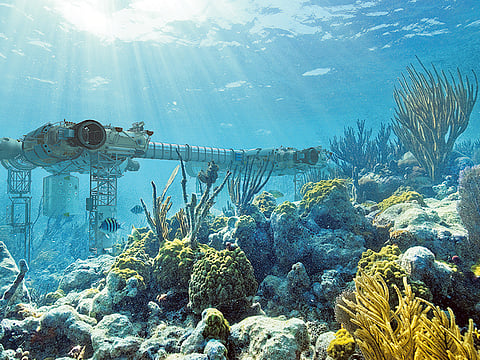

Mining the deep blue sea

With rare earth metals potentially running low, deep sea mining is getting a second look

Boston: The risk of running out of rare earth metals that are essential to modern technology has led to a surge in interest in mining the deep seas.

But fears have also mounted about the environmental impact of disturbing vast areas of the pristine ocean floor, experts said at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual conference in Boston.

Demographic growth and the acceleration of technological innovations in the past 40 years have doubled the quantity of minerals extracted worldwide, leading to shortages of certain key metals, according to a recent UN report.

“Mining is essential for modern life,” said Thomas Graedel, professor emeritus of industrial ecology and chemical engineering at Yale University.

“If global development proceeds at its current pace, traditional land-based supply of resources may be challenged to meet demand.”

When it comes to copper, an essential element for electrical equipment and numerous industries, a shortage could begin around 2050, he said.

This uncertainty highlights the importance of considering deep-sea mining, even though the process involves environmental risks.

Cobalt, iron, manganese, platinum, nickel, gold and other rare earth minerals are generally found at depths ranging from a few hundred to several thousand metres (yards).

But just how much valuable material lies beneath the ocean floor remains highly uncertain, said Mark Hannington, a geologist at GEOMAR-Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Germany.

Observations so far indicate that sea floor deposits targeted for mining could include from 600 million to a billion tonnes of minerals, including 30 million tonnes of copper and zinc, resources which could help respond to growing global demand for electronics.

He also said that nodules — or rocky formations containing valuable metals on the ocean floor — “are enormously abundant.”

But details on this potential remain poorly understood, because for the past three decades, exploration has been concentrated on certain areas near hydrothermal vents.

“We have not found the large deposits yet,” said Hannington.

“We have got to figure out how to find them if we want to truly understand the resources,” he added.

“We’ve got to speed up the process dramatically because it has taken 30 years to get where we are now and 30 years from now it will be too late.”

He added that all the zones granted exploration permits so far represent only 0.5 per cent of the total area that could be mined in the ocean.

Until now, 27 countries including India and China have signed contracts to explore for these resources with the International Seabed Authority, the body charged with controlling exploration and exploitation of the areas beyond national borders.

But given the sizeable risks to fragile ecosystems, a new international approach to managing mineral deposits should be put in place, according to a recent report published in the journal Science.

“Waters deeper than 200 metres make up 65 per cent of the world’s oceans, and are vulnerable to human activities,” it said.

“Cumulative impacts could eventually cause regime shifts and alter deep-ocean life-support services such as the biological pump or nutrient recycling.”

Stace Beaulieu, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, warned of the risks.

“The hydrothermal vent ecosystem may be subject to catastrophic impact from mining with a loss of habitat and associated organisms,” said Beaulieu.

“These vents are significant ecologically and biologically and there is also an unknown biodiversity nearby,” she added.

“We have to look at the economic value of these ecosystems, the potential trade off.”