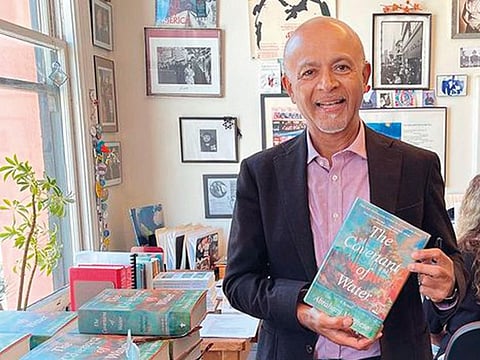

Abraham Verghese shares how he wrote the bestselling The Covenant of Water

Oprah Winfrey said The Covenant of Water is one of the top 3 books she has ever read

I was sitting at this desk when I got the call,’ says Dr Abraham Verghese, his calm and composed voice stressing just a tad on ‘this’. He pushes back his swivel chair to indicate his writing desk that sits in his tastefully decorated study. A bookshelf stands in the background while the wall on his right holds up a large white board that is covered with jottings, squiggles, little cartoons and pointers (we’ll come to that later).

I am on a video call with the author/doctor who is in his home in California, US, to talk about his recent book The Covenant of Water that is taking the writing world by storm, and the call he is referring to is the one he received from Oprah Winfrey on March 30 this year– a call that got him quite literally to his knees.

He admits that he initially didn’t quite believe that she would be calling him. ‘You know, it was just a couple of days before April 1st,’ says Abraham, with a smile.

Later, in a video that has now gone viral, the acclaimed author and doctor, who is also professor at Stanford University School of Medicine, can be seen telling the American publisher, television producer and talk show host behind her eponymous book club that the first thing he did when he received her call ‘was to stand up’ clearly unable to believe his ears, before ‘I went down on my knees at the end of the call’.

Oprah, on her part, recalls welling up with joy on the call with Abraham. ‘He teared up and I teared up and we were both crying on the call,’ she says. ‘This has never happened to me. Ever.’

Unstinting in her praise for the book, she gushes how reading The Covenant of Water ‘transported [me to] a different land. I was humbled that someone could have a mastery of words like the way Dr Verghese does.’

In the video she can be seen squeezing his palm in delight as she praises him for his ‘incredible gift’ of being able ‘to use words to put people in a different place in their mind and in their spirit’.

Oprah, of course, is not the only one who has been overwhelmed by the book that spans three generations and tells the story of a south Indian family that appears to be suffering from a strange affliction. The family terms it The Condition, others a curse, some, fate where in every generation, at least one person of the family dies by drowning.

Spanning more than seven decades, the story is epic in its scope and lyrical in its detailing. Abraham paints a brilliant tapestry of the 1900s, depicting a bygone India in a tale that ebbs and flows with stories of its peoples and of the times. A tale of love, faith, beliefs and medicine, it lays bare the lives and secrets of a Malayali family – and of a few English and western people who were residents of South India at the time.

If there is a single character that holds the thread of the story it is Big Ammachi, literally translated as Big Mother, a matriarch who is married off when in her early teens to a man 30 years her senior.

At once moving and heart-warming, poignant and nostalgic, the novel transports the reader to a nostalgic world on delightful waves of literary brilliance.

While The Guardian termed it ‘splendid [and] enthralling’ and a ‘riveting and sprawling epic’ (at 700-odd pages it weighs a little over 2 pounds), the New York Times praised it as ‘a healing feat of imagination, a whole world to get lost in’.

At one point of the writing, the author recalls how he himself almost got lost in his story.

‘You see this white board here?’ he says, pointing to the wall holding up the board. ‘Although I had the plot mapped out on it I could never seem to keep up with it; the writing takes on its own direction once the characters get formed. So I had to keep up with where I was in the narrative on the page.’

Abraham, who tends to think visually, wanted to have a blueprint of the story before he launched into the book. ‘But the blueprint kept changing so there were many, many iterations to my board,’ he says with a laugh.

What led him to write this book?

‘After my first novel, I was looking around for a subject for another; I wasn’t in any hurry, though,’ says the award-winning author.

Abraham’s debut novel Cutting For Stone is set in Ethiopia and the US, and tells a moving and emotional tale of twin brothers orphaned after their mother’s death and father’s disappearance.

But it was his My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story that told the tale of how a local hospital in a small town – Johnson City in Tennessee – treated its first Aids patient, that pitchforked him into the literary limelight. A specialist in infectious diseases, Dr Abraham was working in the hospital at the time and quickly became the local Aids expert after he began seeing first-hand what was happening in the conservative community where an overwhelming number of people ended up in his hospital as HIV-positive patients.

Their stories consumed his mind and his life. ‘That’s actually the moment I became a writer,’ says Abraham. ‘I had no intention of becoming a writer but living through that story in a small town in Tennessee….’

He initially wrote a scientific paper about the phenomenon of high numbers of HIV in a small town. ‘[But] that language of science didn’t quite capture the heartbreak of these young men and their families… and my own grief caring for them and watching them succumb. So… I decided to try and tell that story for the general public.’

Was it a catharsis of sorts? I ask.

‘I suppose,’ says the author, a faraway look coming over his eyes for a moment. ‘I had been writing short stories during that time as a sort of release [and was] not looking for publication; it was more for entertainment.

‘Also, in a short story and fiction, you can defy the elements that otherwise limit you, including death. Fiction is the great lie that tells the truth. So that’s how it all started, you know, writing.’

In an interview to Scope, of Stanford Medicine, Abraham underscores how ‘writing fiction was my escape.

‘In my stories, I could keep people alive, and I could reverse the course of disease. Writing has its great challenges, like keeping readers interested, but it’s a relief from the sometimes sobering reality of medicine.’

The loving grandmother, a teacher of physics, penned her answer in longhand even including illustrations – ‘she was an accomplished artist’– that detailed her family lore, friends, family characters, seasons and lots more.

The lovingly handwritten document was full of anecdotes and drawings, he remembers. ‘And while I never used those stories, it was a great reminder of the richness of the community [in Kerala] and [I thought] how interesting it would be to set a novel there.’

Although Abraham didn’t grow up in Kerala, he has fond memories of visiting his parents’ hometown during summer holidays’.

Born in Ethiopia to a school teacher couple from Kerala who were invited by Ethiopia’s then ruler Haile Selassie to work in the east African country as teachers, Abraham grew up there before his family moved to the US following civil unrest in the country.

‘I grew up there but I was also going home to Kerala every summer for two months at a time, so it’s not as though I was unfamiliar with it. I was very close to my grandparents, and later in medical school – Madras Medical College – I spent a lot of time with them.’

HOW HE TREATS PATIENTS

Dr Abraham is known to treat patients by relying heavily on a thorough visual and physical examination; this when online reports suggest that medical practitioners on average spend less than 15 minutes with patients per visit. ‘One of the great things about being educated in the second half of my medical training in India was to be trained in this classic British system of learning to read the body by careful examination and judicious use of tests,’ he says, explaining why he spends more time with patients to understand their condition. ‘So, if I’m examining patients carefully, I’m only doing what we’re all supposed to be doing.’ He makes it clear that he is not a Luddite. ‘I love technology. I just think there are dangers to becoming so reliant on it that you ignore your own senses you ignore the thing you were trained to do.

Those summer holidays clearly left him with lasting impressions and memories of the south Indian state, the richness of his community, and the breathtaking geography of the region.

For Abraham, that last factor is crucial to a novel. ‘I think the biggest decision in a novel is always geography; [if you have it], everything follows.’

Once the setting was confirmed, the winner of four literary awards including the 2023 Writer in the World Prize began his research making several trips to Kerala. Luckily for him, he had ‘wonderful cousins, academics and friends in Kerala’ who helped him a great deal in getting details including those related to history, politics, religion, and local and international issues that were high on the agenda at the time

He plotted a lot of this on a spreadsheet and the board ‘to make sure that at every moment I was aware of where the character was situated in the larger scheme of the world history’.

Did he expect the book to run to over 700 pages?

‘No,’ he says. ‘I don’t think a writer ever sets out to write a long book. But when you’re trying to encompass three generations and make the characters come alive, it becomes a long book.’

It also helped to have an understanding editor. ‘My editor [Grove Atlantic’s deputy publisher Peter Blackstock] was wonderful,’ says Abraham. ‘At one point he said ‘the story has to be as long as the story has to be.’

A good call; if anything, the length of the book offers readers a much deeper, more insightful and far more immersive experience.

If some of the characters in the Covenant of Water are in a sense orphans, ‘cut from the fabric of loss’ as Abraham writes, as many are also seeking a place they would like to call home, including some of the Westerners who arrive out of choice – or are born – in India but know that they may never be able to call the country their home.

Abraham himself was born on one continent, educated in another and is now working in a third. While he calls America his home and is proud to be its citizen, ‘I don’t feel like I truly have a hometown in the traditional sense’, he said – a reason perhaps he gave his characters a strong sense of home.

Even as the book explores the intricate story of three generations, parts of the book also offer a deep insight into medicine and medical procedures not to mention the joys, sorrows and, on many occasions, the physical and emotional turmoils doctors experience in the course of their professional life.

Being a doctor must have surely helped when penning these sections, I mention, before asking him what drew him to choosing a career in medicine.

‘It was very much by choice and that happened to align with what my parents were obviously happy with,’ says the doctor. ‘The example they set made us reach for our best when we could.’

Writing has its great challenges, like keeping readers interested, but it’s a relief from the sometimes sobering reality of medicineDr Abraham Verghese

He admits that he was an indifferent student. ‘But my moment of being called to medicine came from Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage and that’s actually true of a generation of physicians who could point to certain books like The Citadel. For me, it was something in Somerset, almost a casual line, because the book is not a lot about medicine.’

The line describes the orphan Philip Carey walking to a hospital ward to begin his clinical training: ‘Philip saw humanity there … and said to himself, ‘There is something I can do. This is something I can do well.’

Says Abraham: ‘This [line] made me feel that even someone like me, who didn’t really excel academically but who had a curiosity about the human condition, could, you know, with hard work, be a good doctor.’

The winner of the Humanities Medal from President Obama in 2016 does not believe that being a medical practitioner and a writer is about juggling two different worlds. That said, in many ways, doctors have a slight advantage when it comes to writing, he believes.

‘The same lens that I have used for many years as a physician – looking at patients with a great deal of curiosity and empathy – is the same lens that I bring to writing,’ he said.

TIPS FOR ASPIRING WRITERS

‘I think I’m being facetious when I say this, but the most important thing for someone who aspires to write is to have a good day job, one that they love. ‘There’s nothing harder for a writer than having to pay the bills based on their writing. That puts a kind of strange pressure on the writing; I’ve been very blessed to not feel that urgency, not feel that pressure.’ ‘God bless if you get to a point where you can give up your profession so that you can write full time. I probably could do that with some sacrifice, but the money comes so sporadically. But more importantly, I wouldn’t want to do that. I love medicine. I love teaching.’

What does he do when not writing, treating patients or teaching?

‘I walk,’ says Abraham. ‘I love to walk which is a nice way of listening to audiobooks.’ While he doesn’t watch a lot of TV or play golf, the Stanford professor practices Transcendental Meditation once or twice a day. ‘I’m not always successful,’ he says with a laughs, ‘but it’s a wonderful exercise; it opens the mind and brings a new perspective.

‘You can be the observer looking in and watching the emotion instead of being the emotion.’

For Abraham, emotions clearly mean a lot. ‘Every morning I begin my day with a thank you,’ he says. ‘Gratitude, because, you know, every day above ground and being mobile and in your senses is something you need to be grateful for.

‘So every night when I go to bed, I try to list five good things that happened that day. Even on the worst day, you can find five. For instance, the fact that you are breathing is a good thing. This list sort of makes the day special.’

Abraham is also a voracious reader and can’t stress enough on the joys of reading.

‘I remember sharing with Oprah one of my favourite quotes by Mark Twain: The difference between people who don’t read and who can’t read is no difference.’

But for those who may not be fans of books, there is good news: Oprah is planning to make a series of podcasts of The Covenant of Water – the first time she is doing something like this.

Later, after the interview I was scrolling through my Facebook feeds when I chanced upon another video in which Oprah was discussing the book. ‘I have been reading since I was three years old and over the years I have collected several books,’ she says. ‘But [The Covenant of Water] is going to be one of the top 3 books of all time and that includes Ms Toni Morrison. I have never felt this way about any book.’

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox