckett in 1969 and most recently Seamus Heaney in 1995 have won Nobels for literature.

Tagore’s St Stephen’s Green sits just a short stroll away through the leafy park trees and benches — where those with too much time or too much of a good time shake off the excesses of life — from a statue to James Joyce. They are a contemporary park audience now to which Joyce could well relate. The Dubliner is perhaps Ireland’s greatest literacy figure to never win literature’s highest award, and his works are quintessentially Dublin in setting and nature — and St Stephen’s Green in a wholly appropriate location.

If there is a consolation for fans of Joyce — and for book lovers in general, it’s that come next spring, both Tagore and Joyce both share a park and paths that lead directly to the front door of MoLI — the proposed Museum of Literature Ireland.

Located at Newman House and an adjoining Georgian town home standing sentinel over the square park overlooking India’s most famous literary figure, MoLI is to open next spring, paying homage to Ireland’s literary tradition and to people like Tagore who became entwined in its writers and writings.

“It’s a project that began with conversations between University College Dublin (UCD) and the National Library of Ireland,” Simon O’Connor, the director of MoLI, says. “It’s a site that is actually the originally home of UCD” before it re-located to a new sprawling campus away from the confines of St Stephen’s Green.

Joyce himself attended university and graduated from the Newman House site. More importantly, perhaps, between the collections of UCD and those of the National Library, there was a need for a new facility to showcase the remarkable treasure trove of historical and important literary works that had been amassed — a new museum that would be able to do justice to the remarkable depth and breadth of Irish literature and its reach around the world.

Arguably Joyce’s greatest work, Ulysses is often considered to be one of the great novels of the last century. All of the events take place in a single day — June 16, 1904 — and the events in the book are recreated every year on that date — Bloomsday. St Stephen’s Green is indeed mentioned as a guide to Dublin more than a century ago as you follow in the footsteps and Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom and Molly Bloom.

MoLI will feature Joyce’s notebooks that detail his chaotic plot and thought process in creating Ulysses, and it also has the author’s personal priceless first edition of the novel

When MoLI opens next spring, it will a substantial visitor attraction for the literary history and culture of Dublin, O’Connor says.

So what makes Dublin such a rich literary city, with its authors able to engage with others, like Tagore, from half-way around the world more than a century ago?

O’Connor laughs.

“The answer to that question probably speaks to the entire artistic culture of the country,” he says. “we are an island. We have a complex colonial history. The weather’s not great. We talk a lot. We’re maudlin at times. We created our own competitive version of the colonial language — there are so many different factors. What is remarkable is that we have such influence far beyond our numbers. What’s remarkable too that so many of our writers wrote back to the country from abroad. You have Joyce who left. George Bernard Shaw. [Samuel] Beckett in France. It was always writing back, and the seeds of the writing were intertwined with the psychology of the country — with Joyce it was the psychology of the city.”

And that’s where MoLI comes in.

“What’s exciting about this project is that for such a small island, we have a complete imbalanced effect on English literature,” O’Connor says, adding that it will be a perfect and exciting location now to tell that history.

“One of the things too that’s important is how much our writers have influenced other writers,” he says.

Yes, how true. But when MoLI does finally open its doors, in the park opposite where those mallards play in the reeds and weeds, the statue to India’s greatest literary figure will still pay homage to Tagore — and the Nobel laureate’s more than passing influence on another who would later receive that same honour.

Mick O’Reilly is the Gulf News Foreign Correspondent based in Madrid.