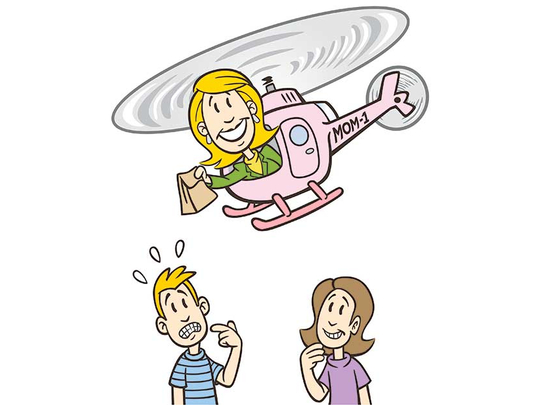

Helicopter parenting, or over-parenting, is a recurring theme in recent books and articles. From the book “How to Raise an Adult,”by former Stanford Dean of Freshmen Julie Lythcott-Haims, to the recent article Tips from a college president for a healthy relationship with your college student, by Jonathan Gibralter, educators are chiming in to advise parents on how to maintain a healthy relationship with their college students.

Gibralter, president of Wells College, wrote:

“Parents must allow their children to adjust their studying habits to meet the increased rigor, work for grades they deserve and find their own voices should self-advocacy be necessary. This means parents should not call the professor if their child receives less than an A on an assignment, not petition a final grade with the dean or president, and not supersede their child’s choice of courses or professors.”

While these ideas are both appropriate and helpful for parents of college students, it could be argued that the message needs to target parents of younger children, as well. If the goal is for children to successfully manage life after high school without the constant assistance of hovering parents, healthy habits need to be established long before age 18. Perhaps the ideal time to offer parents suggestions for maintaining healthy relationships with their children is when children enter elementary school.

Most people do not plan to become helicopter parents, nor do they wish to overparent their children. Parents know and love their children and have their children’s best interest at heart. They are motivated to provide their children with access to safety, happiness and success. Yet it is in the small moments of subtle communication of expectations throughout childhood that children learn the habits and values that remain ingrained in their behaviour.

I recently witnessed one such small moment for a 6-year-old boy at a sporting event. His father suddenly noticed that the son’s shoe was untied.

“We are going to run over to the other side of the track so we can see better,” he informed the boy. “But before we go, I need you to tie your shoes.”

The father then stepped to the side and patiently watched as his son painstakingly tied his own shoes. It would have been much easier and faster for the father to tie the shoes, but he demonstrated restraint and allowed the boy to do it on his own.

In another small moment I observed, two children began bickering at a local park. “I had it first!” “No, I did!” Their mother eyed them suspiciously, on guard for a possible physical showdown. After a few moments of tension, the children worked out a solution on their own. The mom was alert, ready and available, but by giving the children time and space to work things out, she gave them ownership and agency in their development.

When adults step back and give young children time to identify and solve problems, they provide the opportunity for children to learn and develop important skills such as self-regulation, empathy, problem-solving, creativity, tenacity, perseverance and patience. Parents who maintain healthy relationships with their young children while offering supportive opportunities for children to grow and develop these important skills often have the following traits in common.

- They listen to their children. When parents listen to their child before formulating a response, it allows children to develop their points of view. That teaches them that their voice has value and that they are capable of self expression. When other adults interact with their children, these parents encourage the children to respond for themselves. They make an effort to allow their children to speak and finish their thoughts before speaking on their behalf.

- They ask their children, “What can you do to solve that problem?” Follow-up questions might include, “What have you done so far? What worked and what didn’t work?” Later they might ask, “How can I help you solve that problem?” That sets the stage for children to come up with possible solutions. Parents can further help by coaching children through the implementation of their problem-solving plan; by practicing with role playing; and by encouraging them to speak up and self-advocate from an early age.

- They give time for problem solving and wait before intervening. More often than not, children can and will think of ideas to try to untangle themselves from predicaments.

- They respect and support teachers. When parents are aware of teachers’ goals and watch how they interact with students they may notice the expectations for children in their child’s current grade level. This is valuable because although parents have great expertise on their own children, teachers have many years of experience with that age group. Teachers and other caring adults in the lives of children are teammates working toward a common goal, not adversaries.

- They permit natural consequences to run their course by regarding setbacks as learning opportunities. Failure and disappointment are a regular part of life from childhood to old age. When children are given the opportunity to deal with setbacks early, within a loving, supportive context, they build skills that will help them later in life. When a child loses a board game, he can learn about good sportsmanship. If children do not secure a spot on the best team, or if they are passed over for a starring role in a theater production, they may learn to deal with disappointment and work harder to try again. When a child misses a birthday party or play date, her empathy toward others may increase.

Children who are given opportunities to develop their voices and take charge of their learning and behavior, by parents who incorporate these positive practices, will be well-equipped to deal with challenges. Children of all ages need their parents as positive role models to offer love, support, encouragement, safety and shelter. Kids are capable of learning, speaking, choosing, doing, trying, failing and trying again, knowing that their caring, supportive parents are right beside them, encouraging them to move forward to bigger things.

Merete Kropp is a child development and family specialist and mother of three. Kropp can be found at familynurturance.com and @nurturance on Twitter and Nurturance on Facebook.