Tom Wolfe was lucky. His passing will have allowed him to just miss out on the shower of celebrations for the centenary of the Bauhaus. In From Bauhaus to Our House (1981) the US author had written a ferocious outcry against the devotees of the famous German art school, held responsible for the concrete cubes at Sarcelles, New York or La Défense. And at the forefront of those accused, its founder, a certain Walter Gropius who Tom Wolfe nicknamed “Prince of Silver” or “White God no. 1”. As strange as it may be, the first months after opening in Weimar in April 1919, the Bauhaus school showed a rare talent for attracting enemies. To such an extent that a newspaper launched a call to residents of the town to close it down. For fourteen years of its existence, the Bauhaus was just as much contested as persecuted. But, why so much hatred?

Partying is an art

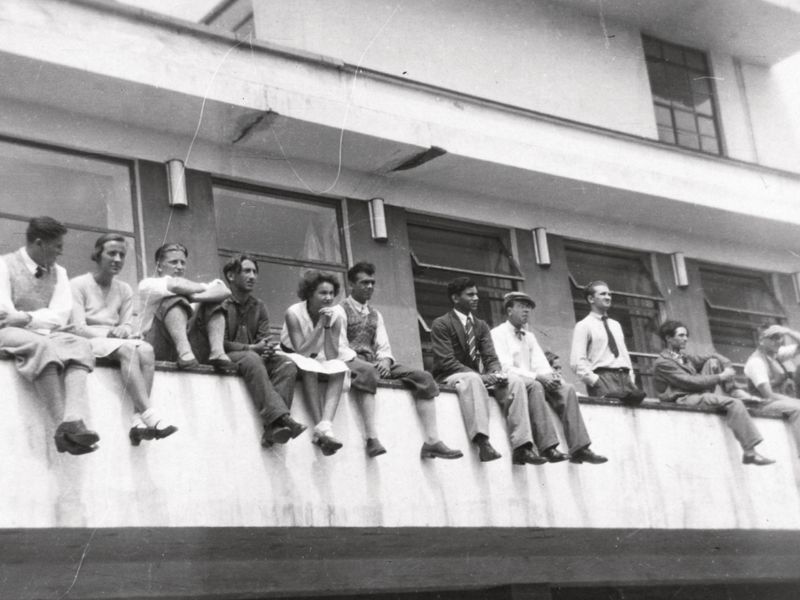

According to Walter Gropius, the learning was simply intended to remove barriers to the arts. It was necessary to “return to artisanal work, because there is no professional art” stated the Austrian architect as a slogan. On the programme of his manifesto: theatre, conferences, poetry, music, traditional festivals. And this wonderful deep name, Bau meaning “construction”, Haus meaning “home”. The new emblem of perpendicular puritanism. Students lived and ate together, shared in sports and leisure activities. Oh yes, Gropius also insisted on a fact: no difference between men and women. The distracting ceremony of the ravaging institution did not manage to convince the new local power. The Bauhaus was chased out of Weimar to take up shop in Dessau. On 4th December 1926, a thousand guests were invited to a large party to inaugurate the new building designed by Gropius. The party would be the strong point of the new institution. “Tell me how you party and I will tell you who you are.” This was the motto of Oskar Schlemmer, artist, choreographer and master of ceremonies of the Bauhaus who had the mission of creating an experimental theatre. And so, the social evenings at the school, organised to the most minute detail by Schlemmer and his theatrical workshop pupils, made the renown of the Bauhaus just as much as its teaching. “From the first day of existence of the Bauhaus, he stated, the stage was present, as from the first day, the urge was already there. It expressed itself in our exuberant evenings, in improvisations and in the imaginative masks and costumes we made.” He dressed dancers in abstract costumes, with geometric forms such as for the famous Triadic Ballet participating in a reflection on the relations between man and machine. The teachings of dance became so important to be worthy of the status of “Bauhäuslers” that Walter Gropius called on an eminent dance teacher from Berlin. Out of his desire to integrate with pupils, he imposed on teachers and himself intensive classes so as to master the techniques of the Charleston. A requirement which made two famous teachers at the school quite mad, Paul Klee and Vassily Kandinsky!

A haven for subversion

For the Bauhaus, partying became an art form. And any occasion was acceptable. Birthdays of the work-shop teachers or the arrival of a prestigious guest. These naively and healthy parties would soon draw in the whole of Dessau where the young elite from Berlin were seeking thrills. There was the Beard, Nose and Heart Festival where moulds of noses, hair warts and all were on the bill. To conjure up the quotation by Goethe, “architecture, this motionless music”, an orchestra would be assembled to accompany these night owls. But merely reducing them to a jazz band would be offensive. A bedlam of chairs, gunshots, manual bells, giant tuning forks, sirens, pianos made using iron and nails, and cries of Sioux would lead the ball. We can also mention the White Festival (1926) with its dress code of “2/3 white, 1/3 colour” and to promise the “emotional, exciting and normal” via stripes, polka dots or checkers. The most legendary night of all would be the Metal Festival (1929) of which the invite was made of sheet metal and which suggested that gentlemen arrive as egg whisks, pepper mills or tin openers.

And women decorated with balls and chains should be accompanied by a “radioactive substance”. Guests arrived in a slide into the large hall covered in iron from the ground to the ceiling. This was so reminiscent of the décor of Andy Warhol’s Factory, covered in aluminium foil. The sheer renown of these parties became a sort of barometer of the Bauhaus, and Schlemmer began to wonder whether they had not sparked some sort of “hatred and passion”. You could be forgiven for wondering whether these uncontrollable moments of debauchery contributed towards the name of “house of Jewish-Bolshevik subversion” as given by the Nazis who decided to definitively close the Dessau school in 1933. However, as well as its sense of partying, things were spoilt: the Bauhaus had imposed a new basis of reflection as to design and modern architecture. This small group of artisans had produced, for six years, the most influential objects of all time. In the years following its closure, Walter Gropius and the last director of the school Mies van der Rohe attempted to gain the good grace of the new Reich by proposing several architectural projects. However, the day when Hitler trampled on one of these models for an international expo pavilion, it was high time to emigrate. And so came the time to take stock.

Upon opening of the school, there were more girls than boys. Unfortunately, this new collective guild of artisans founded by Walter Gropius had several medieval reflexes. These young girls with geometric haircuts, who followed vegetarian diets, were confined to the weaving workshop, and infinitely few had access to architecture classes. Indeed Gropius sincerely believed that women thought in two dimensions and that only men could manage three. Marianne Brandt was an exception. She entered the metal workshop and was one of the very few ladies to have made a name for herself at the Bauhaus (the others had to wait to leave the school or emigrate). Her Kandem bedside lamp, created in 1926, was one of the very profitable creations made by students and its pure lines still haunt our lighting shelves today. This is also the case for many other student creations which are still in existence at Habitat or Ikea.

Amongst the many students and teachers to flee Germany in the thirties, some would be responsible for building close to four thousand Bauhaus style buildings in Tel Aviv. And legions would come to build in the USA up until the seventies. Amongst the former students to not have emigrated, some would die in extermination camps. In recent years, historians have also highlighted the scandalous background of some Bauhaus students, an institution often shown in a simplistic manner as a symbol of resistance. This memorial work would deserve to benefit from the centenary to remind people that some of the former students entered the ranks of the Third Reich so as to design propaganda posters. Or, more chilling still, as Fritz Ertl who became an officer of the Waffen-SS, who would design the barracks and crematoriums at Auschwitz. A certain Ehrlich even practiced his learnings of the typography of the Bauhaus to decorate the iron gates at the Buchenwald camp, just one hundred and sixty kilometres from Dessau

A glass of iced water in the face

After closure of the school, the building was used as a training centre for Nazi Gauleiter (governors). It was then used as a hospital and driving school before complete restoration.

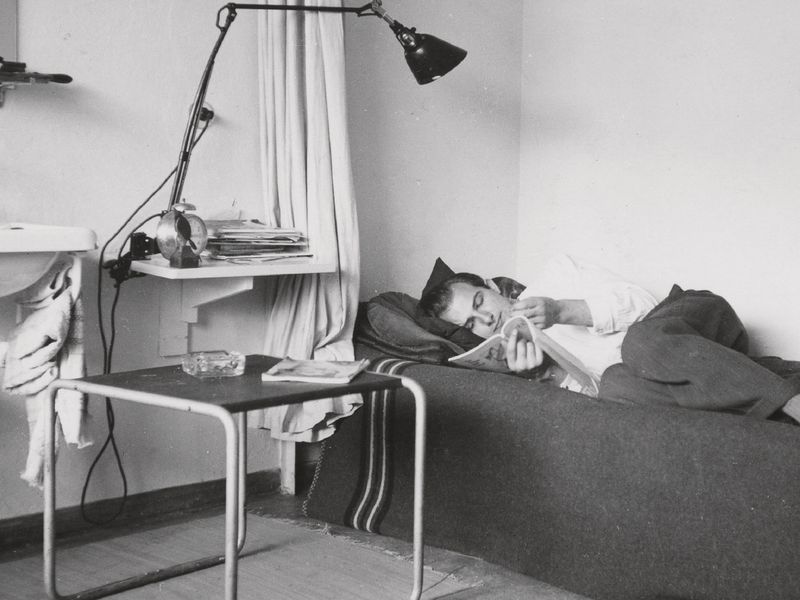

It is now possible to spend the night in one of the thirty original rooms for the price of a stay in a motel. With its tube lighting, tubular chairs and blood red lino, these large modernist cells are somewhat reminiscent of the charm of East-German youth hostels. It has, above all, become an infinitely calm location compared to the brimming and bustling period of the Bauhäuslers. There is no longer a risk of being awaken in the middle of the night by the cavalcades in the floors, students climbing the façade of your balcony and the cries of those dancing on the roof. You will simply live an “authentic” experience, one of those sweet and dizzying nostalgic moments. To receive, wrote Tom Wolfe, “this glass of iced water in the face, this tonic slap, this bloody reminder of our bourgeois soul which we call modern architecture”.