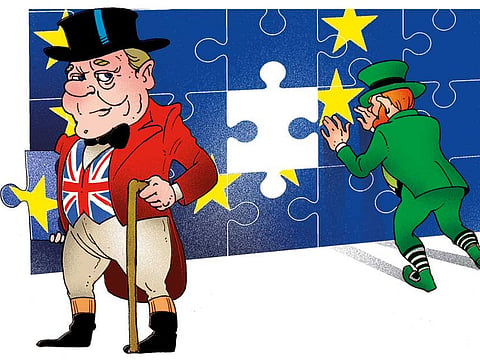

Why the Good Friday agreement is still relevant

In the wake of the Brexit vote, the treaty’s recognition that identity is complex and changeable seems all the more vital

Twenty years ago, when the Good Friday agreement was signed, there were many emotions in the air: Hope, relief, a kind of giddy fatigue. There was, however, no euphoria. This was partly because everyone knew the conflict that was being brought to an end had been slow and sordid. It had been allowed to drag on long after victory for any side had become an obvious impossibility. There was too much sorrow, too many lives lost or blighted for no purpose, for unabashed exultation to be either warranted or decent.

But there was also a better, nobler reason for the absence of real jubilation. The agreement wasn’t about winning. Its signing was not one of those epic, historic moments when a Bastille falls or a wall is torn down. It was, in fact, the exact opposite: A mutual acceptance that no such millennial moments were in prospect for anyone. There was not going to be a grand ceremony when all the union jacks were hauled down and the British army marched off to the ports, never to return. Neither was there going to be a surrender of the IRA, an abject renunciation of the demands of Irish nationalism.

On the contrary, what the agreement was really about was devising a way for everyone to get over the loss of such dreams of once-and-for-all victories. It set an example that might have done a great service to the rest of Britain. But as Barry Gardiner’s characterisation of the agreement as a shibboleth, and the constant drumbeat of dismissiveness from pro-Brexit extremists have made clear, that lesson has yet to be learnt.

The genius of the agreement was that it took an unanswerable question and changed it. The unanswerable question was: What are you prepared to die for? A United Kingdom or a United Ireland? They were mutually exclusive concepts. The new question was not what are you prepared to die for, but what are you willing to live with.

The Good Friday gamble was that people could live with complexity, contingency, ambiguity. Twenty years on, in a world that is spinning backwards into the worst kind of identity politics, the agreement seems to matter even more than it did in 1998, precisely because it makes tolerance of uncertainty the great civic virtue.

Part of that uncertainty lay with the agreement’s own moral ambiguity. There is no hiding the fact that it made concessions to killers, including the release from prison of some mass murderers. Nor is there any point in denying that its provisions for the internal governance of Northern Ireland actually exaggerated and institutionalised sectarian divisions. The language of “parity of esteem” between “two traditions” — Protestant/unionist versus Catholic/nationalist — essentially ignored the third tradition of those who did not wish to be defined by these tribal categories.

And the cost of this has been huge. The middle ground from which the agreement itself came has been narrowed. The moral and intellectual architect of the agreement, John Hume, had to watch his own Social Democratic and Labour Party be eaten up by Sinn Fein. On the other side, David Trimble’s Ulster Unionist party, which signed the agreement, has been displaced by the Democratic Unionist party, which did not. “Parity of esteem” quickly came to be translated into a logic of tribal competition that has undermined the very institutions it was meant to sustain.

These problems need to be addressed, and if it were not for the crazy distractions of Brexit, the 20th anniversary would be a very good occasion for a fundamental review of the agreement’s internal workings. They should not, however, detract from the boldness, radicalism and imaginative brilliance of the agreement as a whole. It did something that sovereign governments had not done before, which is to create a political space that is claimed by nobody — a space, moreover, that exists not in a physical territory but inside people’s heads.

At the core of the agreement is its statement that people born in Northern Ireland have an absolute right to be “Irish or British or both as they may so choose”. We have here, written down in a binding international treaty, a recognition that national identity is not a territorial or genetic imperative, and is not necessarily a single thing. It is chosen, and therefore open to a change of mind. And it can be multiple: Those six letters — “or both” — are the glory of the agreement, its promise and its challenge.

The agreement tries to replace either/or with both/and. It comes from the bitter knowledge that either/or — Catholic or Protestant, unionist or nationalist, Irish or British, them or us, victory or defeat — is a deadly option. It holds up a notion of purity that is neither attainable in practice nor desirable in principle. Both/and pushes away the illusory satisfactions of purity and seeks out the common decency of everyday life, in which we all live with complex ideas of belonging.

What we did not imagine 20 years ago was that the pursuit of a pure identity would return as a governing project — not in Northern Ireland, but in England. We could not have foreseen that the euphoria of victory would animate politics on these islands again. It seemed, in those days of sober hope, that we had all gone beyond thinking that people could belong to only one thing.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Fintan O’Toole is an author and columnist for the Irish Times.