Tucked away on the edge of a vast coffee estate outside the bustling

city of Arusha, northern Tanzania, is Shanga, home to an extraordinary bunch of profoundly disabled Tanzanians who have transformed themselves and their environment in amazing ways.

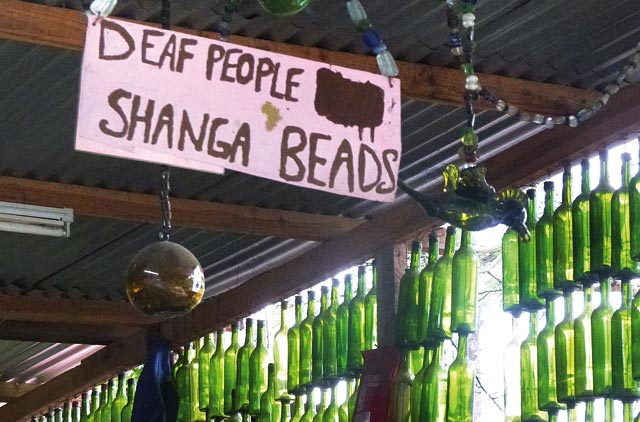

The lush ten-acre plot is the only business of its kind in Africa to train and employ hearing-impaired and physically challenged people to make jewellery and artefacts entirely from recycled materials.

The shop tinkles and shines with glass mosaic and walls of beads and bottles. Like their makers, they sit jauntily side by side, held together with a common thread. Even the pathways are inlaid with coloured beads leading through workshops stuffed with bright fabrics and fine craftwork. There is a tranquillity about the place and the gentle hum of contented industry. Here everything is something and everyone is someone.

It is the result of five years of work by Saskia Rechsteiner, the Dutch-born wife of a local estate manager. A tall, fair woman with a broad smile and boundless energy, she began the life-changing project by accident. “I had to make some necklaces for a Christmas fair and I had no idea where to start, so I copied a piece of jewellery I had using marbles and bits of fabric that belonged to my child,” she says. “I knocked up a couple of them to sell and the next thing I knew, the lodges and safari companies were asking for them and I couldn’t keep up.

“Our house girl’s hearing-impaired sister was living with us and she began to help me and the necklaces began flying out of the door. Through her I met and employed other special-needs people and slowly the word spread.”

A coffee shed was hastily converted into a workshop, and a restaurant and shop followed soon afterwards. All the materials used are from recycled products and all the profits go straight back into the project. “Even our machinery is made from rubbish,” beams Saskia, 41.

The generator, for instance, was created from an old washing machine engine and an alternator. A sewage pipe, a bicycle tyre and two old truck wheels are among the components for the operation, which services a worldwide market. Aluminium bottle tops, paper, cow horns and tyres are miraculously transformed into jewellery, mosaics and glassware.

Glass bottles, donated by hotels, lodges and restaurants, are crushed and smelted after which four trained glass-blowers create glass baubles and decorative pieces to be used for jewellery pieces.

Full of goodness

Today Shanga – the name means bead in Swahili – is an internationally recognised enterprise that employs 97 people and has a turnover of $60,000 (Dh220,386) per month.

It also has a restaurant where organic produce is used to prepare lunches served to visitors on their way to and from safari and the tourist buses that regularly stop there.

“There is a goodness here,” says Saskia. “People want to help but looking after special-needs people is a luxury in a country where so much needs doing.”

Saskia, born to a family in the flower export business, was schooled in Holland and studied in Paris and London. She employs people who are hearing impaired and some who cannot walk and their stories are truly moving.

“I remember the day Teresia came to me for a job. While there was nothing wrong with her, she had a severely challenged special-needs child, named God Bless, strapped to her back. Although he has never been diagnosed, he probably has severe cerebral palsy. She and her family were extremely poor and couldn’t afford to feed or take care of him properly. And since he needed constant attention, she doggedly carried him with her everywhere. At first sight, I guessed the boy to be about three years old, but was shocked to learn he was 18.’’

The boy was severely malnourished and his growth was stunted. “He comes to work with Teresia every day and lies contentedly on a carpet in the workshop playing with a ball,” she says. “For the first time, he is interacting with strangers and eating well. He has the most beautiful smile.’’

Saskia is sure the reason people buy their products is because they are attractive and not because they feel sorry for the staff. “You can’t sell on pity, not for long anyway.”

It’s clear that Saskia is very fond of the staff members of Shanga. Her empathy is deep, but beneath the fair, open exterior lies a woman who has learnt a few hard lessons.

“I was naive at the beginning, and I was robbed blind. Although I’ve been here all my life I thought everyone would see the big picture and what we are trying to achieve,’’ she says, shaking her head.

The project was jeopardised financially at least three times. “Then I got wise,” she says. “We are now a full-on profit-making business. We have scanners and barcodes and laptops. The staff all have salaries and bank accounts and with our guidance they become completely independent in everything they do.”

Helping people live without fear

Saskia’s commitment to Shanga is total, but with the joy comes a heavy responsibility and she admits it is not something she expected to feel so strongly about.

“Shanga changes people for ever, but I have sleepless nights over it. If the business fails these people can’t go back to where they came from,” she says. “A person with a disability is looked down upon in the community and is often treated no better than a dog by their family. Some have been locked away or used as slaves. They are never seen in public and are not deemed worthy of education. They end up being physically abused.

“Ironically, their fate doesn’t change much even when they get a job and a salary. They are abused again for the money they earn. So we negotiate with the families on their behalf and if they want to move out of the house, we help them. We rent rooms and get one hearing-impaired person, for instance, to share with a person who can’t walk. This way, between them they would be able to help each other and live a reasonably good life without fear.”

The whole ethos of Shanga highlights the lack of facilities for special-needs people in Tanzania and, having helped adults, Saskia has now turned her attention to the children. She visits schools and encourages teachers to teach mentally challenged and hearing-impaired children alongside the able bodied. It is groundbreaking work in Africa.

“If we can educate hearing-impaired kids early, they will become employable adults free from the stigma of having a challenge and be able to live independent lives. They won’t be a burden on the state or beholden to anyone else for their welfare.”

Saskia is overseeing the building of the first government secondary school for the hearing-impaired in Tanzania. She’d like to see more vocational training and more skills being brought in from overseas.

“There is no limit to what the hearing impaired can do, but it’s no good just throwing money at the problem. I’d like to see more skills coming in from Europe and America and much more vocational training. If a person can make something, they can sell it and buy food for themselves. It is a simple idea and one that shouldn’t be difficult to achieve.”

Now the project is secure, most people would take time to relax, and to spend time with their family. Not Saskia. Even though she has a husband and two sons, she can’t stop planning the future expansion of Shanga to help more and more special-needs people.

“I would like two more shops, perhaps at the airports. The workshops and restaurant are bursting at the seams so I am looking at a new site. In the next 18 months we hope to custom build the whole place from scratch. I still have a waiting list of over 200 people who could be working. I can’t not help them.”

Glancing around it’s easy to see the amazing transformation Shanga has made on everyone connected to it. The jewellery may be made with the rubbish that society throws out, but it shines like the smiles of those whose pride and purpose has been restored under the mantra “We are able”.

Inside Info

Visit www.shanga.org