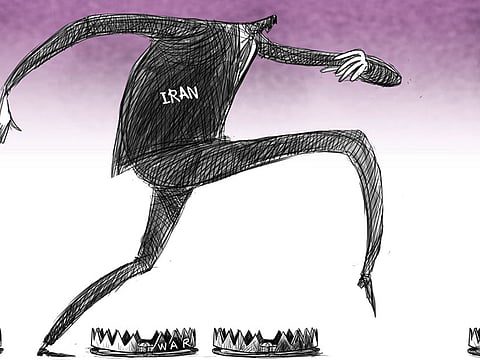

Iran eliminates possibility of war with the US

Tehran moves to avoid creating conditions that could trigger a conflict, but hints at other equally important concerns

Many analysts, including this author, continue to view a military confrontation between the United States and Iran under President Donald Trump as a real possibility. However, recent statements of Iran’s leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and some policies adopted at the highest level within Iran, indicate that Tehran has decided to avoid creating conditions that could trigger a war between the two states.

Central to the argument of those who warned about the possibility of a US-Iran war was that the US would likely re-impose crippling sanctions on Iran. This prediction was based on the uninterrupted expansion of Iran’s ballistic missile programme. In retaliation, the story goes, Iran would accelerate its ballistic missile programme. Eventually, the Americans’ patience would wane and war would become inevitable.

On October 18, reacting to Trump’s announcement of his confrontational strategy toward Iran, Ayatollah Khamenei said, and “A military confrontation will not occur (between Iran and the US). However, some problems could happen that are no less important than war. We have to be careful.”

Following Khamenei’s remarks, a critical question arises: Why did Khamenei say with such certainty that war will not happen, and what are the other problems that he referred to?

Some may assert that Khamenei’s view regarding the unlikelihood of a US-Iran war is an overestimation of Iran’s military capabilities. To them, he is convinced that the US would not enter into a war with Iran due to its high cost. Iran’s military commanders have presented such an argument. However, a recent and unexpected position Iran adopted may convince outside observers that Iran’s strategy is to distance itself from acts that may provoke a war.

On October 31, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) commander, Mohammad Ali Jafari, announced that, according to a decision made by Iran’s leader, the range of Iran’s missiles will be limited to what it is now, 2,000km. Jafari added that “there exists the capability of increasing the range. For now, this is enough.”

A senior member of the Iranian parliament’s National Security Commission, Heshmatollah Falahat-Pisheh, said on November 6 that the missile-range decision was made in 2011. However, a lengthy report published in 2013 by the semi-official Mehr News Agency, which has ties to the conservatives, contradicts Falahat-Pisheh’s remarks. That report, titled “All Iran’s missiles: from supersonics to intercontinental,” clearly demonstrated that some Iran’s ballistic missiles had a range greater than 2,000km. One such missile, named Ashura, has a range of 2,500km and is highlighted as “the crown of Iran’s missile industry.”

It is clear that Iran, by announcing its decision to limit the range of its missiles to 2,000km, has decided to put to rest one of the most contentious points with the US.

By adopting this policy, Iran seeks to achieve another goal. Because the European Union (EU) has also consistently objected to the expansion of Iran’s missile programme, an unstoppable programme could both unite Europe with the US in adopting an aggressive stance and collectively bring back sanctions that existed prior to the nuclear agreement. Iran’s policy, then, could divide the EU from the US on a quarrelsome point.

In his recent statements, Falahat-Pisheh has discussed the two goals that have been targeted by the announcement of limiting the range of the missiles. He stated, “Limiting the area of conflict with the enemy (the US) must be included in our agenda. … [Meanwhile], by limiting the area of conflict with the US, we can make the Europeans believe that Iran’s cooperative approach is not solely focused on economic areas. They can also expect military cooperation from Iran.”

But what are Khamenei’s other concerns that are no less important than war?

Two concerns are revealed by reading between the lines. The 2009 upheavals following the disputed presidential elections, which led to the victory of Iran’s eccentric president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, rang alarm bells for Iran’s deep state. After eight years, the movement – labelled “sedition” by the conservatives – and its leaders, are constantly under heavy attack by the enormous state-owned radio and TV networks and other conservative media (no private TV or radio network exists in Iran). This is clear evidence that the deep state still lives under the shadow of fear of the re-emergence of that massive uprising.

The IRGC commander, Mohammad Ali Jafari, once remarked, “The 2009 sedition was a bigger threat to the Islamic Revolution than the imposed war [by Iraq].” To understand the significance of this comparison, consider that the eight year Iraq-Iran war (1980-1988) was one of the bloodiest and longest wars of the 20th century. Moreover, it began by a surprise Iraqi invasion following Iran’s revolution while the management of Iran was still in chaos, and Iran’s regular army was in a state of disarray.

On another occasion, Jafari has said that Iran’s leader “is concerned about internal problems and internal opposition” within the Islamic Republic. He maintained that foreign threats provided Iran with an opportunity. “External enemies such as the US and the Baath Party of Iraq, which attacked Iran as a US proxy, were not a threat against the Islamic Revolution. Rather, that was a golden opportunity for the export of the revolution to the whole world”.

The issue is of greater concern when considering the US Secretary of State’s comments in June before the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Before that committee, he said that US policy toward Iran is driven by relying on “elements inside of Iran” to bring about “peaceful transition of that government.” He added, “Those elements are there, certainly as we know.”

The other issue that Khamenei is deeply concerned about is the “infiltration” of the enemy and its creeping influence in the post-nuclear-deal era. This vision, which is shared by the conservative deep state, correctly believes that Americans and the moderate current within Iran tend to put the hostilities aside to restore relations between the two states. In such an eventuality, the radical current will be pushed to the margins. Iran’s centrist president, Hassan Rouhani, has repeatedly made clear his willingness to negotiate with the Americans and move in the direction of détente with the US.

Ayatollah Khamenei has said, “Who is prone to be influenced [by the enemy]? Primarily our elite, those who are effective [in the country’s direction], and decision-makers. They are prone to be influenced. These are the people that [the enemy] tries to influence.”

It was for this reason that soon after the conclusion of negotiations on the nuclear deal between Iran and the world powers, a major part of which was bilateral talks between Iran and the US, Khamenei banned any further talks with the US on any other issue of conflict between the two countries.

“We are in a critical situation now, as the enemies are trying to change the mentality of our officials and our people. … Through negotiations Americans seek to influence Iran ... but there are naive people in Iran who don’t understand this,” he remarked.

Shahir ShahidSaless is a political analyst and freelance journalist writing primarily about Iranian domestic and foreign affairs. He is also the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox