Life after ‘The Cement Garden’

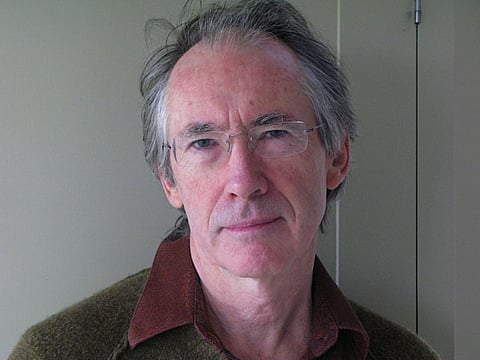

While a new production of his first novel is being staged in London, Ian McEwan responds to criticism that he has lost his bite

Ian McEwan was in Iowa in late 1977, teaching on a writers’ workshop, when he got a call out of the blue. An American editor was on the line. She was a fan of his short stories, she said. There were rumours he had just completed his first novel. Would he care to send it?

McEwan offers a short, dry laugh. “I said no. I can’t imagine what I was doing. And she said: ‘Well, what if I got on a aeroplane, stayed with a friend at the workshop, and he happened to leave your novel on the table?’ So I said: ‘OK.’” A slight pause. “Then she wanted to know what the title was. I had no idea. She said: ‘Why don’t you call it The Cement Garden?’ I just agreed.” He shakes his head. “It hadn’t even occurred to me, the business of a title ...”

The rest is, if not quite history, then at least publishing legend. Just 138 pages long and narrated in the deceptively affectless monotone of a 14-year-old boy called Jack, “The Cement Garden” tells the story of how he and his three siblings retreat into their own world after the death of their parents. The garden in question may have been concreted over by their father, but it is when their mother dies — and her body requires disposal — that the spare cement comes into its own. Freudians will be able to guess the rest.

The book became a cult hit on both sides of the Atlantic, and earned McEwan, as well as a new career as a novelist, an inevitable soubriquet: Ian McAbre. One American critic was wittier: McEwan’s fiction, he wrote, paraphrasing Hobbes, was “nasty, British and short”.

Four decades on, coiled into the corner of a sofa in the formidably tidy lounge of his house in Bloomsbury, London, McEwan could hardly seem less macabre. The sun streams in through the windows as he motions me to sit down. I try to put my finger on who he reminds me of: a studiously unflashy neurologist, perhaps, like the protagonist of his 2005 novel, “Saturday”.

The universe conjured up by “The Cement Garden” feels almost unimaginably distant, I say — not least for anyone acclimatised to the more genteel landscapes of McEwan’s recent fiction. Where did it come from? “It was the late Seventies,” he says. “Everyone seemed focused on a sense that we were always at the end of things, that it was all collapsing. London was filthy, semi-functional. The phones didn’t work properly, the tube was a nightmare, but no one complained. It fed into a rather apocalyptic sense of things.”

The book probes some dark places: there are heavy hints of child abuse, and the relationship between Jack and his older sister Julie proves far from innocent. He shrugs. “I don’t know about words like dark. I thought it was funny, too: having a secret like your mum encased in cement in the basement.” There is a flicker of a smile. “Maybe that was just me.”

“The Cement Garden” being staged by the young company Fallout Theatre, in a new adaptation that preserves all of the menace — and a good deal of the physical horror — of the original. The setting will be appropriately crepuscular, too: former railway tunnels beneath Waterloo station. It is not the first time the book has made its presence felt off the page: in 1993, it was made into a film by writer/director Andrew Birkin, starring Charlotte Gainsbourg as a dangerously playful Julie — the first of several screen versions that have made McEwan into one of the most adapted writers alive.

Does it feel odd, watching someone else imagine a world you have created? “It is strange,” he says. “Distancing. But you realise you’re just watching one of the infinite number of possibilities. Sometimes it’s really beguiling: when Joe Wright cast Saoirse Ronan as Bryony in ‘Atonement’, she completely invaded my sense of my own character. Now I can’t read the book without seeing her.”

Given his apparently serene progress as a novelist, it is almost heartening to hear that things have been significantly bumpier on screen. After tasting success with “The Ploughman’s Lunch”, a Channel 4 film set during the Falklands conflict and directed by Richard Eyre, he had ambitions to alternate between novels and screenplays. “I thought: ‘Oh, this is how life is going to be. I’m going to write a novel, pause and write a movie, and then go back to another novel.’” He looks rueful. “Of course, it’s never happened so easily since.”

“The Child in Time”, about a couple recovering from the abduction of their 3-year-old daughter, has been in development ever since it was published in 1987. McEwan’s own screenplay of “On Chesil Beach”, intended for the pre-Bond Sam Mendes, is languishing without a director. And we haven’t even got on to the tale of his legal battles with Hollywood over a film he wrote for Macaulay Culkin — still less the long-cherished but abortive plans to write a sequel to David Cronenberg’s “The Fly”. “I thought it was the perfect movie for me. But Geena Davis fell out with the studio about something, and because she only owns half of the ‘fly concept’” — he delivers the words with heavily curlicued irony — “we couldn’t even go into turnaround.”

McEwan also once had ambitions in the theatre. His friendships with Eyre and Harold Pinter (the latter adapted “The Comfort of Strangers”)are well known, but I have read that he once wrote a play of his own. What became of it? He winces. “Oh, no, I was an undergraduate and I’d started writing all kinds of things. It had a character who told everyone else they were in a play.” He covers his eyes. “Truly terrible.” So would he be tempted again? “Well, every now and then I think I will write a play. I’d love to write Richard something. But I haven’t quite got the ...” The sentence lingers unfinished.

McEwan cracked a rib recently on a trip to Bavaria, indulging his longstanding love of hiking. That aside, he seems in energetic form and, twenty-odd books in, is as quietly productive as ever. The first draft of a new novel is nearing completion: a legal procedural based on the real-life story of a teenage Jehovah’s Witness who refused a blood transfusion, continuing his longstanding fascination with the boundaries between science and ethics.

Although “On Chesil Beach” was acclaimed for its McEwanesque combination of forensic elegance and creeping disquiet, reviews of his most recent books, “Solar” and “Sweet Tooth”, have been more muted; some have wondered if his writing still has the same bite or vehemence. Novelist John Banville used the dread word “mellowness” in a review of “Saturday”. Does he accept the criticism? He stiffens. “If you’re comparing them to what I was doing when I wrote ‘The Cement Garden’, then yes. But you can’t in your mid-60s write as if you’re 25, or want to. There’d be something weird about you if you did.”

Would he ever leave it all behind? “Writers are a bit like politicians — they never quit while they’re ahead, they have to fail and then quit. But I doubt it. Not unless I go completely nuts.” There is a touch of defiance in his tone. “I’ll be retired — it won’t be an active choice. Anyway, I’m in the toddlerhood of old age.”

An avid fan of chamber music, McEwan talks enthusiastically about his collaborations with the composer Michael Berkeley, which began more than 30 years ago with the oratorio “Or Shall We Die?”, and produced most recently the opera “For You”. “I think I’ve got an urge to be more collaborative,” he reflects. “The long solitude of writing a novel, talking about it, then starting all over again in the foothills of yet another, needs to be broken somehow. When musicians assemble, when you’re caught up with other people’s professionalism — that can be wonderful.”

But he can’t imagine life without writing, he says. “There’s a lovely phrase V.S. Pritchett used: ‘determined stupor.’ I don’t know what I’d replace that determined stupor by. What else is there?”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

“The Cement Garden” is at Waterloo Vaults, London SE1, until March 8.