COVID-19 has a political significance

The BJP is clever enough to know the far-reaching political significance of coronavirus

On Sunday, India maintained a curfew as part of the war against COVID-19. Two days before, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had gone on air and addressed the nation on the topic of the virus that kills people no matter how well dressed they are and what their political ideology is.

If there is one lesson to be drawn, it is that globalisation — that process of mutual dependence of people in which the interests of companies and countries converge on product manufacture and delivery — has peaked. It had a good run, starting with the mid-1990s. The age of outsourcing is over.

If India wants to develop a vaccine against the virus, it will not be easy. The Indian pharma industry is dependent on Chinese imports to make medicines — the APIs (Active Pharma Ingredients) — come mostly from China.

It is not just pharma. The $30 billion (Dh110.2 billion) domestic smartphone market, among the world’s largest now, will see major disruptions as it is heavily dependent on imports. Modi has set his heart on solar power as an alternative fuel resource. Some 80 per cent of solar cells and modules are imported from China, whose trade exports to India are annually worth $70 billion. In the global scenario, China’s exports to the US are worth an estimated $1.9 trillion. It just means the virus is everywhere. Think of the stuff you ordered on Alibaba.

Politically, the virus is likely to be a good contagion for the right-wing across the world. As nations withdraw into their cells, populist themes like nationalism, patriotism and protectionism will rise.

That the virus broke out in Wuhan, Central China’s biggest industrial and financial city, is replete with symbolic significance. The disease exported, too, is truly global, killing 14,000 across the world and counting. In a recent speech, US President Donald Trump said there are problems that the US business faces because the ‘supply chain’ has been broken down. This is much the situation with economies around the world.

All which point to one thing. After COVID-19, humans could see themselves as one.

No man is an island entire of itself / Every man is a piece of the continent / A part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea / Europe is the less…, as John Donne said. Or, since political power is nothing if it does not behave as a means for safeguarding territory and the interests of the people inhabiting it, protectionism, as a backlash to globalisation and interdependence of capital, know-how and labour, would kick in.

In other words, more walls are likely to rise along borders, more detention centres will be built, more restrictions on travel will take place, and more things will be built and consumed internally, so the supply chain is not broken. We will learn to trust the other less.

In India, so far there have been more than 400 COVID-19 cases, and eight reported deaths. The national lockdown (curtailment of movement, ban on a gathering of over four people, closure of non-essential services) has been done with uncharacteristic rigour as exemplified on Sunday.

But COVID-19 demands a warlike discipline for weeks on end for it to be defeated. Indian businesses will be hurt. Already, the banking crisis and social polarisation is taking place. Buying and selling are naturally down. Even cinema houses have been shut. India without Bollywood. Who could have thought of that but COVID-19? It had to be a microbe to show a movie star his/her place.

Politically, the virus is likely to be a good contagion for the right-wing across the world. As nations withdraw into their cells, populist themes like nationalism, patriotism and protectionism will rise.

For a party like the BJP and for strongmen like Modi, a pandemic must play out to an advantage as the militarylike disciplinary measures required of the situation will be found more useful on all sides than differences of culture and independence of identity. Group identity politics that defines India’s liberal spectrum will find it hard to resist majoritarian ideology because arguments of survival in an emergency situation must supersede, in general, everything else.

In Delhi, last week, the direction of the process had clear vindication in the suspension of the sit-in at Shaheen Bagh, an epicentre of anti-CAA (interpreted as the largely discriminatory — against Muslims — Citizenship Amendment Act) movement. The protest, a health hazard, suspended itself on Sunday after three months of national attention with the Liberals promoting it as one of the greatest civil protests in post-independent India, and the Right Wing trolling it as anti-national.

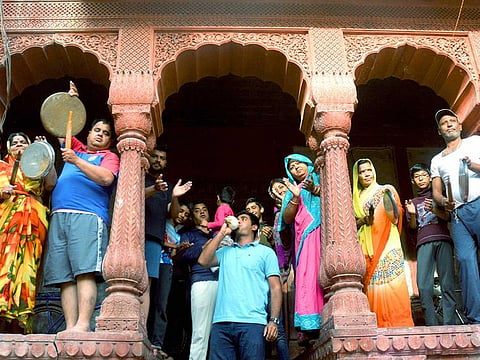

The BJP is clever enough to know the far-reaching political significance of the coronavirus. On Sunday, as Modi urged, around 5pm, Indians came out on their balconies and clapped and clanged plates and spoons in appreciation of the essential service workers out at large. It was emotional blackmail of sorts, but it worked.

Wisely, not once did Modi make mention of the movement in his national speech. Nor, as far as I know, has he ever asked the movement to be dispersed, probably because women and children are involved, and he would end up giving a handle to his enemies. In the event, there were critical noises from the Liberals themselves. Because, you see, good sense must prevail. The problem is precisely that good sense, on the whole, will tend to be increasingly nationalist and protectionist in the days during and after COVID-19.

The short term goal of India’s fight against the virus, indicating as it does the ‘ills’ of globalisation, as in all other countries, would be containment and survival. But in the long term, India is likely to see the intensification of the ‘otherising’ of things that have in them the potential to be seen as alien.

The next one month or so will, in fact, be an emergency situation for 1.3 billion Indians. Unlike the 1975 national emergency that extended for 19 months under the Indira Gandhi government, there is now a critical mass of middle class aspiring for order and national pride. The BJP is clever enough to know the far-reaching political significance of the coronavirus.

On Sunday, as Modi urged, around 5pm, Indians (including this writer) came out on their balconies and clapped and clanged plates and spoons in appreciation of the essential service workers out at large. It was emotional blackmail of sorts, but it worked. India was united briefly even if it meant making more noise.

In the weeks and months to come, India is set, more than ever, on a unificatory political process, of gestures and tokens that will add up to a mutant policy militating against diversity. And fundamentally it would make sense. But did man ever live by sense alone?

— C.P. Surendran is a senior journalist based in India