Wayl: the story of the UAE’s first English superhero comic book

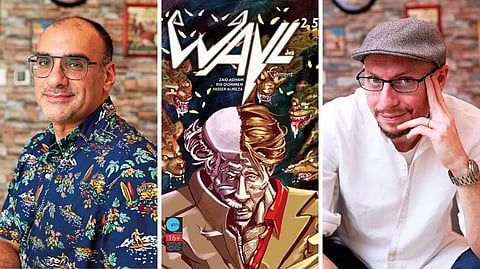

The writer-illustrator team behind what is possibly the country’s first English graphic novel tells Shreeja Ravindranathan about battling funding issues and a dearth of publishers

It’s not until the end of my conversation with Zaid Aladham and Yasser Alireza – the creators of comic book series Wayl (Arabic for woe), the Middle East’s first psycho-thriller comic book series – that we address a thorny issue: The ignominy comic books sometimes suffer of being a low-brow format, a childish hobby that critics think full-grown adults shouldn’t be dedicating their time to.

I’ve braced myself for some impassioned verbal kapows. Instead the writer-illustrator duo offer a rebuttal rooted in facts and figures – Alan Moore’s watershed graphic novel Watchmen has been declared one of the greatest novels of the 20th century. French-Iranian novelist Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Persepolis’s animated film adaptation bagged an Oscar-nomination and film festivals despite its simplicity and childlike innocence. The examples of the value of comics are numerous.

‘Adults do see a value in comics, it’s just their understanding of what comics are that’s wrong,’ elaborates Yasser, Wayl’s illustrator. ‘A lot of people think it’s just about the superhero. But even superhero comics have some really enriched stories. Some have entertainment value, some have social value, but they all contain intellectual value. There’s a story for everyone in comics no matter how old you are.’

And that effectively sums up the intent behind creating Wayl – the format’s accessibility and the universality of its appeal. It is why periodical comics and graphic novels brought in sales worth $1.09 billion (about Dh4 billion) in the US and Canadian market alone in 2018, according to trade news sites ICv2 and Comichron.

While there are no definite statistics on the sales of comic books in the Middle East, we only need to look around to recognise the impact of the sequential art form on the region – around 60,000 people attended MEFCC in 2019 and geeky cons have popped up around the region and found a foothold in other GCC countries, such as Saudi Arabia’s Comic Con Arabia. Children’s magazines such as Majid, Samir from Egypt and the Arabic version of Tintin have been staple reads for Arab children who grew up in the 80s and 90s, points out Zaid. And it’s this appreciation they’ve carried on into adulthood.

Wayl embodies social value by allowing its gritty narrative to dissect and illustrate the fallout of crime, greed, corruption and misuse of power. The arresting artwork and action-packed storyline checks off the entertainment box, and the combination of the two with a complex narrative gives it intellectual worth – the six-part comic series charts the transformation of Sufyan El Taher, an heir to a Jordanian construction empire, into the super-being Wayl.

When Sufyan returns to Amman after his father’s death to take over the family business, he’s left for dead at the High Place of Sacrifice in Petra by his father’s scheming manager. Sufyan is healed by the mystical ancient place and acquires powers.

As for the creators, Jordanian national Zaid and Saudi national Yasser are eloquent, gainfully employed and fathers to boot, toppling broad stereotypes of comic fans that paint them as infantilised geeks.

But like every good superhero comic we need to back up to their origin story to make sense of how a brand learning director and a visual communications manager teamed up to create the first English-language comic from the UAE featuring a home-grown Arab superhero.

Origin story

When the first Middle East Film and Comic Con was announced in 2012, it got Zaid wondering: If the region had a comic fanbase large enough to have its very own convention, why were there no home-grown superhero comics in English to back it up?

Not that there has been a complete dearth of attempts by Arab authors in the region to enter the superhero market. Take Kuwait-based Teshkeel Comics’ The 99, launched in 2006 to great fanfare but was discontinued in 2013. Or Malaak, the Angel of Peace by Lebanese author Joumana Medlej, and featuring a female superhero – it had a print and web run from 2006-2015. The Chronicles of Shamal in 2016 by Bahrain-based South African author Anna Thackeray is another one.

So Zaid decided to throw his hat into the ring. He set about brainstorming with two local illustrators to flesh out the concept of Wayl into concrete visuals that then won MEFCC’s Best Original Artwork award in 2012. That win gave Zaid the encouragement he needed to double-down and finish the script for the first two issues.

Meanwhile, in a parallel narrative, Yasser, who had moved from Saudi to the UAE in 2010, won a competition held by MEFCC and Museum of Moving Images in 2014 and bagged a 20-minute-meeting with CB Cebulski, the editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics.

The two only met in 2015 when Zaid decided to visit Kinokuniya to do some R&D and figure out if a comic book would do well in the UAE. ‘When I get there, I see a lovely character scratching his head, dressed in a Flash T-shirt, who seems like my target demographic, and get chatting,’ Zaid describes.

That ‘lovely’ character was Yasser, who would then go on to become Wayl’s illustrator and Zaid’s partner in creative crime. ‘It’s hard to sum up the journey of how we got to doing what we do today in a linear manner. We’re not just pigeonholed into what you see us doing,’ Yasser says. And it’s true; dabbling in a multitude of creative industries individually – Zaid worked in television as a director, and then marketing, Yasser moved from advertising to heading a local arts and culture magazine in Saudi Arabia as an interim editor-in-chief to publishing a book about prose and short stories about social life in Saudi Arabia called Collision KSA – they’ve both changed professional hats a lot.

Their childhoods, although spent in different countries (Zaid grew up in the UAE and Yasser in Saudi) too are a labyrinth of creative pursuits, whether it’s Zaid’s stabs at prose, poetry and a heavy metal band or Yasser drawing entire comic strips in the back pages of his maths books and minoring in theatre; there’s a mutual love for storytelling that stood the test of time and the demands of real life to distil into Wayl.

‘One of the important bastions of our life is being able to spin a good yarn,’ Zaid sums up.

Even if it means juggling full-time jobs, creative slumps and self-publishing by dipping into their savings. ‘We’re still in an environment that doesn’t foster comic books as a career,’ says Zaid of not just the region’s publishing industry that is hesitant to invest in the genre, but also culturally. Both Zaid and Yasser’s families were concerned about how their backgrounds in visual communications and a love for the arts could translate into bankable careers.

‘And while it’s difficult anywhere in the world, there’s extra layers to that challenge here,’ adds Yasser.

Storytelling obstacles

For Wayl, one of the main challenges was sidestepping the Arabian Nights-esque stereotypes Middle Eastern characters are sometimes assigned in mainstream media, such as the formulaic myth of the jinn or the Arabian nomad trope – Marvel’s scimitar-wielding Arabian Knight comes to mind. Instead, the creators have chosen to consciously root Sufyan in the living and breathing city of Amman. Even their villain Abu Shakoosh is based on an actual unidentified hammer-wielding serial killer of the same name who bludgeoned pharmacists and terrorised Amman in the mid-90s. Jordan’s very own Jack The Ripper.

So far they’ve done well, with readers telling them their setting feels authentic. ‘Our foreign readers have told us it gives them a deeper understanding of what’s going on in the region and Arab readers have told us that we’ve been able to capture the essence of the society we live in. That they’ve all met characters without moral compasses from the series in their real lives,’ Yasser says. It’s a personal triumph for Yasser and a testament to his artistry that although he has never visited Amman he has managed to recreate the soul and ambiance of the city on paper through Zaid’s memories of his hometown, and make it a character, ‘the glue that holds the whole series together’.

Perfect chemistry

It’s also a testament to the pair’s chemistry as writer and illustrator. Both their personalities and literary tastes are diametric opposites – the Roald Dahl and Stephen King-loving Zaid is succinct, philosophical and saturnine, even ‘morbid’ to quote his own words (‘I wrote an entire novel titled Return of Death aged nine’), while Disney fan Yasser is garrulous and expressive as he chirpily describes how the animated series Woody Woodpecker and Garfield are his favourites. But the pair share a synergy and trust that’s anything but a grudging compromise. It has helped them tango through sticky situations without blame games, like when the first issue didn’t stick the landing visually because of a confusing action sequence.

‘You need that ying-yang, opposing point of views,’ Yasser explains, but ‘we’re mature and know what’s important is what serves the story, not our egos,’ says Zaid.

It is easy to draw parallels between Wayl’s protagonist Sufyan, a reluctant businessman-turned-vigilante super being Wayl, and the original vigilante superhero of comics – Bruce Wayne/Batman. There is also the common denominator of the manic villain: Abu Shakoosh could make the Joker sit up and pay attention. And the creators make no bones about making Wayl feel stylistically familiar to established comics such as Batman, which in fact is Zaid’s favourite, and The Joker and Gordon of Gotham’s raw, edgy, heavy-on-ink style art was the concept art he gave Yasser for Wayl. But Wayl aspires to go beyond such reductive comparisons. Yasser and Zaid say the idea is to show readers that seedy underbellies and amoral people are universal and they aim to deconstruct what these grey areas look like in the Middle East, a region that functions on a strong code of right and wrong. ‘We’re talking about this as a secular social issue, not a geo-political or religious matter,’ Zaid clarifies.

Wayl himself grapples with right and wrong. Yasser and Zaid unanimously agree that he’s more a superbeing who’s coming to terms with his powers and responsibilities as opposed to a superhero. He’s still learning to walk the fine line between vengeance and meting out justice.

Which means he’s more X-Men than Batman, I ask? ‘Definitely!’ Yasser laughs. ‘He’s constantly going through some existential crisis.’

Diversity

It was a crisis of identity on Yasser’s part, though, that determined Wayl would be characterised as a person of colour, not a bid to match paces with mainstream comic franchises where inclusion is the buzzword – in 2013, the fictional Pakistani-American character Kamala Khan aka Ms.Marvel became Marvel’s first Muslim superhero, and early this year Marvel announced its first Asian superhero movie and the cast of The Eternals is said to be the most diverse superhero film cast. DC Comics opted to make Hawaiian actor Jason Momoa Aquaman instead of the traditional Caucasian interpretation.

‘With diversity the idea is not to say, ‘here is a brown Arab superhero, hurray!,’ Yasser, who is mixed-race, explains. The Pakistani-Saudi illustrator was adamant that Wayl be brown, so Arabs of every ethnicity could relate to a super-being and celebrate the way they look. ‘Every time I tried to show the average GCC national who is brown or black in advertising or art, I got pushback. Both Zaid and I have been minorities depending on what part of the world we’ve been in, so we know how important it is to acknowledge people who have no mainstream representation.’

It’s also why Sufyan’s wife Sophia is half native Canadian: ‘She represents the experience of white women around the world who are married to minorities. It’s a valid experience and we want to portray them without resorting to clichés.’

Aspiring to cosplay fame

While Zaid and Yasser prefer not to bang on drums about their protagonists’ racial appearance, they’re always pumped up about the support they get from readers.

Zaid, who was tight-lipped during the diversity discussion, comes to life while describing an action figure mock-up of Wayl a fan sent them, meticulously capturing all the design elements including the W-shaped lightning scar on his back. ‘They worked on it for a year,’ Zaid gushes.

They’d love to see Wayl soar into the echelons of fame where someone would one day cosplay him, but for now these little victories along with the messages and comments fans leave them are the ‘fuel and tinder that keeps them going.’

Not to mention support from the UAE’s National Media Council, the Sharjah Book Fair and MEFCC, where they’ve conducted workshops, and the Emirates Literature Festival, where they’ve been panellists alongside Nigerian-American writer Nnedi Okorafor (Star Wars Anthology and the new Black Panther comic book), and Chilean comic book artist Gabriel Rodriguez. Any misgivings they had about their purpose in life was put to rest by feedback from their idols – while CB Cebulski’s praise fortified Yasser’s conviction that comics were his calling, Zaid received affirmation from Sergio Aragones, the Spanish/Mexican cartoonist and writer famous for his contributions to Mad magazine, when they met at the San Diego Comic Con in 2016. ‘I had tears gushing down my face when my all-time hero flipped through the first issue of Wayl and told me “I think you’re going somewhere with this”.’

What’s next?

Wayl is now going towards becoming a condensed graphic novel that will feature the complete 11-chapter story arc of the first series, including six chapters of the main arc and the five chapters of a sub-series titled Figment that’s illustrated by artist Ria Oommen, and will release in 2021.

The decision has been driven by a lack of funding and it’s the only way Zaid and Yasser can ensure fans get to read the entire story as it was envisioned without throwing in the towel. When you get down to brass tacks, passion needs to result in profits too, says Yasser.

‘There is a market for comic books. But no marketers. We do have some really good friends at Kinokuniya, Comic Stop, Virgin and Comic Cave, who’ve been really supportive in carrying our books – we sold 1,600 copies totally: 900 of issue 1 over three editions, 500 of issue 2, and 200 of issue 3. But pushing publishers other than DC and Marvel is tough. It’s tough abroad too, so in a small market like here, people are throwing their investment into what I guess they know best.’

Although international publishers have shown interest (international publications such as the LA Times for instance have given Wayl column inches), Yasser and Zaid don’t want to ride to success on the coattails of the West: We’re trying to find a way to make this come from the region to the rest of the world,’ Zaid says.

‘We don’t want to be another Arab story that’s successful from the outside-in.’

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox