The kind of thinking cities need

Progressive thought, reinforced by the undeniability of climate change, has overturned the ideas that prevailed in the 20th century

Day after day, under a bright sun, hours-long security lines snaked out of El Ejido Park, Quito, into the surrounding streets. Enterprising women in multicoloured skirts and brown hats sold water and folding umbrellas for shade. Inside, representatives at the German pavilion seduced passers-by with beer and apples to spread propaganda on the “circular economy”, while the incongruous sound of a mariachi band playing Frank Sinatra music wafted from Ecuador’s booth, nearly drowning out a speech by an architect from California describing her company’s projects to improve a slum in Kenya.

Habitat, the United Nations’ global cities summit meeting, is to urbanists roughly what Comic-Con is to Trekkies. Nearly 40,000 participants — dozens of mayors, a few heads of state, countless planners, environmentalists, transit wonks, energy officials, bicycle advocates, green energy executives, new-technology wizards, relief agency representatives, the list goes on — gathered here recently for the third Habitat ever, a chaotic, once-every-20-year event.

Notwithstanding the white noise of endless plenary sessions and the usual boilerplate speeches, I came away heartened. These weren’t just grey bureaucrats formulating dreary action plans. The crowd skewed young and idealistic. The United Nations issued an obligatory manifesto, the New Urban Agenda, intended to steer the growth of cities over the next two decades. Experts grumbled to me that, for maximum effect, it ought to have been hitched to more robust UN initiatives, such as those dealing with sustainable development and climate change, which many countries have signed on to.

But my takeaway from Habitat III had next to nothing to do with the official agenda and a great deal to do with what I sense is a worldwide sea change, a generational shift, rejecting the glum, defeatist view towards cities and urban life that prevailed when Habitat first convened 40 years ago in Vancouver, Canada.

Mother Teresa blessed that mostly forgotten event. Buckminster Fuller extolled recycling. Margaret Mead gave an inspirational speech. Tibetan Buddhists and Japanese Zen masters sat around a campfire with Hopi elders to lament the pillaging of natural resources and stress the urgency of environmental conservation. “It is of paramount importance,” stated the UN Declaration on Human Settlements in 1976, the manifesto that came out of Habitat I, “that national and international efforts give priority to improving the rural habitat.”

In other words, cities were a problem. This view prevailed through the 20th century. Cities were regarded as crime-ridden, unhealthy and polluted, ageing incubators of infant mortality and malnutrition, increasingly abandoned by the educated and the middle classes. Modernist architects and planners famously envisioned wiping the urban slate clean. They advocated Utopian, tower-in-the-park developments, high-rises in antiseptic plazas, with housing neatly cordoned off from offices, and highways bulldozed through old neighbourhoods to whisk people who could afford cars out of town. A brighter future beckoned in suburbia.

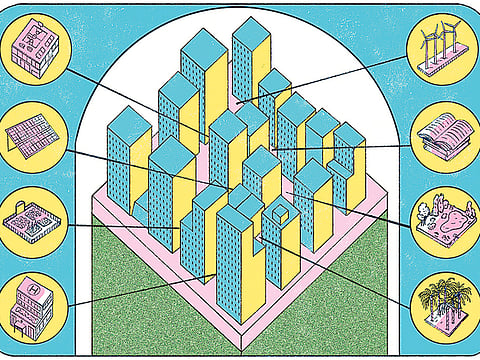

Today, progressive thinking, reinforced by the undeniability of climate change, has overturned those ideas. Cities are being recognised increasingly as opportunities for economic and social progress, density as a response to environmental threats; the automobile as a big problem; slums as not just a blight but a potential template for organic urbanism. Young generations around the world, entering the tech economy and bound by the internet, are embracing urban ideals, including the common ground of public spaces, mass transit, streets and sidewalks.

This news has clearly not penetrated the thinking of older leaders everywhere. From Caracas, Venezuela, to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, many cities in the developing world remain in thrall to obsolete, environmentally irresponsible, socially debilitating visions of high-rises and highways, sprawl and segregation, with poor people pushed to the outskirts and more well-to-do residents in gated communities that are yet another unfortunate global export from postwar America.

Federal authorities often thwart initiatives by mayors, who know the benefits of cities best. I found Miguel Angel Mancera, the mayor of Mexico City, at the conference. He told me that Mexico’s federal government in September slashed funding to Mexico City by billions of pesos, interrupting critical repairs to the strained metro system and to the precarious system of water pipes upon which tens of millions of residents rely. Instead, the national government is funding sprawl and building double-decker highways, paving the path to ruin.

This is where the youthful spirit I found at Habitat comes in. The ethos here stressed grassroots, environmentally conscious, entrepreneurial urban development. There was lots of righteous talk about redistributing real estate profits and treating housing as a basic human right, but also about how investments in things such as public transit and infrastructure pay big economic dividends — how good cities are not just equitable and green but good for business.

That young California architect trying to talk over the mariachi band was Chelina Odbert, who directs Kounkuey Design Initiative, an architecture firm that has spent years collaborating with residents in Kibera, a large slum in Nairobi, Kenya. At Habitat, she showed slides of some of the new public spaces, offices, urban farms, sanitation facilities and community centres that have resulted, which in turn have generated jobs.

She belongs to this new generation that is changing the conversation about cities. Despite the noise, she made herself heard.

–New York Times News Service