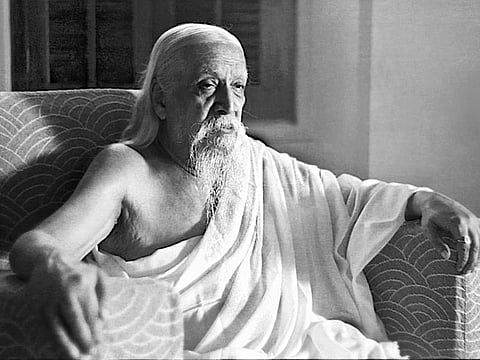

Why Sri Aurobindo continues to be relevant on his 150th anniversary

The great Indian philosopher’s message and work offer unique vision for global well being

In an earlier column, I commented on the fortunate coincidence that India’s 75th anniversary as a free country also concurs with Sri Aurobindo’s 150th birthday. Aurobindo (1872-1950) was a poet, revolutionary, philosopher, mystic, and yogi par excellence.

With his spiritual associate Mira Alfassa (1878-1973), he went on to establish the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry. Along with its off shoots, Sri Aurobindo Society and Auroville, the Ashram and the disciples of Aurobindo have spread his life affirming message worldwide.

What was unique about Aurobindo? Well, almost everything. The essence of Aurobindo’s philosophy is that a conscious, spiritual evolution on part of the human race is the only way to solve some the problems that face humankind.

These intractable challenges included violence and war, social and political inequality and instability, and the man-made ecological threat to our habitat, which puts the very survival of the species at risk.

A child prodigy

Aurobindo’s father, Krishnadhan Ghose, was a surgeon and an Anglophile. The family moved to England when Aurobindo was seven. Aurobindo matriculated from St Paul’s School, London, then got a first class in the Classical Tripos at Cambridge, a rare feat for a non-European. His father wanted him to be an Indian Civil Service officer.

Aurobindo passed the written exams, but could not qualify because he failed to appear in the mandatory riding test. Instead, a meeting with Sayajirao Gaekwar, the ruler of Baroda in 1892 secured him service in the Baroda State. Aurobindo returned to India the following year, when he was twenty.

Already a prodigy, Aurobindo rose to the forefront of the national movement, causing a split in the Congress Party in the Surat session of 1907. He belonged, along with Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal, to the so-called “garam dal” or extremist faction, who believed that freedom from colonial rule could not be secured just be “petition, prayer, and protest.”

In 1907 Aurobindo moved to Calcutta to become the Principal of the newly established National College (now Jadavpur University). He was also the brains behind a revolutionary group. Arrested in the Alipur Bomb case, he spent a year in jail from 1909-1910.

A few months after his release, he suddenly decided to leave British India for French Pondicherry. He withdrew from politics to practice yoga.

A prolific thinker

From 1910 until his death in 1950, Aurobindo wrote a series of extraordinary books including The Human Cycle, The Idea of Human Unity, Essays on the Gita, The Synthesis of Yoga, The Secret of the Veda, and The Life Divine. He also wrote what is one of the longest poems in the English language, Savitri, over 24,000 lines.

One of Aurobindo’s works was published posthumously as The Foundations of Indian Culture. Originally a series of articles in his own journal, Arya, it was meant to be a vigorous critique of imperial attempts to belittle Indian civilisation.

Aurobindo begins by stating unequivocally how a culture or civilisation may be evaluated:

"A true happiness in this world is the right terrestrial aim of man, and true happiness lies in the finding and maintenance of a natural harmony of spirit, mind and body. A culture is to be valued to the extent to which it has discovered the right key of this harmony and organised its expressive motives and movements."

When Aurobindo wrote these lines, there were no internationally recognised yardsticks, such as Human Development Index, for evaluating the quality of human life.

But Aurobindo underscores how materially affluent societies can still be unhappy and discontented. Why? Because, according to Aurobindo, any country which caters only to the body or even to the body and the intellect, but leaves out the spirit cannot achieve true happiness. Without provisions to nourish the spirit, human beings cannot attain perfection.

Harmony between physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual

Aurobindo holds that the material can serve as a platform or aid, but, ultimately, human flourishing is about self-actualisation not technological and monetary advancement. Because India has devoted itself to seeking the self and finding liberation, Aurobindo considers it special.

This does not mean the satisfaction of bodily or mental needs is not important. But a harmony between the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual is necessary for human beings to attain their full potential.

Aurobindo acknowledges that there are nations and cultures which are led by a different, even opposite conception of human life:

"Since some centuries Europe has become material, predatory, aggressive, and has lost the harmony of the inner and outer man which is the true meaning of civilisation and the efficient condition of a true progress."

Those of us who are mesmerised by the West would do well to reflect on Sri Aurobindo’s statement. Surely, the essence of civilisation does not lie in killing others, destroying their culture, enslaving them, grabbing their wealth, and ruling over the world.

Finally, Aurobindo believes that “Each nation is a Shakti or power of the evolving spirit in humanity and lives by the principle which it embodies.” If so, a clash and conflict between nations is inevitable, but certainly not permanent. In fact, Aurobindo defines the three stages of the interaction between nations: “conflict and competition, concert, and sacrifice.”

Looking at his own times, Aurobindo admits that “An appearance of conflict must be admitted for a time, for as long as the attack of an opposite culture continues.” But later, this very conflict, will “culminate in the beginning of a concert on a higher plane.”

In the final stage, nations may even sacrifice themselves for the good of the whole of humanity, foregoing their selfishness and self-interests.

We are still far away from Aurobindo’s ideal of human unity. But more than ever we need to work towards it to ensure global peace and prosperity.