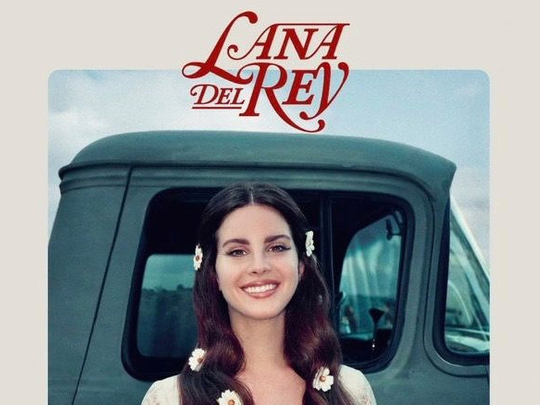

Lana Del Rey is smiling on the cover of her new album. Quite the radical move considering her default expression has ranged from seductive glower to wounded pout. Such is her brand loyalty to pained poise and misery, the joyful precision on Del Rey’s 2017’s face seems almost ironic.

According to a recent interview with NME, however, the smile is symbolic of a new artistic chapter. It was her goal, she says, for this album to mark a “moving-on-ness from wherever that other place was that Honeymoon and Ultraviolence came from. I loved those records, but I felt a little stuck in the same spot.”

For those who haven’t paid attention to Del Rey’s career since its first flourish — the sighing, sorrow-drenched Video Games — the Californian artist’s music has remained locked within a small range of emotions, most of which revolve around awful men (often elderly bikers or gangsters) doing awful things and Del Rey remaining belligerently in love with them.

However, the world has changed considerably since 2015’s Honeymoon, and, much like Katy Perry ‘s ambition to make “purposeful pop”, Del Rey has decided to puncture her long-running narrative and reflect the troubled times we are in.

Here, her political approach is rooted in escapism. Del Rey’s longtime producer Rick Nowels recently declared When the World Was at War We Kept Dancing a “masterpiece” for its lyrical message about finding pleasure in the current political climate.

Meanwhile, Coachella — Woodstock in My Mind is a sedated trap track; one that attracted derision for its title, given that Del Rey is the patron saint of wearing a flower garland at a celebrity-filled festival. It is a sweetly innocent song about observing an audience of young girls dressed just like her, and praying for their safety amid a period of global terror.

The triumphant God Bless America was written before the Women’s Marches of earlier this year and is a response to the Republicans’ attack on women’s rights — a relief for parents who’ve fretted over their children’s obsession with a singer who has a habit of romanticising toxic relationships. (Del Rey recently admitted that she no longer sings the Crystals-sampling lyric, “He hit me and it felt like a kiss” from her song Ultraviolence.)

You can hear the pleasure in Del Rey’s vocals on Beautiful People Beautiful Problems, a piano ballad she shares with Stevie Nicks, which is comparable to Harry Styles’ vague, state-of-the-nation balladry.

But, for every socially conscious sentiment, she paints another pastel coloured paradise full of feted actors (“I’m flying to the moon again / Dreaming about heroin”), doe-eyed infatuation, and 50s girl-group appreciation (“My boyfriend’s back... and he’s cooler than ever”).

Groupie Love is spoken from the perspective of a devoted fan and features quintessentially Del Rey-like lines such as: “This is my life, you by my side / Key lime and perfume and festivals.”

13 Beaches is inexplicably about the time Del Rey travelled to 13 beaches before she found one with nobody on it. It’s surface-level stuff, but perhaps there’s a deeper message in there somewhere: the overwhelm of fame? Overpopulation? Climate change?

Still, Del Rey’s music has always been more about a feeling than an explicit lyrical message. This album features some of the most sophisticated production and shifting of moods from her four-album career. A$AP Rocky and Playboi Carti feature on the lazy rap track Summer Bummer, its eerie production and futuristic melancholy sounding closer to a track from Frank Ocean’s Blonde than her usual 50s and 60s enthralled shtick.

The Beatles-referencing Tomorrow Never Came features vocals by Sean Lennon. It’s a strange, melodic reworking of the Beatles’ Something, a vintage glow that rubs up against the sleek contemporary-sounding soundscapes elsewhere. The Chris Isaak school of monochrome melancholy echoes around icy production.

The old and new entwine throughout. While many of the song titles and clumsy references may have a discerning music fan scoffing at Del Rey’s predictability, there remains an admirably unflinching quality to this record (even if it is five tracks too long). She has evolved elements of her once disturbing narrative, and her ardent fan base will detect clear leaps made since her debut. But, in the current climate of laborious genre-hopping and guest vocals on throwaway chart tracks, Del Rey has remained a mystery. She is consistent in her aesthetic, adding zeitgeisty elements to her sound without being dictated by them. And for that reason she exists in a lonesome, luxurious league of her own. It’s not why she’s smiling, but it should be.