An extraordinary testimony to art and suffering

An exhibition offers a fresh perspective on the Mexican artist’s compelling life story through her most intimate personal belongings

There is a self-portrait by Frida Kahlo that shows the artist’s bare torso split in two to expose a shattered spine, the result of a horrific bus accident at the age of 18. Her body is held together by straps. Tears stream down her cheeks and her poor flesh is everywhere pierced with sharp little nails. It is one of Kahlo’s most famous martyrdoms.

The painting is called The Broken Column, which throws the focus so completely on the spine — depicted as a ruined Ionic column —as to make the straps seem incidental, or perhaps as metaphorical as the architecture. But Kahlo (1907-54) really did live inside such a harness. The object appears in a show of her possessions at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and it is a horrific contraption of metal spars, cloth restraints and nail-like buckles. Its representation turns out to be the documentary truth.

That the art and the life were even more literally intertwined than anyone knew is the great revelation of Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up. Until 2004, the artist’s extravagant and instantly recognisable wardrobe was locked away in the Blue House in Mexico City where she lived and died, along with her jewellery, cosmetics, medicines and nearly 6,000 personal photographs. The house became a museum, which eventually put some of these objects on display. Now the V&A has somehow coaxed them out of Mexico for the first time, matching objects to drawings, paintings, letters and photographs to produce an intensely intimate portrait of the artist.

The photographs are extraordinary testimony in themselves. You see Kahlo working with her legs in callipers, confined to a wheelchair or even in bed. In one picture, immobilised by yet another botched operation on the spine, she lies horizontal beneath a suspended canvas, somehow continuing to paint.

Kahlo’s father was a German photographer, also brilliantly inventive. He made many self-portraits — caustic, comic, melancholy, nude — so that the idea of picturing one’s autobiography was already second nature to the young Frida. She helped him to pose, develop and retouch his photographs, and they were further united by illness: his epilepsy, her childhood polio.

Their bond is implicit in a terrific family photograph of German grandparents, Mexican matriarchs and all of Frida’s sisters, including Cristina, who would one day have an affair with Frida’s husband, Diego Rivera.

But where is Kahlo herself? She turns out to be the young man wearing her father’s suit and looking keenly out at him while leaning on the shoulder of a conspicuously affronted relative. It is the spryest of in-jokes.

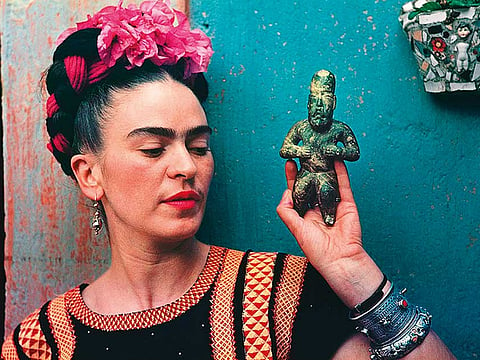

Kahlo’s androgyny — “in general, I have the face of the opposite sex” — coexists with the extreme femininity of her self-portraits. Cult followers will be able to see the actual relics: her favourite Revlon lipstick, the eye pencil she used to emphasise her monobrow, a jade necklace still stained with paint. In New York for medical treatment, she poses nude for a lover, unplaiting her elaborate headdress of hair into dark Rapunzel locks — always alluring, even in anguish.

She lived dying, said a friend, and not even the art can convey this to quite the same degree as certain objects at the V&A. A pair of black velvet shoes, for instance, tough yet elegant; but look twice: one has been tailored so that nothing might press down on her gangrenous toes. Or the red leather boots, wedge-heeled and embroidered with dragons, fit for Vivienne Westwood. One is still laced to Kahlo’s prosthetic leg.

More than 20 corsets were made to support her crumbling bones, some of steel, others of leather, including one resembling a heavy saddle. The V&A has plaster corsets, cast to her body while Kahlo was suspended upside down, one so tight she had to be rapidly cut free. Others she decorated with Mexican flora, or hammers and sickles.

“What do I need feet for if I have wings to fly?” runs the caption beneath a drawing of the amputated foot. Her courage in all this suffering staggers. One spotlit gallery contains 20 model Fridas clad in those long, full-skirted dresses that always seemed to be worn for political reasons — Tehuana national costume — but which now look, too, like magnificent camouflage for battered limbs. A sketch showing the artist vulnerably naked beneath her plumage confirms it.

Scholars have devoted themselves to the influence of religious symbols, Mexican communism and folk art on Kahlo’s painting, and this show will take in all three — the costumes she copied, the votive emblems she collected, the photographs of Lenin, Stalin, Marx and Trotsky (with whom she had an affair) pinned above her bed. But its significance is different and more original. It might be summed up in a drawing from 1937 that shows a many-handed Kahlo before the mirror, rearranging her face, altering her hair and simultaneously creating this self-portrait: in every respect, sui generis.

If the language of emotional martyrdom has sometimes seemed hard to take — Kahlo with sword to the heart, or as a running deer stuck with arrows — it now seems as if she made comparatively little of the medical horrors endured from the age of six to her premature death at 47. And more than that, she keeps up appearances — of both sorts — all through her life. A fragment of period film in this show reveals what looks like a dressing table loaded with cosmetics in the Blue House; in fact these turn out to be oil paints. But the connection is profound. Kahlo makes herself up — and then makes herself up once again, on the canvas.

Meanwhile, the American artist Cindy Sherman comes full circle at London’s Sprüth Magers, with a new series of photographs of ageing Hollywood stars from the 1920s and 30s, 40 years after her celebrated Untitled Film Stills of Hollywood starlets. In both, she plays all the parts. And so authentic is the image, once again, that it seems as if one recognises the actual actress — Marlene Dietrich in powerful red velvet, Bette Davis in a turban, the It girl Clara Bow now grown poignantly old.

Of course they are all fictions, and here, more than in any other show, Sherman’s special effects are all laid out in full view. The different shapes painted on her own concealed lips, the eyebrows erased and replaced with seductive crescents or surprised hyphens, the tinted powders and eyeliners that override the fixed colour of her own eyes. It is a masterclass in makeup, quite apart from anything else, so that in the latest shot, from 2018, Sherman appears as four completely different actresses with only a single shared characteristic — namely their ineradicable age.

One sees this in the thickening of the hands, neck and arteries, in the strength of the wrists and the force of the fingers — everything that cannot quite be concealed, either by these imaginary performers or the woman who portrays them. Some play with scarves to hide their wrinkles, others rely on a brave, haughty or mysterious expression. All could quite clearly carry off once more whatever roles they played on the silver screen until age edged them out of the system. But in each case there are a hundred more nuances, of doubt, pride, suffering, foolishness, survival, courage, learned from the life and irrepressible even in these supposed publicity shots for films that will never be made. The hands and eyes that cannot be masked, of course, quite conspicuously belong to Sherman, now in her mid-60s and with decades of superb work to her name. For the first time, perhaps, she reveals something of herself.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up is at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, until November 4.

Cindy Sherman is at Spruth Magers, London, until September 1.