Rapper Rapsody lends voice to the voiceless

Looking beyond her two Grammy nominations, and collaborations with Kendrick Lamar, she’s batting for rap’s female resurgence

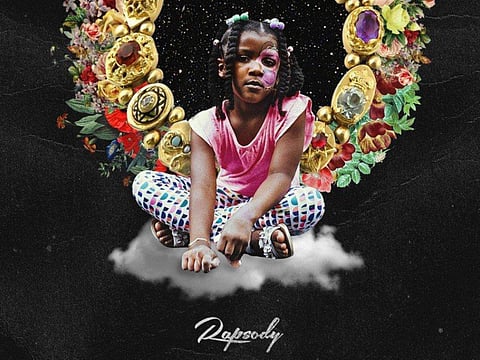

In January, 35-year-old Rapsody became the fifth woman ever to be nominated for best rap album at the Grammys, for Laila’s Wisdom — and picked up a nomination for best rap song, too. The self-described “tomboy” offers a ferocious voice to the voiceless: loaded with intricate rhyme patterns, wordplay and metaphors, her music coolly captures the essence of black women with a Maya Angelou-like grace.

At her fiercest, she damningly critiques the US’s complex prison system — “I know prison business, but nobody know how many innocent in it,” she raps on Nobody — and attacks negative perceptions of the darker skinned. “Black and ugly as ever and still nobody fine as me / No one been as kind as me,” she sings on Black & Ugly.

These are vulnerable, complex stories not being told by the likes of Nicki Minaj and Cardi B — who are all braggadocio and self-empowerment — and so Rapsody sits in parallel to rap’s female resurgence.

“I want to make music that people can feel and connect with,” she says in a soothing low register before her sell-out show at the Jazz Cafe, London. “I love making music that I care about, and if you listen to it, you can tell I care about my craft and people and our communities.”

Growing up in Snow Hill, North Carolina, Rapsody watched pioneers MC Lyte and Queen Latifah exert their influence on TV, and became immersed in the art of rapping to perfectly execute untold stories. “I just loved [rap’s] freedom of expression,” she says. “Whether that was the fashion, how you dance, how you walk — everyone had their own styles, and we could coexist. That was the beauty of hip-hop for me.” Initially, she says it was “just a dream. I didn’t have enough confidence to pursue [rapping]. It took me going to college and having my friends push me for me to take it seriously.”

In the early 2010s, Rapsody began her ascension, wielding lyrically dense odes to self-advancement and the sprawl of the black American experience. Mainstream rap was still a landscape in which lyrical skill was secondary, for men and women. Conscious, creative rappers such as Lupe Fiasco faced battles with their record labels, and underground veterans such as Jean Grae remained exactly that: underground.

Rapsody had her own jarring experiences. “Women weren’t looked at as being talented or able to compete with the men,” she says. “We were always reduced to fighting among each other; to some people, we had to prove we could rap, and, to others we had to look the part. But for what? What’s the point? Men can coexist, and women can do the same thing. But it feels good to know that I made it this far and didn’t have to compromise or change my style, how I looked, how I rapped and what I rapped about. My journey shows women do have something to say, and you can’t box us in and try to define us any more.”

Rapsody also earned the respect of rap’s elite — Kendrick Lamar included her on his epochal To Pimp a Butterfly album, where she delivered a magnificent perspective on the notion of black beauty for Complexion (A Zulu Love).

Mainstream recognition was fully realised on Laila’s Wisdom, featuring Lamar, Anderson .Paak and jazz virtuoso Terrace Martin, among others.

“That was the album where I said: [expletive], I’m not worried about proving to anyone that I can rap or that I’m not worthy enough,” she says. “I’m not going to waste time trying to fight for the same three million people [as] everybody else” — the established fanbase of rap — “I’m focusing on my lane and letting it build. I wanted to tell my story, something that spoke for black women, and not be afraid to tell the honest or ugly parts.”

In the Migos and Future-led era of money, drugs and excess, Rapsody has found a meaningful pocket within the culture.

Although no Grammy was forthcoming, she remains determined to stand for those voices who are seldom heard. “I remind myself that making good music and being myself got me here,” she says. “My purpose has always been to inspire and touch people, and you can’t hold that to an award — it’s so much bigger than that.”