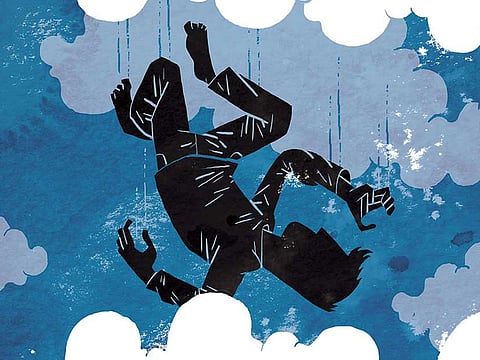

Falling through time

Three men, separated by three centuries, witness an Australian miracle

The Body In the Clouds

The Australian writer Ashley Hay’s second novel, The Railwayman’s Wife, was a contender for her country’s premier literary prize, the Miles Franklin award. Which may explain why her exquisite first novel, The Body in the Clouds, is finally being published in the United States. At its centre are three men, seen in three different eras of the history of Sydney, whose lives are joined and changed by witnessing the same miracle: a man falling from the clouds into the sparkling harbour yet surviving, “marvelously alive”.

Dawes is an 18th-century astronomer, fresh off the first ships to settle Sydney, when he hears something “almost thunderous” hit the water. In 1930, Ted is a teenager, marvelling at the partly constructed Sydney Harbour Bridge, when he sees the event he’s dreamed: “Everything fluttered down to silence, Ted felt the dog’s hackles stiffen under his hand, felt his own frame freeze to tautness. Someone was falling; someone was falling off the bridge.” Dan is an Australian banker living a half-life in contemporary London when, in a nightmare, he imagines himself “falling suddenly, falling down through the air towards the water, a man’s voice yelling from below, ‘Get yourself straight, get yourself straight, lad’.”

What if, Hay wonders, “something singular, unexpected, happened in some particularly malleable place, maybe it couldn’t help but leave a trace — or alert you to its coming.” This magic realist device forms the core of a rich, meditative novel that explores the connectivity of people living in the same geographical space across the distance of time. Through a series of satisfying, recurrent metaphors — repetitions of images, phrases, objects and dreams — Hay weaves her characters’ stories closer, offering an allegory for the commonality of human experience. Her deft touch means that these connections are never forced; rather, they give the book the feel of memory, of a half-waking dream.

Foremost in these metaphors for interconnectivity is the bridge itself: a sketched possibility for Dawes, an exhilarating construction job for Ted and a beautiful structure dominating Sydney’s skyline and Dan’s homesick dreams. The bridge is, in essence, a major character — as it is for any “Sydneysider” — and Hay celebrates the city’s grand connective tissue, the sense of continuity through history the bridge represents.

Crucially, it prompts Hay’s meditations on narrative perspective, on witnessing time and space in different ways. Dramatised in the man’s fall through the centuries — and more broadly through her characters’ shared interest in comets, flight and stars — the conceit of viewing from above is used to represent the authorial omniscience that lets her look down through time and find the uniting essence of a place. That artistic intention is spoken aloud towards the end of the novel: “I was trying to work out how we must really look, smeared across time and space ... What traces we must leave”; “You’re looking for overlaps, coincidences, aren’t you, love? Bits of time between now and then that are the same? ... Just keep going down through the layers and you’ll find intersections.”

Hay finds those intersections in her engagement with intricate metaphors, aligned so neatly through three narratives that they combine to give the novel shape and structure, to generate resonant climaxes as each character finds a sense of connection, self and home in the patch of land around the bridge. These grander literary concepts are conveyed in Hay’s elegant prose, which draws warm and textured portraits as it celebrates the web of human stories woven around this harbour — from the first aboriginal inhabitants through the early British settlers and on into the tumult of modern urban life. Within that sprawl, Hay discovers beauty.

–New York Times News Service