Long-shot wins, unscripted moments and strange celebrity interactions are among the best reasons to watch awards shows like the Grammys. The album of the year category is where they turn up surprisingly often.

“What the hell?” Win Butler of Arcade Fire blurted after Barbra Streisand hesitantly announced that The Suburbs had won the Grammy as album of the year for 2011. It was the last award at the end of another long slog of a Grammy night, and if viewers weren’t fatigued enough, Arcade Fire had just played a song from The Suburbs, Month of May, in a misguided, disjointed, perhaps punk-intentioned barrage of strobe lights while some guy on a bicycle circled the band.

No matter: For once the album of the year went to music that was new, independently released, not hit-driven, praised by critics and, well, worthy of the award. Across a swath of the music business, there was a collective double take and the question, “Arcade who?”

Album of the year has often been the Grammy voters’ generational revenge category: Revenge on the kids with their cheap (actually expensive) pop thrills, revenge on the musical illiterates with their hit-making computers, revenge on those who think in terms of files and playlists rather than albums as artistic units. Two other top Grammy categories — song (for songwriters) and record (for performers and producers) of the year — regularly go to hit songs; best new artist tends to be someone who had one of those hits, though not always. But album of the year is the bastion of artistic prestige, or maybe the line in the sand.

The Grammy voters won’t turn their backs on an unstoppable (and musically impressive) blockbuster like Adele’s 21, Michael Jackson’s Thriller or Norah Jones’ Come Away With Me. But they can also treat album of the year like a lifetime achievement award, as they did with Steely Dan’s Two Against Nature in 2001 (beating Eminem and Radiohead) and Beck’s Morning Phase (beating Beyonce) last year.

I’ve had pretty good results by predicting that the album with the oldest songs will win, from Natalie Cole’s Unforgettable ... With Love, Eric Clapton’s Unplugged and Tony Bennett’s MTV Unplugged in the 1990s through O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Ray Charles’ Genius Loves Company, Herbie Hancock’s River: The Joni Letters, and Robert Plant and Alison Krauss’ Raising Sand in this century. They just don’t write ‘em like they used to, Grammy voters grump.

Another factor is the employment of studio musicians (and Grammy voters), particularly in Los Angeles, which may have tipped the scales for both Toto in 1983 and Daft Punk — which obviously saw the light after its inhuman, electronic production sins — in 2014.

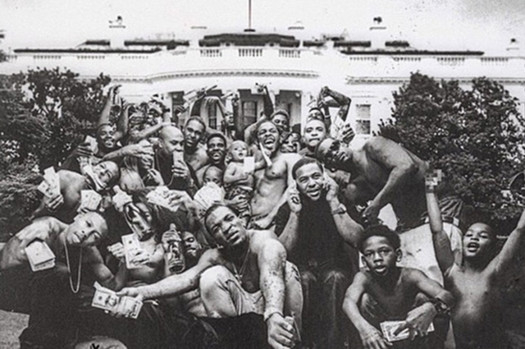

But neither element looks decisive this year, with five albums of all-new songs. The nominated albums by Taylor Swift and the Weeknd both rely on producer Max Martin’s close-knit hit factory; Alabama Shakes is self-contained; Chris Stapleton, the Country Music Association’s big winner this year, recorded his entire album with one band. Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly does use a broad assortment of musicians, including some jazz headliners and some studio stalwarts. It would be a marvel if that helped Lamar’s dense, forward-looking, breathtakingly ambitious hip-hop album prevail over its much poppier competition.

How did Arcade Fire win album of the year? It’s still a mystery. Among the other nominees in 2011, maybe Lady Gaga and Katy Perry split the hit-loving pop vote; Eminem’s Recovery was a letdown despite his brand maintenance; and Lady Antebellum hadn’t thoroughly crossed over from country. Arcade Fire is still a band playing its own instruments and very respectful of the album as an artistic form. Regardless of how it happened, Arcade Fire made the most of its astonishment.

A thank-you list had clearly not been prepared; Butler also dropped a flabbergasted “Holy [expletive],” and then, by all accounts impulsively, announced, “We’re gonna go play another song ‘cause we like music.”

Streisand and Kris Kristofferson said flustered good nights as the band headed for its instruments; fans rushed forward as, presumably, much of the VIP audience exited for the after parties. Butler set his Grammy on an amplifier and, newly anointed by the music business, plunged into Ready to Start.

“Businessmen drink my blood,” he sang, sweaty and grinning, “like the kids at art school said they would.”