A gripping tale of escape from the USSR

Ben Macintyre tells the story of MI6 agent Oleg Gordievsky’s rescue from Moscow in 1985 with elegance and wit

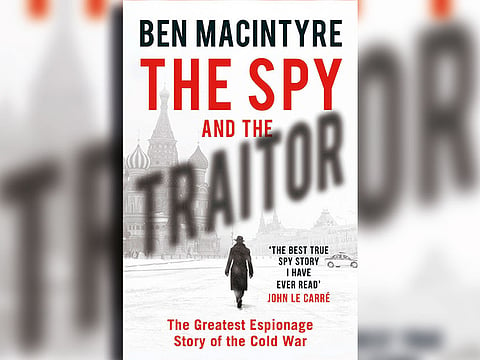

The Spy and the Traitor: The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War

By Ben Macintyre, Penguin, 384 pages, £20

Oleg Gordievsky is not a household name, but he should be. Not only did he make a significant contribution to the ending of the Cold War, he did so as Britain’s most important foreign agent. A KGB colonel working for MI6, he exposed Soviet plans in Scandinavia, Britain and elsewhere and — most valuably — alerted leaders of the western alliance to Kremlin paranoia in the 1980s.

Without his insights, Cold War rivalry could have tipped over into Armageddon, so it’s not too far-fetched to say that we all owe him our lives, whichever side of the old iron curtain we live on. He’s deeply implicated in the warming of ties between the west and Moscow as well.

In a bizarre and perhaps unique piece of espionage, he essentially wrote the briefing notes for both Margaret Thatcher and Mikhail Gorbachev at their first meeting and thus can take much of the credit for the cordial relations that sprang up between them. His story has been told before, not least by himself in the autobiography he wrote in retirement in Britain, but it has found its ideal chronicler in this exceptionally rewarding book by Ben Macintyre.

Over the past decade, from his breakout success with Agent Zigzag to his biography of Kim Philby, A Spy Among Friends, Macintyre has built an entirely justified reputation for his true spy thrillers. Those books were good, but this one’s better.

In fact, it feels a little like he has been waiting all the time to tell us about Gordievsky, since this story is so much bigger than those he has told before. Gordievsky was KGB through and through. Born in 1938, just as the great terror was winding down, his father was a secret policeman and his older brother became one too. Bright and studious, he won a place at the prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations — the “Soviet Harvard” — and it was almost inevitable that he would end up in the Soviet Union’s most elite corps: the first chief directorate, the KGB division responsible for spying on foreigners, rather than harassing Jews, Baptists and free thinkers at home.

It is tempting to see him as a sort of mirror image of Philby, but there is one crucial difference. Whereas Philby was ideologically committed to communism before he joined MI6, and infiltrated the spy agency so as to betray it, Gordievsky became enamoured of the west when he was already on the inside.

Partly, he was appalled by the Berlin Wall, but mainly he was radicalised by the crushing of the democratic uprising in Czechoslovakia in 1968. Gordievsky was on his first foreign posting at the time — in Stockholm, where he was so bewildered by the freedom of everyday life that he bought homosexual pornography just because he could — and he felt he could no longer support the Soviet government.

A complex mating dance ensued, until he signed up to work for MI6, with one of his conditions being that he would not take payment. From the first, he was an exceptional agent who helped to expose spies working for the KGB, as well as to help MI6 understand its rivals’ methods. It simply hadn’t occurred to western politicians that their Soviet counterparts thought they were planning a nuclear attack but, thanks to Gordievsky, they were able to dial down their rhetoric in order to calm fears in the Kremlin.

“The pantheon of world-changing spies is small and select and Oleg Gordievsky is in it,” writes Macintyre. He was exposed thanks to another spy — Aldrich Ames, a CIA analyst who betrayed his country for money — and summoned back to Moscow. That sets up the book’s final third, which describes his interrogation by his colleagues and MI6’s improbably complex plan to rescue him, codenamed Operation Pimlico. The plan was almost derailed at the last minute: permission could not be obtained from Margaret Thatcher at Balmoral because the security guard was trying to sort out the Queen Mother’s video machine.

Fortunately, the video episode ended well, as did the escape. In July 1985, he was smuggled across the USSR’s border into Finland, the Soviet sniffer dogs distracted by a baby’s full nappy and a packet of cheese and onion crisps.

Macintyre’s prose is elegant and enlivened with occasional asides that are eminently quotable, as well as inevitable nods to the classics of the spy genre, above all John le Carré (one spy is “Our Man in Copenhagen”), but there is a key difference between the old master and Macintyre. Le Carré’s Cold War novels are full of an amoral bleakness; both sides are so worn down by the Cold War that there is little if any difference between them. The Spy and the Traitor, however, is in no doubt that Gordievsky was serving a cause that was just and correct with “an adamantine, unshakable conviction that what he was doing was unequivocally right”.

His decision to hand the KGB’s secrets over to Britain was a “righteous betrayal”. Moscow did not see things that way of course and Gordievsky, who is living somewhere in the suburbs, remains under sentence of death. The attempted murder of Sergei Skripal, another Russian who spied for Britain, in Salisbury earlier this year, gives this book an unexpected contemporary relevance. We are back in an age of tensions between the west and the Kremlin and we need people such as Gordievsky just as much as ever.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd