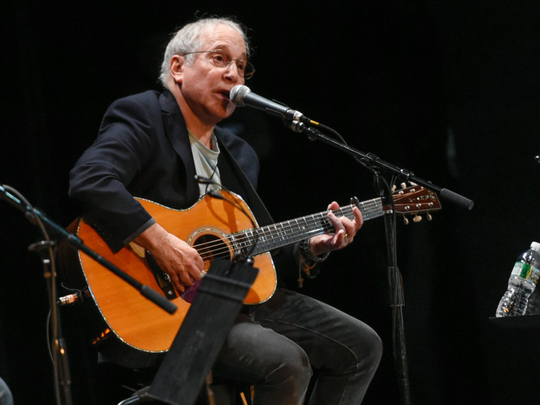

Look at the liner notes on Paul Simon’s new disc, Stranger to Stranger, and it seems like a laboratory of exotic instruments. Musicians use a mbira, a bamboo marimba, cloud chamber bowls, a chromelodeon, a zoomoozophone — and a cheap clock.

It’s an album as notable for its sound as its songs, without the feel of an academic exercise. Simon, at 74, is more adventurous musically at an age many peers are content to ride on their reputations.

“There’s no point in resting on laurels,” said Simon, whose Manhattan office displays both of his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame trophies side by side. “You’re either interested in an idea, in which case you pursue it, or you have no ideas or aren’t interested in pursuing ideas. ... Rest is indicated by a sign on a staff.”

Busting beyond his folk-rock roots is not new for Simon, an impulse that has become more pronounced in the past few decades following his work with African musicians on Graceland and Brazilians in The Rhythm of the Saints. It hasn’t always been smooth; the success of Graceland opened a debate about cultural appropriation.

“It’s not like I set out to explore,” he explained. “There’s a connection that I’m following that pushes me toward some pleasing sound that I can barely imagine, so I go looking for it.”

For the percussive Stranger to Stranger, which is out now, Simon was initially intrigued with flamenco music and the use of hand-claps. Through his son, Simon met and collaborated with Italian producer Digi G’Alessio, who records under the name Clap! Clap! Old recordings of the vocal group the Golden Gate Quartet are used to ghostly effect. But Simon’s most intriguing journey took him to Montclair State University in New Jersey.

At the time Montclair housed a collection of instruments created by the late Harry Partch, a composer who worked with instruments that had smaller tuning differences than is typical. Simon brought a portable studio in to record instruments like the cloud chamber bowls — glass-shaped bowls that hang from a wooden frame and produce a haunting sound, said Robert Cart, director of Montclair’s John J. Cali School of Music.

“I wasn’t surprised that if there were a pop musician who was interested in the instruments, that it would be Paul Simon,” he said.

Simon was the only popular musician to explore the Partch instruments in the 15 years they were housed at Montclair, Cart said. They’ve since moved to the University of Washington following a caretaker’s death.

Simon believes he has an unusual songwriting process, connecting sounds together to see if they fit and bringing in lyrics later. Here, his observational songs muse on mortality, mental health, insomnia, romance and an overzealous security guard.

In Wristband, the narrator is a musician who sneaks out of a concert hall for a smoke and isn’t allowed back in because he lacks the evidence that he belongs backstage. Together with The Werewolf, they contain a quality not always present in music: humour. The Milwaukee man he describes in The Werewolf had “a fairly decent wife,” he sings. “She kills him — sushi knife.”

“I’ve always had that in my music,” he said. “A lot of it has been in there and people don’t know that I’m kidding. My mind works in comedy a lot but my voice is not a comedic voice.”

Later in the album, Simon guesses that it took dozens of takes for him to get the right read on a 12-letter obscenity that the song Cool Papa Bell even concedes is “an ugly word.” The very surprise of it alters the song’s mood.

Simon is heading out on tour, crafting a show with a mixture of the old and new. He understands the need for crowd-pleasing favourites, even for something he doesn’t particularly like (You Can Call Me Al). There are enough new songs from the past decade that go over well in concert, he said.

He’s toured with Sting and done a Graceland reunion tour over the past few years. Don’t expect any reunions with estranged partner Art Garfunkel. “I would have been happy enough to sing with Artie if it would have been pleasurable,” he said.

When he finishes a new disc, Simon wonders whether it will be his last. But then the cycle of creativity begins again.

“Six months later you have an idea, and you do begin,” he said. “That’s happened to me my whole life. From that, I infer that it’s part of my nature to do that. But it’s not an automatic thing that will happen forever.”