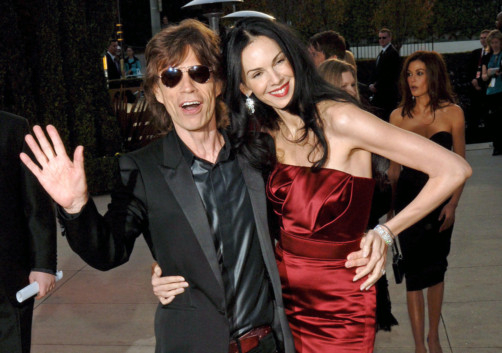

What makes a beautiful, successful and extremely rich woman take her own life? In lieu of any sort of evidence, the suspected suicide of designer L’Wren Scott is as baffling as it is heartbreaking for anyone who believes that depression is the sole preserve of the poor and ugly.

Unless, of course, you believe that a childless, unmarried woman has every reason in the world to be depressed.

It’s there in so much of the coverage, but one line in the Daily Mail sums it up: “L’Wren knew that Mick had no time for matrimony and little for monogamy. She seemed to be playing a long game. But after chalking up 12 years by his side, she could hardly be blamed for hoping for more.” Besides, despite renovating their multimillion-dollar Manhattan apartment 10 years ago to include “a nursery and nanny quarters, no baby ever arrived”.

Really, at 49, what else is a childless woman unable to convince her long-term partner to marry her to do but “plunge into depression”?

Mental-health workers and charities have struggled for years to get the rest of us to understand that depression and suicidal thoughts are not necessarily triggered by “bad luck”. But what much reporting of these tragic events shows time after time is a refusal to believe this, allied with the worst kinds of gender stereotypes.

This affects men as much, if not more, than women. A report by the Samaritans into the increasing suicide rates among men in 2012 posited the idea that, in the same way women must be in want of a child, men must be in possession of a good job. With figures revealing that men aged 40-44 were the most at risk of actually going through with rather than attempting a suicide, the report found: “Men compare themselves against a ‘gold standard’ which prizes power, control and invincibility.”

Last month, ONS figures revealed that, in 2012, 4,590 male suicides were registered in the UK, compared with 1,391 female — the biggest gap for 30 years.

By analysing each of these deaths, the report drew some conclusions in a field riven by confusion. Two facts stand out. The first is that deprivation and poverty have some impact on rates of suicide: so, men in the lowest socioeconomic group living in the most deprived areas are approximately 10 times more likely to kill themselves than men from more privileged socioeconomic backgrounds living in the most affluent areas.

The second is that around 90 per cent of people who kill themselves have been suffering from a psychiatric disorder at the time of their deaths.

In some ways these facts could contradict each other is it mental illness or poverty that leads to despair? But isn’t it possible, instead, to see them as linked: that those living in poverty, in deprived areas, are less likely to have received the mental-health help they need before taking their own lives?

Suicide, almost impossible to comprehend by those without mental illness, then becomes a blame game, as we clutch at straws to explain why someone could have ended their own lives. If that person seems to have everything that money and beauty can bestow, then the easiest thing, especially for journalists chasing deadlines and with huge amounts of space to fill, appears to be to fall back on stereotype.

To be fair, several news reports following L’Wren Scott’s death suggest that financial worries might have been at the heart of the problem. None of us can really know the impact of corporate losses of £3.5 million (Dh21 million) on a fashion designer with multiple homes and rumours of a lucrative new deal. Instead, reports point out how proud she was of having her own business, especially when Scott could so easily have gone with the moniker of “Mick Jagger’s girlfriend”.

Around 4,400 people kill themselves in England each year — that’s one death every two hours — and at least 10 times that number attempt suicide. Perhaps the quicker we give up this facile gender-based understanding of happiness women need children and a husband while men need to work — the better it will be for us all.