The memorable sight of a distraught figure, eyes tightly closed, grimacing and slapping his forehead in anguish as he stares at his feedback and TV box is the only-too-frequent giveaway that a troubled Formula One team boss is about to count the mountainous cost of a crash of one of his cars.

The dazzling Formula One showcase, a treasure of bravery and dash and daring of drivers ravenously hungry for success in pedigree and priceless transport, has suddenly, in the revealing light of the image of the tormented boss on the pit wall, sunk to dark and dismal depths with a damaging hit on the victim team’s bank balance.

If, like the team hierarchy, you cast your eyes over the wreckage of the car being crane-hoisted from the barrier zone it has just smashed into over 100mph, you could be looking at a repair bill amounting to millions of dollars.

The driver, superbly and safely protected, may climb out of his disaster area without a scratch or the faintest blemish on his ability. Or it could have been his fault after a split second lack of concentration. Whatever, the consequent follow-up will be a torrential repair bill.

In F1 the cashflow washes like a financial flood over the already wealthy top teams, the champions, the winners, while at the back end of the grid the lesser likes are stranded high and dry and struggling. Angry, too, that they do not receive a fair enough share of the funding from the Grand Prix organisers.

The current dole out is all set to occupy the deeper consideration of the money men behind the F1 scenes as the also-rans pile on the pressure for bigger handouts to stave off the grave likelihood of a disappearance from the scene, as has happened to several teams over the last decade.

New owners Liberty Media forks out to the grid occupants around 66 per cent of its annual profits reckoned, last year, to be around $985 million (Dh3.6 billion).

I’m told the front-runners in the cash dash are Ferrari who receive $180 million a year. They are followed by consistent champions Mercedes with $171 million, Red Bull on $161 million and McLaren, once a team of legend but struggling flops for the past two years, on $97 million. Compare those mind-boggling figures with the payout to humble back of the grid Haas, relative newcomers on the Grand Prix scene, with a miserly $19 million.

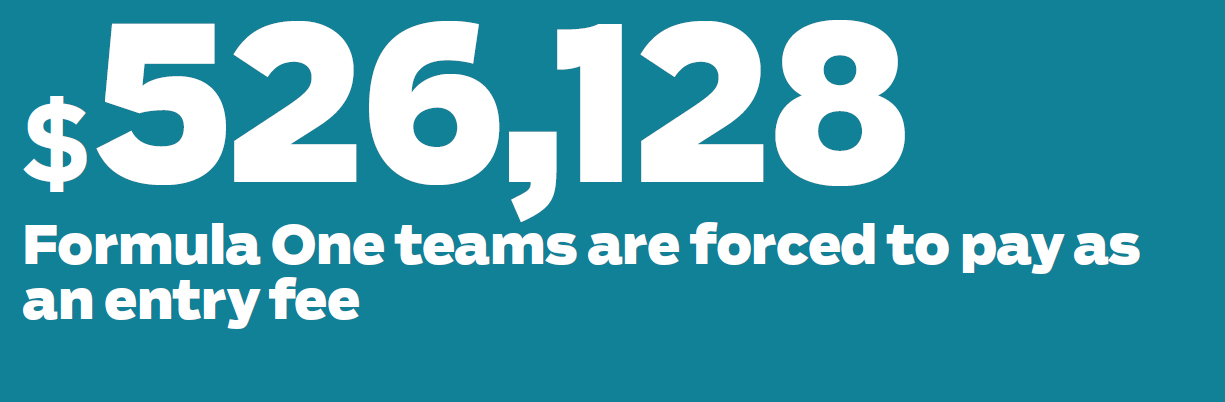

The money flows into F1 from hosting fees, worldwide film, media and TV rights and immense hospitality and trackside sponsorship arrangements with, its estimated for 2017, a turnover topping $1.83 billion with an underlying reserve of $1.38 billion. All teams are forced to pay an entry fee of $526.128.

Payments are made to the competing teams through nine monthly issues from April onwards — and they are judged on current performances, past successes and, as with Ferrari, special agreements that are traditional and top secret.

Now, back to that anguished team mastermind and the cornered signee of the repair bills to his damaged pride and joy. Here is a breakdown — as it were — of his imminent outlay for the smash up, often miraculously, all fixed in place as good as new overnight by his hard-working and tireless team behind the scenes.

An engine costs $8 million. The carbon fibre monocoque is $675.000 per chassis. A front wing and nose cone $170,000. Rear wing and overtaking aid $82,000. Fuel tank, plus assembly,$110,000. Hydraulics are $165,000, gearbox $490,000 and cooling system $160,000.

Oh, yes, and a steering wheel, the vitally essential highest-tech control handpiece with its complex array of buttons, readouts and dials, is pricier than the average family saloon at more than $50,000.

Little wonder if his car is a write off the team boss is in despair. He could be staring wondrously at a total cost of $950m.