The most telling moment on the debut album by the young soul singer Khalid, American Teen, comes at the end of the title track, which opens the album. The song begins with a beeping alarm and new-wave drum-machine slaps, then veers into a story of light youthful indiscretion: “I’m high up, off what?/I don’t even remember/But my friend passed out in the Uber ride.”

Khalid is singing all this casually, without judgement or emphasis. He only starts vibrating more intensely in the second verse: “I’ve been waiting all year/To get the hell up out of here/And throw away my fears.”

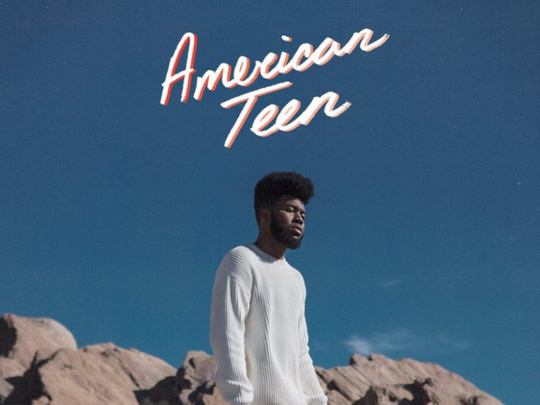

Khalid graduated high school last year — he’s 19 now — and he’s nailing the fitfulness of knowing the bright options the future might hold while still being stuck in school, or in his hometown, or in the frame of mind that tells you to do only what’s expected of you.

That’s an almost universal teen conundrum, something Khalid acknowledges throughout this song with constant use of “we” and “our” (“We don’t always say what we mean,” “This is our year”). He’s sketching a generational mood, and drives the point home when at the end of the song, the digital shimmer falls away and, backed by only an acoustic guitar, a group of young men — high school friends from back in El Paso — bark-sing Khalid’s chorus. It’s a campfire singalong, a signifier of tactile humanity for a singer who knows how technology both redeems and corrupts.

American Teen is a promising amalgam of bedroom art-soul and 1980s new-wave pop maximalism, and a union of lonely-boy mirror gazing with a sense of larger cultural purpose. It most vividly recalls the promise embedded in the soundtracks of John Hughes films — that an outsider’s story might in fact be the thing that can unify and move millions.

The musical nods to that time are heaviest on the album’s first half, which is almost sugary in its commitment to the synthetic. What grounds it is Khalid’s singing, which unfolds in slow, syrupy drops. He doesn’t sing with power, only internal grace and calm, even when he’s just blowing off teenage steam, like on 8TEEN and Let’s Go. Some of his songs, like Coaster and Hopeless, are elegantly structured enough to be delivered by a Sam Smith or an Adele, but the production on this album — most notably by Hiko Momoji and Syk Sense — saves Khalid from square corners and sharp edges.

Mostly, he muses over connections that are on the fritz. “I’ll keep your number saved/’Cause I hope one day you’ll get the sense to call me,” he sings on “Saved,” then, contemplating how long that might take, pivots: “I’ll keep your number saved/’Cause I hope one day I’ll get the pride to call you.”

This, like a few other songs here — Khalid wrote almost all the lyrics on the album — are worthy additions to the body of music about how technology and love overlap. Location is a prime example of that — a song about begging for his lover to drop a pin and give him coordinates. Here, he wants to take flirtation from the virtual to the tangible: “I don’t wanna fall in love off of subtweets so/let’s get personal.”

The sultry Location was Khalid’s breakthrough — a hit on Kylie Jenner’s Snapchat, naturally — but it’s not totally representative of his approach, which tends to operate in that space between bluster and reserve.

In that way, and also in his delivery and production choices, he’s part of a larger remaking of R&B — an inheritor of, in different ways, the Weeknd’s early narcotic mixtapes; the light romantic gloom of Bryson Tiller’s debut album; Sampha’s vulnerability; and, of course, the long tail lite-anarchism of the Odd Future collective as experienced through its R&B progressives The Internet and Frank Ocean.

That comfort with and dedication to youthful ennui is emerging in several places at once lately. It’s there on the beautiful American Boyfriend: A Suburban Love Story (Brockhampton) released late last year by Kevin Abstract, a wildly ambitious singer and rapper with strikingly subversive pop instincts. And London O’Connor’s debut album, which was self-released in 2015 but recently re-released in remastered form on True Panther, is a dizzying, entrancing ramble through genre and style, full of naive, ecstatic singing and smartly distracted raps. (Love Song even recalls the psychedelic hippiedom of P.M. Dawn.)

For O’Connor, like Khalid, the uncertainty of youth is a potent muse. The happily lost subjects of his single Nobody Hangs Out Anymore — “All my friends are on the net, and all my friends are in the net and all of us are out of it and none of us are into it” — are kin to Khalid’s meandering teens. They might as well be the ones at the end of American Teen, shouting along to that guitar: “My youth is the foundation of me/Oh, I’m proud to be/American.”