As long as it’s good

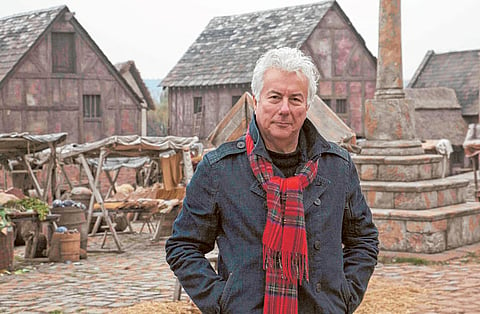

Ken Follett shares his thoughts on “Winter of the World”, and the ideal length of a novel

Retaining reader interest right through a sequel that is more than 800 pages long and weighs a tonne is no small feat. But Ken Follett manages to do just that with “Winter of the World”, the second instalment in his Century Trilogy, which was released worldwide on Tuesday. In fact, he does it with such dexterity that there’s barely a need to consult the long “Cast of Characters” list at the beginning of the novel.

“Winter of the World” picks up where “Fall of Giants”, the first book, ended. Follett takes us through the rise of the Third Reich and the global tumult it sparked, all the way through the Spanish Civil War, the devastation wrought by the Second World War and the atomic explosions that created the New World Order. Through the eyes of his memorable characters, we get a ringside view of some of the most important events in modern history, from 1933 to 1949.

“Winter of the World” is the intertwining tale of five families — English, Welsh, American, German and Russian — and their hopes, fears, desires and ambitions. All in the backdrop of the worst conflict in human history. Most of the characters are those from his first book, with additions as families expand. The von Ulrichs’ daughter, Carla, is a sensitive soul who is vehemently opposed to the Nazis while her brother Erik joins the German armed forces. Gus Dewar’s sons, Woody and Chuck, find themselves serving the United States in the Pacific. Gregori Peshkov’s son Volodya is a Stalin loyalist while his American cousin Daisy Peshkov is desperate to climb the Washington social ladder. The idealistic Englishman Lloyd Williams discovers the evils of Communism while fighting on the side of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

As with the first book, the historical research is impeccable. The chapters that deal with the social context in the lead up to the Nazi takeover in Germany; the ups and downs of the Spanish Civil War; and the behaviour of Allied — especially Soviet — soldiers in Germany towards the end of the Second World War are particularly interesting for any history buff. In a telephone interview, I asked Follett if it was important for him to inform and educate readers, as opposed to just entertaining them. “Yes, I think it is part of what we want from novels. We enjoy the drama and the escape to a fictional world, but when we put the book down we’d like to think we have learnt something. I don’t write my books primarily to educate people. What I am focusing on is writing something they will enjoy and lose themselves in. Nevertheless, I like my readers to think that they are learning something from the book. That is why I go to a great deal of trouble to make sure that history is accurate.”

He added, “A lot of readers don’t like the sense that the author doesn’t really know what he is talking about. Whatever the background, history or science, readers like to feel that the author has taken the trouble to get all that right.”

The story does not end with the Second World War. Follett said: “I felt to end the book with the end of the war gives a false suggestion that all problems are now solved. So it was important to show that war does not solve all problems; it creates some new problems. And to at least give an indication of some of the dramas that were going to follow, I continue the ‘Winter of the World’. For instance, the development of the Soviet nuclear bomb. I wanted to show some of the new issues that were coming up and will be dealt with in full in the third book.”

A strong aspect of “Winter of the World” is that you really don’t need to have read the first book to understand the second one. Follett described how he goes about planning his novels: “The first step is to do a lot of reading, such as historical reading. And to identify the historical events which are the most important in that period. The second step is to invent the cast of characters who could be involved in those events, and then I need a lot of detail. For example, if I was reading about people escaping over the Berlin Wall, from East to West Berlin during the Communist era to write about scenes in which people escape, I will need very precise details about the Wall and the ways they found to get over it, or under it or around it. That kind of detail is very important. “

There are strong female characters in his book; Follett shows women struggling and making a role for themselves despite their oppression in society. “I hope we see that anyway. I think that is part of what happened in the 20th century, isn’t it? Women were more and more successful against male hegemony.”

As with his first book, and given the complexity of the plot, Follett for the most part does an admirable job of arranging for the paths of his international characters to cross in plausible ways. But I am not a fan of coincidences, and at times you feel the author is pushing it a bit in the book.

Throughout “Winter of the World”, just like in “Fall of Giants”, Follett has made an effort to give the other side of the story, to explain, for instance, the rationale behind the Japanese attacking Pearl Harbor and launching a war against America. He also addresses the issue of England’s bombing campaign against German civilians. In short, not much of black and white, good and evil. “I am glad you felt that way. I certainly wanted to give a broad view and understand the point of view of the many different nations, not just the British. When you write about these things you have to see them in the round, you even have to think why the Nazis were successful. Nobody thinks they were good, everyone thinks they were evil. But you have to see why they were successful and why some people voted for them. So I think it is part of my job as a novelist to try and see all sides of things.”

What is it with trilogies that makes them such long reads? Asked if he thought a trilogy or any book that is part of a series has to be very long, Follett said, “I don’t think it has to be long. The only justification for a long book is if people are enjoying it. So if people are enjoying it they want to go on longer. My hope certainly is that when people finish ‘Winter of the World’, they hope it should have been longer. There is no right length for a novel. It should go on for as long as the story is good.”