He mixes with the great and the glorified, but grace and graciousness remain a part of Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s persona.

When young, he might have nursed a grudge over not living a normal childhood, but the sarod maestro feels more than compensated for the love and adulation he has received from people of different nationalities all over the world.

At 66, Khan keeps a busy schedule. His concerts take him in and out of the country the year round. Amidst it all, the much-celebrated person takes out time for an exclusive chat with Gulf News.

Talking of his childhood, Khan says: “We shifted to Delhi from Gwalior in 1957-58, after a cultural organisation appointed my father Ustad Haafiz Ali Khan, also a sarod player, as a guest resident. We lived in different locales in Delhi, even as I studied at Modern School in Barakhamba Road. We finally managed to purchase the present premises.”

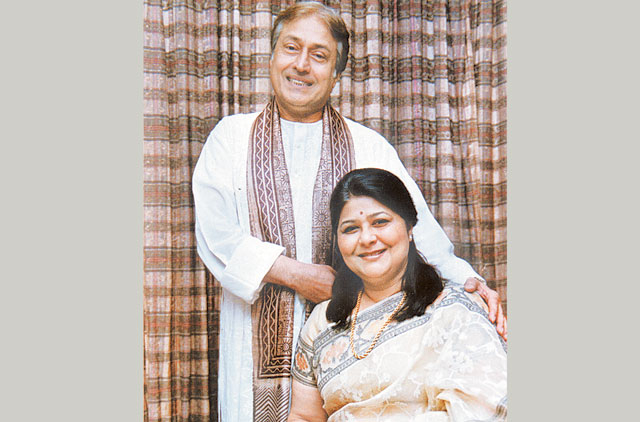

The bungalow in Sadhna Enclave, adjacent to Panchsheel Park is an extension of the personality of the inmates of the house. The tastefully done interiors are the brainwork of Khan’s beautiful wife Subhalakshmi, a bharatnatyam dancer. And the peace that the place exudes and the tranquillity of the ocean one feels, undoubtedly, is sealed in the charm of the couple’s accomplished sarod-playing sons Amaan and Ayaan. Intermixed with all this is Ayaan’s wife Neema’s contemporary taste, which works to embrace the whole ambience.

The classic sensibilities of the Khans greet you with a strange kind of positivity. The family has been residing here for more than two decades. And while the façade looks as charming as the master of the house, the interiors strike a fine balance between photographs and paintings that speak volumes about the family.

As if reading my mind, Khan says: “I do not unnecessarily interfere with what looks good in the house and where a particular piece of furniture should be kept.”

That put to rest my mind wondering how a place can look so peaceful.

With an extended driveway space for the swanky vehicles, the house overlooks a small lush garden. The basement includes a library-cum-sitting room and opposite it is the epicentre of the house — the music room.

With plain walls and wooden flooring, the room has nothing that could distract the musicians from pursuing their passion. This is where Khan and his sons compose music. “I also use it for meditation,” Khan quips.

The three floors are connected via an elevator inside the house. While the first floor includes the dining and living areas, the second floor houses Amaan and Ayaan, and the third floor is the abode of Khan and Subhalakshmi.

New things

As I get set for the informal conversation with the legendary maestro, he looks at me naively, probably wondering what new things he could say after having given unaccountable interviews.

Seeing his innocent look, I ask him if that was the reason why he was named Masoom (meaning ‘innocent’ in Hindi) Ali Khan as a child?

Giving his trademark smile, Khan says: “I do not know that. But I was renamed after a saint who frequented our house to listen to my father’s music, and suggested that the name be changed to Amjad.” Thus began another glorious chapter in the history of Indian classical music.

But later, the name Amjad resulted in creating some light-hearted moments in Khan’s life. In a case of mistaken identity, a young enthusiast ended up meeting the musician instead of Bollywood actor Amjad Khan of Sholay fame.

“We were forever exchanging a pile of fan mail that showed up at the wrong address due to similarity in our names,” Khan informed.

Talking about actors, Khan was reminiscent of how his love for musical instruments, including sarod, got Amitabh Bachchan and him to play the dholak together, as the superstar also sang one of his popular songs Mere Angne Mein Tumhara Kya Kaam Hai from the movie Laawaris.

Given the fact that Khan has always been strikingly handsome, did he never consider becoming an actor or compose music for films?

Khan said: “There was never any such temptation. I am probably one of the few musicians who did not shift base to Mumbai. While I maintained good relations with film stars, I found that the climate of Mumbai was not conducive to my instrument. Sarod is meant for a moderate climate and the humidity level of Mumbai goes against it.

“Also, to carry the legacy and becoming a successor is a very responsible job. In the process, one has to make many sacrifices. And, fortunately, unlike many film artistes of the yore, who came from a humble background and joined the film industry to earn money, I was not all that needy. My aim was to do my family proud by excelling in what I had been handed over.”

Khan though could feel content, as documentaries have been made on him testify.

Canadian director James Beveridge made one in 1971, followed by about half-a-dozen later, including lyricist Gulzar’s in 1990 for Films Division.

“A French director was also very keen to document my life. I had given my consent and he had been sanctioned a huge amount. But later he put a ludicrous condition. He wanted me to sport long hair, grow a beard and look like a baba or a guru. This was quite ridiculous and he was very disappointed when I refused,” the musician said.

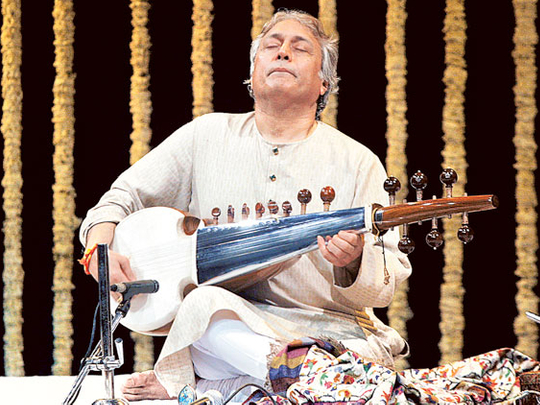

Khan’s great grandfather Ustad Ghulam Bandegi Khan came from Afghanistan.The family descended from the Bangash clan and migrated to India centuries ago with a talent for the rabab. His grandfather Ustad Ghulam Ali Khan carried on the tradition and modified the rabab, perfecting the instrument and polishing the practice of playing ragas. It was then named sarod, meaning ‘melody’ in Persian.

Khan’s father inherited the rich culture and became a court musician in Gwalior. He taught his son from the age of six years. “Tragically, by then he was already very old. He died in 1972 at the age of 95,” Khan laments.

The father-son duo had a unique way of teaching and learning. The father, like most musicians, sang to express himself and he taught sarod to his son even while he sang. But Khan did not incorporate singing while playing. “I let my sarod do the singing. Even today, I treat every concert as a challenge. Treating each one as my first recital, I make sure that the performances differ in every state. For, music should not sound identical,” he says.

While Haafiz played for the royalty, his son has taken it to the masses, willingly and eagerly sharing it with the audience globally.

He says, “I learnt an important lesson from my father. He once said, ‘Music is like the ocean. This gift of God does not belong to any race or culture. And to be a complete musician, one needs to learn the traditions of others and pick the best of all that is there’.”

Khan represents the sixth generation in this great tradition. He has affixed a new dimension by involving his sons, who are also accomplished sarod players in their own rights. The two are the seventh generation, with a new endeavour — to promote classical music among the youth.

Having given so much to the world and the younger generation, I ask him, what is that one thing he has learnt from the new generation? Khan says promptly “I have taken inspiration from my sons, who wrote a book on me. I am also writing a book and shall dedicate it to my father.”

Tradition

The sarod maestro is happy that the young generation is taking up sarod, sitar and tabla and sees no need to fear about the future of Indian classical music. Recently, he tried to bring his own tradition into the orchestral sphere in his sarod concerto written for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in Edinburgh, UK.

Ustad suddenly sings one raga formula, which tempts me to request him to sing a monsoon raga considering the warm and sultry weather these days, with no rains in sight!

He has experimented with modifications to his instrument throughout his career. Time-to-time Khan has been creating new ragas. While Raga Haafiz is dedicated to his father, Raga Rahat Jahan is devoted to his mother. A special one, Raga Subhalakshmi is dedicated to his wife, whom he surprised with this gift on her birthday.

Khan’s first marriage, arranged by his family, had failed. It was at a function in Kolkata that he first saw Subhalakshmi perform Bharatnatyam. The two happened to be at music gatherings thereafter. Besotted with her, Khan managed to meet her separately and found their thinking on the same wavelength. He proposed to her saying he would give her some months to take a decision. But he wooed her day and night, until she relented. They were married in 1976. Khan credits his wife for the heights he has touched in his career. The two have often been chosen for very select VIP gatherings.

The maestro recalls one such: “At an open-air function thrown in honour of Prince Charles and Princess Diana in Delhi, we were sitting next to the royal couple. I could make out that Diana was shivering due to cold. I immediately put my shawl around her and she felt so touched. Later, the Princess offered to return it to me, but I presented the precious shawl to her that had been with the family for decades.”

One of Khan’s career highlights include the US state Massachusetts proclaiming April 20 as Amjad Ali Khan Day in 1984. Apart from the several international awards, he has received honorary doctorates from many British and American universities.

Back home, he has been honoured with the Padma Shri in 1975, the Padma Bhushan in 1991 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2001. Recently, the Delhi government conferred upon him the Lifetime Achievement Award for his “outstanding, extraordinary and distinctive contribution” in his field.

Looking back, he recalls the journey when he was 12 years old. “I was invited to Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh for a performance. I got down at the station and kept waiting for the organisers, who were supposed to pick me up.

“After the train left, a man very hesitatingly approached me. He said he had come to pick up some Ustad Amjad Ali Khan. He was shocked when I told him it was me, as he had expected to see an old man!”

He adds, “Even after all these years, people mistake one musician for the other. Once at a store in Bangalore, while my wife was buying a saree, a man came to me and asked, if I was sitar maestro Pandit Ravi Shankar. I replied, ‘No, I am tabla maestro Zakir Hussain! Some refer to me as shehnai player Ustad Bismillah Khan.”

Committed to music, he has turned his family home in Gwalior into a musical centre. And has the desire to establish institutions in the West, especially in the UK and the US. “That’s because I feel that sarod has still not got the recognition it deserves. I want to make it as popular as the guitar and the violin,” he said.

Swiftly, I request him if he would mind strumming the guitar for me. The exceedingly humble man that Khan is, he picked up the instrument. Melody spilled everywhere, as he proved — music has no boundaries.