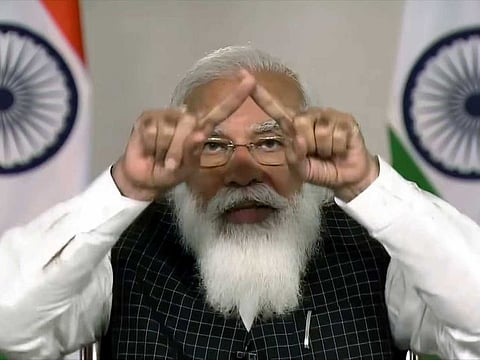

COVID-19 second wave: What are Narendra Modi’s real ratings?

A SWOT analysis of India’s Prime Minister still points to an advantage for the incumbent

India is in mourning. Its faces an existential crisis. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has said that the second surge is a “once in a century crisis.”

As on May 18, 25 million Indians have been infected by COVID-19 while more than 279,000 Indians have died officially because of the pandemic. Many thousands may have succumbed but those deaths are not notified as anarchy prevails at all levels.

Few years back, Jairam Ramesh, top Congress leader in India's upper house of parliament, Rajya Sabha, told me that whenever Narendra Modi’s downfall will come, it will be sudden and steep.

Can this unimaginable and unprecedented catastrophe, caused by the coronavirus, impact Modi in a way Jairam Ramesh was suggesting? The answer will come only in the 2024 general elections but meanwhile, here, is an attempt to analyse where Prime Minister Modi stands in the midst of India's national crisis.

Strength

As of today Modi’s strengths are diminished. How can the country’s top leader remain strong when millions of Indian families are in mourning? However, in the darkest of times, his assiduously built career has a small window: The Indian democracy.

Modi is stable in his seat of power because he is a democratically elected Prime Minister. He has 35 months to rule a shattered nation. All Indians know the expanse of the tragedy, intensity of grief and the trauma. People are visibly angry.

But, in India, time has been a great healer. During the Emergency, Indira Gandhi tried to throttle democracy. She lost election in March 1977 but within 33 months, the people of India voted her back in power.

The deep-rooted Indian democracy will give Modi a chance of his lifetime to keep the power and put it to good use in the coming three years. The rage among his political opposition is not enough to make his tenure politically unstable immediately.

Second, what Modi has in abundance is his determination and the resolve to win back the broken trust of his supporters. Time and again he has shown a compromising trait and the necessary flexibility to go for course correction. Fixing the economy will be his bigger challenge than emerging out of the COVID crisis.

Weakness

Whatever attempts Modi, his party and his ministers put in to pass the buck to the states for failing to handle the healthcare crisis, it is unlikely to pass muster because Modi has been strongly advocating “double engine ki Sarkar.”

In this terrible crisis if the BJP-ruled states including Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh would have shown exemplary models of the disaster management, it would have made a huge difference in Modi’s own standing in crisis.

As one COVID patient put it aptly, “System ne dum tod diya hai.” (The system has collapsed). It is also true that the non-BJP ruled states like Maharashtra and New Delhi have not been outstanding in the COVID management as cases and the death figures show.

BJP couldn’t put in place — for a full one month — dignified cremation of people. The party can’t easily escape its share of blame. In this unfolding humanitarian crisis, the deprivation of dignity of the dead has created deeper distresses than anything else.

What kind of governance is this where thousands of villagers are burying the dead bodies on the banks of Ganga for weeks and neither Lucknow nor New Delhi is aware of it? No authority stopped them.

Even the national media remained unaware of the burying of dead bodies for several weeks and it speaks volumes about the gap between rural and urban India.

The nature of the crisis is such that it will leave behind deep scars, bring in new social behaviours and leave many families poor due to hefty medical bills. BJP will face these issues and questions over and over again.

Modi and his government have to be accountable for the acts of omissions and commissions like allowing the Kumbh Mela, participating in election campaigns, not spending big money to buy ample stock of vaccines for its people.

Opportunity

Modi has once in a century opportunity, too. It’s a very difficult one but the opportunity does exist. He is likely to succeed and may turn it into advantage.

For Modi’s opponents it is astounding that by and large Modi’s core supporters are banking on him to bounce back. “Kya Modi virus laya?” that’s an often heard response when asked if the PM will lose his popular base.

Modi’s publicity machinery is also back in action after the initial shock. His biggest opportunity stems from the fact that Indian society is highly divided. COVID has hurt Modi but increasingly two distinct Indias have consolidated their respective views over the crisis and its management.

In today’s India, Modi’s critics and supporters live in their respective silos. They are actually comfortable in their own eco-chambers and talk only within it.

One set of people considers Modi and Amit Shah a threat to Indian democracy. Another set of people are not even interested in knowing what all Modi’s critics are talking about. Both sides have been victims of COVID-19, but India will soon see how their response widely differs on both — the pandemic and Modi.

The Prime Minister's political image could have been seriously affected if these “two silos” had some meaningful, civilised and frequent engagement. These exclusive thought-zones duelling with each other plays to Modi’s advantage.

Threat

There is real danger that the COVID-19 health crisis may not culminate into any big scale health infrastructure for poor people if politics ultimately overwhelms the discourse.

It’s not good for India and not good for Modi if shrill debate around nationalism and communal issues overshadow the urgency to build a modern health infrastructure in the country.