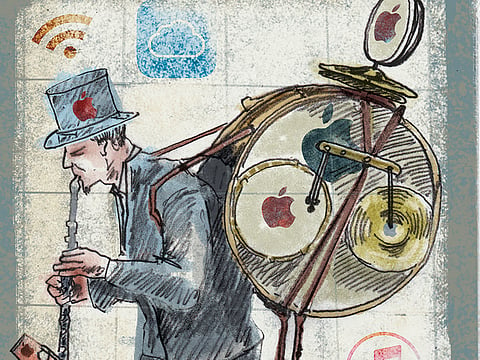

Apple thinks of life after the iPhone

Content services battle with the likes of Spotify and Netflix will be pivotal to its future success

London: There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share,” barked former Microsoft chief executive Steve Ballmer during an interview in 2007. “No chance.”

Ballmer, colourful and charismatic though he is, proved to be a poor prophet.

Seven months after his damning indictment, Apple’s first smartphone went on sale and redefined the mobile industry, putting computing in millions of people’s pockets for the first time.

Despite, or maybe because of Apple’s die-hard commitment to absolute secrecy ahead of its launches, the usual flurry of leaked images, rumours and pure conjecture that’s flooded the internet for the past few months has reached fever pitch.

It isn’t hyperbole to say that Apple is the only company with the clout to command the world’s attention in this manner, as the inevitable crowds of excitable fans itching to set up camp outside its retail stores, from Australia and Germany to the UK and China for the chance to buy the new iPhones, will attest.

It also has the blessing of pop darling Taylor Swift, as Apple Music is the only streaming service with the rights to her back catalogue. The event comes at an interesting point in Apple’s history.

This year the company announced the biggest quarterly profit made by a public company — some $18 billion (Dh66.11 billion) — and launched its first new product since the death of Jobs, the Apple Watch. It’s proved it can innovate in the absence of Jobs’ maverick vision, and maintain its position as the world’s most valuable company.

But what happens when the yearly iPhone hype is no longer enough? Analysts are sceptical whether this year’s upgrades will drive customers to Apple stores in their droves the way last year’s did, especially when accompanied by their unapologetically high price tags. IDC, a researcher, has forecast Apple to ship 232.7m iPhones in its fiscal 2016 compared to 233.8m in 2015 — which would be, if true, the first year-on-year decline in iPhone shipments.

Needless to say, analysts have often severely underestimated Apple. The iPhone is indisputably the core of Apple’s business. Following in the footsteps of the iPod six years previously, its launch in 2007 marked the company’s second-wave offensive as a high-end consumer electronics manufacturer and away from its computer-heavy past. Apple's Steve Jobs chose the launch of the “revolutionary and magical” iPhone to announce the symbolic decision to drop “Computer” from the company name and rebrand as Apple Inc. The wheels were set in motion.

Jobs’ unshakeable belief that people would buy the iPhone helped to propel it from strength to strength. Sales of the smartphone range accounted for 69 per cent of Apple’s $74.6 billion global revenue during its record-breaking first quarter of 2015, with the larger screens of the iPhone 6 and 6 Plus helping to drive iPhone sales alone to 74.6 million units — the equivalent of 34,000 phones flying off the shelves every hour.

Such figures inevitably lead to tough year-on-year comparisons, especially given worrying forecasts that the smartphone market is reaching saturation point. Following years of spectacular growth fuelled by emerging markets in China and India, worldwide smartphone sales recorded the slowest growth rate during the second quarter of 2015 for two years, according to Gartner.

Sales within China, the world’s biggest smartphone market, fell 4 per cent year-on-year, the first time they have fallen there. China’s current economic uncertainty, coupled with the fact that the country is shifting from a first-time consumer of technology to an upgrade economy, is an obstacle to continued growth.

Apple has weathered this: solid demand among China’s middle classes for iPhones led to a 68 per cent rise in sales during the period in the face of the downturn. Such is Apple’s cachet within China, when regulatory approvals delayed the iPhone 6’s release imported units commanded more than twice their face value on the black market.

“There is a question over how much the economic situation in China is affecting the ability of the consumer to purchase those devices,” says Geoff Blaber, head of mobile device software research at CCS Insight.

“Despite a clear slowdown across the broader phone market, Apple is dominating the higher tier across many of these markets, without diversifying like many of its rivals.”

Apple’s strategy, he maintains, will be to continue gradually widening its product portfolio while slightly lowering the pricing of older devices to introduce new entry points. Higher margins on new products thanks to aggressive price increases in recent years will continue to generate huge amounts of revenue, providing the demand is still there.

The delicate alchemy of desire and demand is something Apple has proudly perfected.

“A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” Jobs once said, which in retrospect acts as a neat summary for Apple’s approach to the phone, tablet, laptop, desktop, music player and smartwatch markets; instead of inventing these categories, it redefined them. Apple knows it can’t rely on the annual iPhone hype-release cycle forever.

The next wave of growth is likely to come from calculated investment in content and services, reaching beyond the rush of unboxing the latest iProduct and quietly wrestling power away from the digital companies we’re increasingly reliant on for entertainment — namely Spotify and Netflix.

Apple has preferred to wait and monitor the growth of the streaming subscription industry rather than rushing out its own offering. Yet its own content services made more than $5 billion during its most recent quarter, including iTunes, the App Store and Apple TV.

Apple Music, its on-demand music service launched this year after the $3 billion acquisition of Beats Music, the audio company founded by rap star Dr Dre, was a late entry to the music streaming arena. But early figures from the company released in a rare act of transparency put the number of users opting into the three-month free trial at an impressive 11 million.

While the real issue lies in convincing those users to pay £9.99 per month once the trial runs out, it demonstrates how quickly Apple can amass the number of users Spotify took years to accumulate.

Though unlikely to be revealed next week, Apple is rumoured to be working on its own subscription streaming service to compete with Netflix.

Reports suggest that Apple was involved in a bidding war for former BBC Top Gear trio Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond and James May, which resulted in the presenters signing with Amazon. Should Apple invest in development and production divisions for its own TV programmes and films, it could prove extremely disruptive to the blossoming video streaming industry, which is predicted to generate revenues of £1.17 billion in the UK alone by 2019.

For years, the trend in television watching has been the shift away from the living room television set, as a younger generation embrace internet video on their tablets, smartphones and laptops. The major upgrade to Apple TV expected this week marks an attempt to change that. But where Apple’s advantage lies is that it may not only be creating the programmes, but will also sell the so-called “second” and “third” screens — the smartphone and tablet that have become so intrinsic to the 21st century viewing experience.

“Services and software will be key on the hardware market truly slows, and with a future streaming service through Apple TV, they would be going down the road which makes the most sense,” says John Butler, senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

“They’ve got the market and the brand name to dominate it, and they would be playing to their strengths through iTunes distribution and the iPhone second screen leveraged through their content and services.”

Peter Csathy, chief executive of Manatt Media, suggests that Apple’s deep pockets afford it much more freedom that its competitors, namely in subsidising the cost of its content licensing and original programming in order to keep subscription costs down.

“Through its closed ecosystem, Apple influences us in terms of what we want to consume,” he says. “It has the luxury of being able to start a streaming business with a captive audience which is profitable, with the added advantage of acting as a marketing exercise for its Apple TV hardware.” Yet the step of buying Netflix outright, while possible, is unlikely. “When Apple bought Beats, it was to buy the key relationships with music industry figures like Jimmy Iovine,” he adds.

“It could have bought Spotify, but it made a more economical purchase with Beats. Apple could achieve the same by purchasing a Netflix competitor to gain what it needs from them.”

Apple is hoping to develop beyond the product roll-outs and dig deeper into mobile payments, the connected smart home, and eventually its rumoured electric self-driving car. In short, it is more focused than ever on becoming the platform of choice for our everyday lives. The programmes, films and music we consume through its iPhones, iPads and MacBooks could make even more money for Apple than the devices themselves. But for those of us on the outside of Apple’s fortress, the only thing we can safely predict is the glitzy events to herald their arrivals.

— The Sunday Telegraph