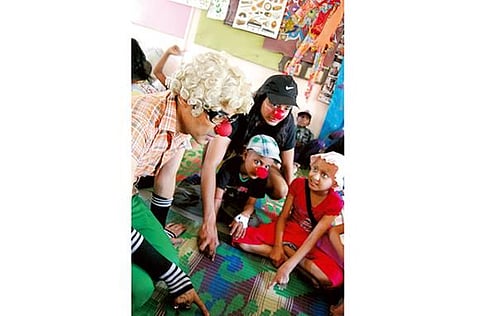

Bring on the caring clowns

Laughter really is the best medicine as these clowns visiting children in hospitals prove

When the doors at the end of the corridor swing open, a man wearing a check shirt, curly white wig and red nose bursts through. He spots Nikhil, a six-year-old boy, and goes to shake his hand. The youngster must be stronger than he looks because the man starts squirming, complaining that his fingers are being squashed, and then hops around clutching his hand in mock pain.

Nikhil, who is battling leukaemia, starts giggling. It’s an infectious sound, and soon other children start to peer out of the rooms lining the corridor. Within moments the kids aged between four and 15, who had until then been lonely, bored, sad, or scared, join in the laughter. The man is delighted – that’s exactly what he planned to do. After all that’s his job.

Ashwath Bhatt, a medical clown, has just entered the paediatric oncology ward at the All Indian Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS), a New Delhi hospital, to cheer up the children battling a myriad cancers. It’s just one of three hospitals in the city that he and three of his colleagues visit every week to get the children to forget their pain and laugh for a couple of hours.

‘It has been scientifically established that clowning helps people – adults and children – to cope better with their conditions or illnesses,’ says Ashwath. ‘It also helps people suffering from depression and stress.’

A professional actor based in New Delhi, Ashwath, 39, uses clowning as a way of helping people deal with trauma, grief and pain in hospital. One of a tiny band of similar joy-spreading clowns that are dotted across the country, he is a rare Indian example of the ‘Medical Clowning’ movement that has been gathering pace around the world since the mid-1980s.

‘The transformation among patients and their families when we are clowning around is truly incredible,’ he says. That’s why he asked Diya Banerjee, an Indian film-maker, to make a documentary on clowning. Set in a children’s cancer ward in New Delhi’s AIIMS, The Hope Doctors shows what a difference the clowns make to the patients and their recovery.

Medical Clowning has a surprisingly long history – while the old adage ‘laughter is the best medicine’ has been around since at least the Middle Ages, more recently pictures from around 1900 show a French clowning troupe doing acrobatics in a children’s hospital.

Known as therapeutic clowns or medical clowns, these funny men and women use techniques such as magic, storytelling and other jesting skills to empower children to deal with the range of emotions, such as fear, pain, anxiety and boredom, that they may experience while undergoing treatment in hospital.

Clowns can encourage patients to do their physio exercises, use fun and games to take patients’ minds off what is happening during awkward or painful examinations, and help patients and their families maintain a positive state of mind during what may well be the most difficult phase of their lives.

Though Medical Clowning is not common in the UAE, it nonetheless exists. A group called Clowns Who Care bring hope and joy to a number of places where their cheerful daftness is hugely appreciated. ‘In the UAE we mostly work at the Senses medical and rehabilitation centre for children with special needs,’ says the group’s founder, Mina Liccione, who began Clowns Who Care in 2010. ‘My mentor told me that the purpose of Medical Clowning is to help the kids to remember the laughter more than the pain,’ she says.

Last year, Mina went to visit a six-year-old boy in a cancer ward. She’d been warned that he was very shy and might not want her in his room, so Mina thought she’d try something different: she dashed past his room at lightning speed. Then she passed at a slightly slower pace and made eye contact. The third pass was done super-slowly: when the boy made eye contact Mina ran away, pretending to be scared. ‘It made him giggle,’ says Mina, ‘so I did it again – and this time his Mum came to the door and told me to come in. I said, “I’m too shy. What if he doesn’t like me?’’’

When the boy shouted back, ‘I’m not scary, come here!’ the connection was made, and within moments he was wearing her clown nose, laughing and learning how to spin plates – one of Mina’s best tricks.

Child psychiatrist and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, Dr Arlette Lefebvre is one of the hundreds of experts who vouches for the benefits of medical clowns. She says clowns provide children with a sense of control over their environment, helping them cope with the physical and emotional stress of being in hospital. ‘My experience has been very positive with clowns. They enable children to feel more comfortable and less scared and that’s an important factor in recovery.’

Today, Medical Clowning is a paid (though not necessarily staff) position at a number of hospitals around the world including Alberta Children’s Hospital in Canada and The Meyer Children’s Hospital in Florence, Italy.

From Brazil to Australia to the Netherlands, there are organisations that connect hospitals with clowns to help with patients and their family. In France, an organisation called Le Rire Médecin has almost 100 professional Medical Clowns working across the country. In the US, the Medical Clowns of Big Apple Circus Clown Care unit make 225,000 patient visits a year.

Though there are an estimated 5,000 Medical Clowns in the world, it is still in its infancy.

‘I use my clowning experience to engage with children and distract them from their everyday medical scenarios,’ says Ashwath, who has appeared in some Hindi movies including the Shahid Kapoor hit Haider.

Fif, who was previously on staff as a therapeutic clown for Alberta Health Services in Canada, is currently working with a number of hospitals near Puducherry and is in conversation to potentially collaborate on a project to train medical clowns in India. ‘A huge part of medical clowning is distraction therapy,’ she says. ‘You are trained to work closely with a medical team. So, if for instance a child is undergoing a painful procedure like a spinal tap, the clown can help distract the child with his antics and magic while the doctor performs the procedure. It also humanises the hospital environment and lowers stress levels of children undergoing treatment.’

Humour works, she says, because it empowers people.

‘When patients are frustrated with the medical staff, the clown can lighten things up and bridge the gap,’ she says, citing the time a five-year-old girl, Ritu, who was suffering from a severe stomach condition, refused to take her medication in hospital. The child was getting weaker and her condition wasn’t improving as much as the doctors had hoped.

‘No amount of cajoling, including from me, the clown, helped,’ says Fif. But one day she went in to see the child and started playing with a toy sheep on her bed. Soon, the sheep was climbing up the hill (Fif’s arm, neck and head), and when it got to the summit Fif let out a loud rasping sound. “The little girl shrieked with gales of laughter,” recalls Fif, smiling at the memory. The ice was broken and the girl wanted the sheep to climb on everyone’s head.

Fif grabbed the girl’s doctor, got him in on the act, and once the bridge was built, and the girl was ‘in charge,’ says Fif, ‘she started to take her medication.

‘Hundreds of scientific and anecdotal studies strongly suggest that laughter helps with certain types of illnesses,’ she says. That’s a serious reason to bring on the caring clowns into more hospitals around the world.