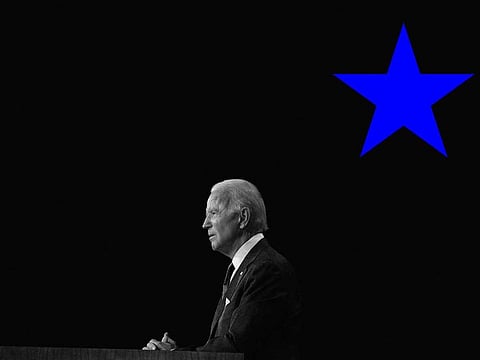

This is how Biden can win in November

Democratic leader needs to be the real “law and order” candidate in this crucial election

There’s one thing about the people on the Trump team that I almost admire: When they do blurt out the truth, they really tell you the truth — in a way that’s so raw you’re left asking, “Did they really say that out loud?”

That was certainly my thought when Kellyanne Conway declared last week, “The more chaos and anarchy and vandalism and violence reigns, the better it is for the very clear choice on who’s best on public safety and law and order.”

The better it is? How could anyone be “better” in America if we have more chaos, anarchy, vandalism and violence? It couldn’t be better — except for one man: Donald Trump.

Alas, it’s true: Every scene of rioting and looting is probably worth 10,000 votes for Trump’s reelection campaign. Just ask Kellyanne.

So, Joe Biden has a real challenge on his hands. To mobilise the majority he needs to credibly assure enough voters that he takes both the violence seriously and its social, policing and economic roots seriously. His “looting is not protesting” speech in Pittsburgh on Monday was a good start.

If you want to understand just what a challenge Biden faces in this election, though, study the struggle in my hometown, Minneapolis, over policing. It’s a face off between some unlikely foes and, so, it reveals deep truths.

On one side are the super liberals on the Minneapolis City Council. They voted in June, after George Floyd’s death at the hands of local police, to begin a process to remove the requirement of the City Charter to maintain a police department.

It would be replaced with “a department of community safety and violence prevention,” with a director who would have “non-law enforcement experience in community safety services, including but not limited to public health and/or restorative justice approaches.” A division of “licensed peace officers” would answer to that director.

Among those opposing this change is a budding coalition of Black and white community leaders from North Minneapolis, the historical home of the Minneapolis Black community. (I was born in the Northside in 1953 when it was also the home of the Jewish community.)

They are unnerved by the notion of dismantling the police force for a vague alternative at a time when their neighbourhood has experienced a surge in gang shootings, lootings and drug dealing — all exacerbated by the pandemic, spiralling unemployment and demoralised police officers, who, after the Floyd killing, don’t always have the numbers or the will to show up.

Also Read: COVID-19: America’s war with masks

On Aug. 18, this coalition — four Black and four white families from North Minneapolis — filed suit against the City Council and the mayor, Jacob Frey, to compel them to maintain the legal minimum of police officers on the Minneapolis force.

The families contend that the council’s actions have driven out too many police officers and curtailed the hiring of replacements, endangering their neighbourhood.

An uncertain replacement

Don’t get them wrong, the plaintiffs argue, they want thoughtful and deep police reform. But they want a better police force enough police officers to protect their kids and their streets — not the present unreformed police a disbanded police department and an uncertain replacement.

The Star Tribune of Minneapolis reported Aug. 1 that since the killing of George Floyd in late May, the city’s police force is down at least 100 officers, more than 10% of the force, “straining department resources amid a wave of violence.”

The department, the newspaper added, is budgeted for 888 officers this year but could lose as much as a third of its workforce by year’s end — through resignations, firings and medical leave for post-traumatic stress from the violence that followed Floyd’s death.

In an Aug. 24 op-ed in The Star Tribune, Sondra and Don Samuels, two of the Black plaintiffs, explained why they are suing. I know them both, and they are deeply involved in improving their Northside neighbourhood.

Sondra is the chief executive of the Northside Achievement Zone, and Don, her husband, is a former City Council member, former Minneapolis school board member and chief executive of Microgrants, a local non-profit.

“We want radical police reform, where all citizens are treated as fully human by all cops, and not just by the ‘good ones’ we all know well,” they wrote. “We support the reform moves of the mayor and chief, which include community alternatives to policing that work hand-in-hand with our police force.”

The state Legislature, they also argued, “must change arbitration rules that too often demand bad cops be rehired after being fired for abusive policing.”

But, they added: “We will not sacrifice the safety of our community in the pursuit of the City Council’s lofty goals with no plan to back them up. In the months since George Floyd’s murder, we have seen an explosion in crime and homicides. Five of us live just a few houses apart.

Four of us have children in our homes. Here’s what we’ve experienced on our block alone over the last two months:

“A mother’s car was shot up with eight bullets, with her infant on board. Another car was shot four times. A bullet went through the front door and a wall of our neighbour’s home.

A woman was kicked and stomped within inches of her life in the middle of the street. The drug trade has been revived in two homes, to unprecedented levels, with conflicts resulting in fights and shoot-outs.”

The chaos and violence

Besides big stores, like Saks and Nordstrom, which were vandalised last week in downtown Minneapolis — after rumours spread that police had shot a Black man, who, it turned out, had actually killed himself — a slew of Northside businesses owned by people of colour were looted or vandalised during the George Floyd protests, and many owners are now afraid to rebuild.

Think about the Northside Achievement Zone that Sondra runs. It’s working with parents, students and local partners in predominantly Black North Minneapolis to end multigenerational poverty through education and fostering family stability.

It’s been a real engine for building healthy community and enabling Black Americans to realise their full potential. But it can’t work in chaos.

“We have to be able to say both that Black lives matter and that protests that turn violent cannot be allowed to tear up our city,” Sondra said to me.

But we have to say a third thing, she continued — it’s what Martin Luther King Jr. said in the late 1960s, and it’s as relevant today as it was then.

King decried riots as “self-defeating,” but he also pointed out that “a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years.

It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. It has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquillity and the status quo than about justice, equality and humanity. And so in a real sense our nation’s summers of riots are caused by our nation’s winters of delay.”

Economic progress and social justice, King argued, “are the absolute guarantors of riot prevention.”

Which is why Biden, if he frames it right, can be the real “law and order” candidate in this election. Because he’s not for disbanding the police but for improving them — which is how you build respect for the law from — and because Biden knows that sustainable order can only come from a president who wants to build healthy and just communities, not from a president who thinks it’s “better” for him politically if they’re torn apart.

Thomas L. Friedman is a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist and author.

The New York Times