India-Japan nuclear deal and political bugbear

The political discourse in India should not distort the orientation adopted by previous governments and seek any kind of Faustian bargain for short-term political dividends

Two significant developments have taken place over the last week in the nuclear domain that will have a long-term bearing on India’s overall nuclear profile over the next decade. It will be instructive to see how these issues will be mediated in the current Indian political cauldron.

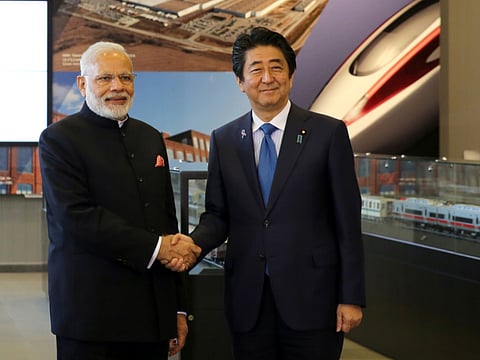

The developments relate to Japan and China — but differently. The major punctuation relates to Prime Minister Narendra Modi concluding a long-awaited civil nuclear agreement with Japan (on November 11), though there are some tangled areas of interpretation on certain key clauses. The second pertains to India’s bid to become a member of the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG) and China’s steadfast opposition to this aspiration. Beijing reiterated that, as regards the NSG meeting held in Vienna (when Modi was in Tokyo), being an NPT (Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty) signatory is essential before considering membership.

This, in reality is a veto — since India cannot sign the NPT as a nuclear-weapon state — and renouncing nuclear weapon capability like many such states (including Japan) is not an option.

The conclusion of the Nuclear Cooperation Agreement (NCA) in Tokyo by Modi with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is particularly significant — both for its symbolism and its substantive implications. Japan has a very deep sensitivity with regard to the nuclear issue and was firmly opposed to India’s nuclear tests of May 1998. However, the rapprochement between India and the United States in 2008, epitomised by the conclusion of New Delhi’s civilian nuclear agreement with Washington, and the exceptional status accorded to India by the NSG in September 2008, encouraged Tokyo to review its opposition to India’s nuclear aspirations.

This progressive shift was enabled by the personal determination of Abe — and in many ways his resolve could be analogous to that of the then US president George W. Bush, who invested his personal political capital in squaring the nuclear nettle with India in the tumultuous 2005-2008 period.

When India was negotiating with the US in that tense phase — one central determinant was India’s ‘right’ to conduct another nuclear test — should its supreme national interest warrant such a step. It was evident to domain experts that there was no way that even a determined Bush could have pushed through any template that did not satisfy his critics — in the US Congress and among the nuclear mandarins (opposed to any modus vivendi with India).

Domestic political compulsions pushed the deal with the US to the very brink and finally some deft legislation (the Hyde Act in the US Congress) and adroit drafting consensus by the two principal negotiators allowed the civil nuclear agreement to be realised — but it literally came down to the wire. At the very last stage, more assurances were sought from India that it would continue its ‘restraint’ and India’s then External Affairs minister Pranab Mukherjee made a formal statement to this effect on September 5, 2008. Two days later, on September 7, India received the NSG waiver it had sought and a long period of nuclear isolation and intimidation ended.

Venal political opposition to then prime minister, Manmohan Singh, within his own Congress party — and to the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) initiative by the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Left parties — almost torpedoed what can be described as the most significant national interest enabler in the nuclear domain. It ended India’s ostracism. The Bush-Singh resolve ensured the according of exceptional status to India by the NSG despite the fact that India was and is a non-signatory to the NPT, and that it had acquired nuclear weapons.

At the time, many experts applauded India for its tenacity and negotiating acumen.

Regrettably, a zero-sum template has permeated Indian political conduct even on matters pertaining to national security and this is most evident in the nuclear domain. The Congress could not accept that a BJP-led government with Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the helm had taken the decision to cross the nuclear rubicon. Acquiring nuclear weapons was castigated by the Congress — when in the opposition — despite the fact that former prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao had, in 1995, considered carrying out a nuclear test.

The tables were turned when the Congress formed the UPA government in 2004 and the BJP-led opposition keel-hauled Manmohan Singh for entering into a civilian nuclear agreement with the US in July 2005. Any number of hurdles — imagined and exaggerated — were introduced into the domestic political cauldron and the negotiators and their political principals on both sides must be commended for staying the course till late 2008.

But the deeper political understanding was that India would remain committed to its self-imposed moratorium so far as nuclear testing was concerned — first outlined by Vajpayee in 1998. This unwavering fidelity to nuclear restraint accorded India an intangible virtue index and this came to the fore in the Kargil war of 1999 with Pakistan. India was acknowledged as a responsible and virtuous nuclear power.

Today, the agreement with Japan is caught in an opaque zone of interpretative nuance — about nuclear testing. Stock phrases like sovereign right being trampled are being heard — and suggestions made that India is conceding more to Japan in 2016 than it had to the US in 2008. This kind of sophistry is undesirable and imprudent.

India’s exceptional status in the nuclear domain is predicated on its restraint and adherence to the self-imposed moratorium that goes back to 1998. Yes, India can claim the ‘right’ to test — should an exigency of grave import necessitate such a step. But this step will automatically impose certain costs on India and objective cost-benefit analysis will be called for.

In the interim, the political discourse in India should not distort the orientation adopted by previous governments and seek any kind of Faustian bargain for short-term political dividends. India should not renege on solemn commitments made by clever sleight of word to assuage domestic sentiment. The agreement with Japan should be upheld and interpreted in a manner that will burnish India’s virtue cum rectitude index.

— IANS

C. Uday Bhaskar is director, Society of Policy Studies, New Delhi.