Moulded by memories

‘To Kill a Mockingbird' is a deep representation of Harper Lee's life

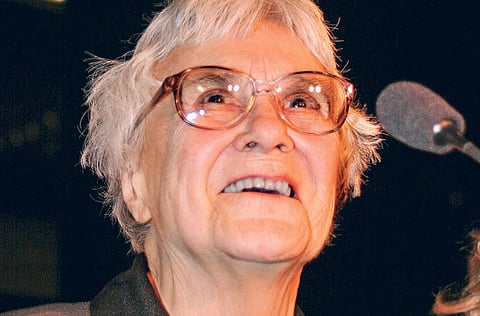

Despite the thick, black sunglasses, there is something familiar about the frail 84-year-old woman, as she is helped falteringly towards the lake shore. A delighted smile flickers across her face as ducks and Canada geese flock around to feed on the scraps of bread brought from the care home where she lives in a modest apartment.

Dressed in a clean but faded T-shirt and loosely fitting slacks, she attracts barely a glance from passers-by. Yet hers is the face which has stared from the cover of a book that has hypnotised more than 40 million readers around the world.

Single story

She is Harper Lee, whose only book, To Kill a Mockingbird, won the Pulitzer Prize, is translated into nearly 50 languages and was turned into the Oscar-winning 1962 film starring Gregory Peck. It also made Harper into a multimillionairess. Nervously, I approach the novelist, carrying the best box of chocolates I could find in the small Alabama town of Monroeville, a Hershey's selection. I start to apologise that I hadn't brought more but a beaming Nelle —as her friends and family call her — extends her hand.

"Thank you," she told me. "You are most kind. We're going to feed the ducks but call me the next time you are here. We have a lot of history here. You will enjoy it."

It was the most fleeting of conversations but that is hardly surprising. Harper has said precious little in public since the publication of Mockingbird 50 years ago. She has written nothing else since, save a few short stories in the Sixties.

Indeed, she has spent the past five decades living in almost total seclusion. Even when she travelled to the White House to receive an award from former US president George W. Bush three years ago, she did so under the strict condition that she would answer no questions and make no acceptance speech.

Nobody knows what she does with her wealth. Her friends say material goods are unimportant to her and that if she gives to charity, she does so anonymously. For much of the past 50 years, she has shunned the formality and racism of her native Alabama to make her home in a tiny flat on Manhattan's Upper East Side.

Years of silence

Only now, towards the end of her days, has Harper returned to live in a sheltered housing complex in her childhood hometown of Monroeville. I went to Alabama in an attempt to answer the great mystery of why she should have spent almost half a century in silence. Her friends agree to introduce me to her on one condition: that I make no mention of The Book, as people here refer to it.

Based on a few gnomic utterances over the years, many literary commentators have attributed Harper's solitary life and subsequent failure to publish another book to her alarm at the tidal wave of praise for her Mockingbird, in which the racial bigotry of the South is witnessed through the eyes of a little girl, Scout.

Others have suggested that perhaps she only had one great book in her and that she knew that every subsequent attempt would be regarded as a disappointment.

But according to confidants, many of whom have known her since childhood, what Harper has really found a burden is her enduring sadness about the book's under-lying themes.

Painful secrets

They say that while To Kill a Mockingbird is ostensibly a courtroom thriller in which Scout's compassionate and principled lawyer father Atticus Finch defends a black man falsely accused of assaulting a white woman, Harper drew on deeply painful family secrets to create her protagonists.

Furthermore, her liberal views on race were extremely unpopular in her native Deep South. Indeed, many in her own family were unhappy with the tone of her book.

"I'm not a psychologist but there's a lot of Nelle in that book," said 87-year-old George Thomas Jones, a retired businessman who has known Harper and her family since she was a girl. "People say the publicity the book got turned her into a recluse but publicity didn't ruin her life: I don't think Nelle's ever been a real happy person."

Jones said Harper's father, Amasa Coleman Lee, a former newspaper editor, lawyer and state senator who was clearly the model for Atticus Finch, was a real genteel man, who listened more than he talked but didn't show much affection.

"I used to caddy for him on the local golf course. He was so formal that he would wear a heavy three-piece suit, a shirt, a tie and stout shoes to play golf, even in the heat of the summer."

In an episode that foreshadows the compassionate and fiercely moral hero Atticus, played by Gregory Peck in the movie, Harper's father had defended two black men charged with murder in a celebrated case in 1919. After they were convicted and hanged, he never practised again. But unlike the fictional Finch, Lee was a staunch segregationist who supported the harsh Jim Crow laws of the American South.

In the novel, Scout lives in fear of a malevolent phantom, a psychologically disturbed neighbour called Boo Radley, who ultimately saves her life. While it is clear that the character is in part based on a reclusive neighbour, in reality, it was Harper's mother Frances who was the source of much terror and unhappiness.

Suffering from depression and violent mood swings, friends in the close-knit Alabama town say that Frances allegedly twice tried to drown her daughter in the bath. As a result, perhaps, the young Harper was regarded as a difficult and aggressive child who would think nothing of punching other children who annoyed her.

On the defensive

Jones said: "Nelle was always on the defensive when she was a little girl. The book didn't make matters any better. People recognised it was based on her life. My late wife was her golfing partner and she knew never to ask her about it. It's not just something she didn't want to talk about, it was a subject you wouldn't want to touch with a ten-foot pole.

"Nelle is not lonely. This is the life she has chosen to lead. She could afford better but maybe this is what makes her feel safe after a life starved of affection."

Harper's older sister, Alice, 98, is close to Harper and helps handle her financial affairs. I asked whether her sister ever regretted writing the book. "I don't think she has any regrets," Alice replied with a frown. "But we talk about the book only in relation to business."