The limiting factor here, was me. In a Ferrari 458 Italia, hot turbocharged Porsche, or an all-wheel drive Nissan GT-R, the grip levels are such that you will never exceed them on public roads unless your family name is Alesi, Röhrl, or Tsuchiya. But the limits in these cars sneak up on you like in a game of tag, and when you’re it, you’re actually deep in it. So it was me who ruined this story from the beginning, and failed to test the McLaren MP4-12C Spider’s dynamic confines. The problem is, there are no confines. Well, other than the Dh1 million confine to ownership.

My track experience taught me that this car is faster than my brain, and the road drive section demonstrated that a supercar can indeed rearrange the features of your face. A week later and I’m still drinking my morning latte through a straw inserted in my ear. Yet the limit is quantifiable in the 12C Spider. Everything is quantifiable in the 12C Spider. That’s just it. You can understand it, there are no secrets; it won’t throw you off a cliff. The only thing that is quite a no-no, really, is lifting off the throttle abruptly in faster, transitioning corners. Then you will feel the redeeming freedom of spinning around your own polar axis at 200kph — I hear it’s quite liberating.

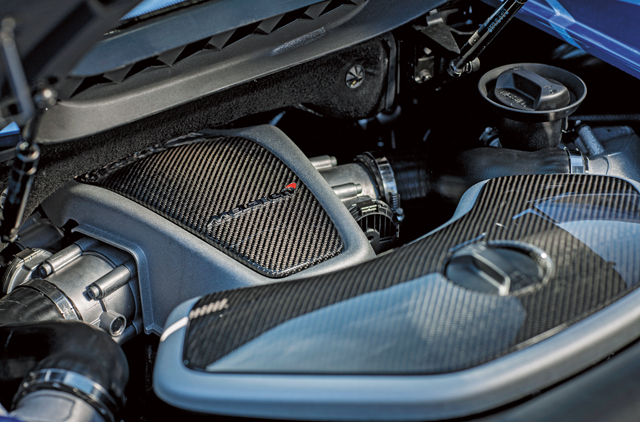

But I take the advice on hand and every time I see a bunch of fast corners, resolve to stay flat to the floor. It worked. I’m still here. Although my nose flew off somewhere into an Andalucian olive orchard… Everything is so simple at its core. Carbon is in everything. It’s graphite, it’s diamond, it’s in humans, animals and plants, and it’s in McLaren MP4-12C Spider chassis. This 75kg MonoCell monocoque (figures from 75kg to 85kg are bandied about, but McLaren’s perfected the manufacturing process over the two years and it’s now officially 75kg) is the defining feature of the car, more so even than Woking’s bespoke 3.8-litre twin-turbocharged 616bhp V8 engine. The chassis is Genesis.

The carbon fibre MonoCell makes the Spider the only car in class and this price range to feature such a racing-derived design, with McLaren also having introduced carbon monocoque tubs into Formula 1 over three decades ago. The legendary 1992 McLaren F1 was another breakthrough for the company, as the first road car to use a carbon chassis. Gordon Murray’s team back then used to take 3,000 hours to construct just one of the 100 or so F1 chassis. Today’s one-piece moulded 12C Spider MonoCell takes three hours to make. Progress is relentless with McLaren, whether it’s behind closed doors in the spotless cleanrooms, or in the open world as the 12C Spider launch-controls itself from rest to 100kph in 3.1 seconds.

As impressive as the front and rear aluminium sub-frames are, along with the active aerodynamics, stupendous bespoke Pirellis, ProActive Chassis Control orientated around the car’s double-wishbone suspension design, and an engine that weighs just 199kg, really, the origin of everything that’s so brilliant about the 12C Spider is that 75kg MonoCell. Everything external acting on the car — the road, the camber, the centrifugal force in the turns, everything you’re not physically inducing onto the car yourself — isn’t upsetting any single component of the McLaren Spider and throwing things even slightly out of balance. This entire creation of carbon fibre and aluminium tackles the tiniest outside influence on its consolidated whole as one solid object.

The Spider doesn’t feel bolted together so much as it feels fused by forces of nature, or something. What in the world do they get up to in those Woking cleanrooms, and what sorcery is at play there? It seems now there are cars with carbon monocoque chassis, and those without. You either are or aren’t. The 12C Spider most definitely are… is. The Spider was in development in tandem with the Coupé. The only reason why it’s out more than a year later is because the company had to give the Coupé a fighting chance, as McLaren expects the Spider to command 70 per cent of all 12C sales, and perhaps more in its first year of production. So if you’re already signing the cheque for over one million dirhams, you’ll be happy to know your choice is hardly compromised at all.

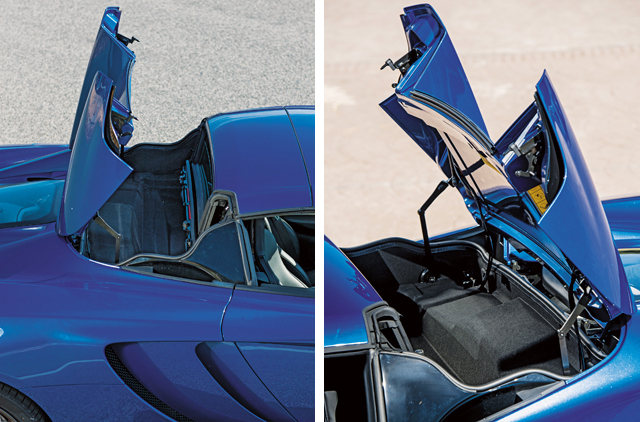

The 1,474 kg Spider weighs more than the Coupé, sure, but that’s because it features an electrically lowering and closing roof (up or down in 17 seconds, on the move) that only raises heft by 40kg, thanks to lightweight composite materials used in the construction of its two panels. There’s also the 2kg added due to the Spider’s unique exhaust system, necessary because the Coupé’s exhausts sounded rubbish with the roof down. These ones definitely do not sound rubbish. Another novelty exclusive to the Spider is the roll-over protection system integrated into the rear buttresses, which saves both weight and complexity compared to a typical active pop-up system. Lastly, there are the climate control and audio systems, which have been rethought and recalibrated for top-down motoring.

British high-end audiophiles at Meridian took care of the sound — although I like to think that the 3.8-litre V8 already sorted that out — while the air conditioning system now automatically adjusts airflow to the lower cabin vents when the roof hits the deck. Oh, and before I forget, there is now also a rear window — sort of a wind buffeting piece — that you can drop down regardless of the roof’s position, meaning you can bask in the engine’s wail whenever you want, which is always. At 220kph plus with the top down, whether that little wind buffer is up or down makes no difference because it’s deafening in the cabin. At regular highway speeds, however, the rear window is especially useful on tunnel runs.

Some of the tunnels on the route through the Andalucian hills are just half a kilometre long, so it takes a hard stop from seventh with some whack to second, bursting near the red line with the concoction of boiling noises behind you ready to explode, and then it’s into the tunnel and the accelerator is down, and the walls resonate and literally shake you up; same through third, snatch fourth, and you’re out. Remember to breathe again. The Spanish roads in this region have obviously been on the receiving end of some lovely, crisp Euro notes. They’re mostly new, smooth and designed by a fervent motorsport fan, with some patches left abrasive for the added challenge and maybe the worth of tradition: sort of like why they refuse to remove the yard of bricks at Indianapolis.

Before the track drive at the Ascari Race Resort, McLaren has thoughtfully marked all cameras on the road section with ‘atencion’ in red and warned us about some zealous local Guardia. Good to know, because I don’t have my international driving licence with me anyway. The thing quickly evident with the Spider is how it handles the seemingly unsettling. When crests sneak up on you and you need to adjust the steering over the top as the car gets light, or the suspension compresses in shadow-hidden dips in the middle of turns, that’s when the car almost predicts the unbalancing act and spurs itself for the change of conditions so that you don’t have to do the bulk of the work.

Those sensations of powering through mini Eau Rouges on the public road, or cresting your own Nordschleife’s Flugplatz on the A367 from Ronda to Ascari, are all there. The drive is epic. If it was a dog, the Spider would not be a feisty pit bull barking and tugging at its leash. It would be an obedient Rottweiler only concerned with his master’s safety. Be warned though, it hasn’t been neutered. The steering isn’t loaded with forced heft; it remains light with just enough resistance to keep the wheel in place if you let go with your hands, as the wide tyres tread over the tarmac gripping a path before succumbing to any tram-lining. That sort of thing doesn’t happen with the Spider, it just finds assured grip wherever you put it.

And because you are seated so perfectly with zero offset with the pedals or the wheel — I think I faintly remember this is how nice and cosy a womb was — you can clearly see the haunches of the wheel arches enclosing the P Zero Corsa tyres, and use apexes for target practice. Just pick them off with perfect accuracy, and when the road tightens beyond that fallen rock jutting onto the surface, you can flick your wrists in an etiquettal teacup hold, and the McLaren Spider will just as elegantly and deftly skip around the problem.

All right, there is a flaw with the optional electric seats, which is that they are mounted too high. The manual driver’s seat pins you down lower, crucial for the ideal view out of the windscreen, and more importantly allowing your backside to be even more embraceful of the rapidly rolling road below. Remember that for the options list, and your bum will forever be indebted. The gearbox is identical to the Coupé’s, and isn’t really too concerned when you ask it to skip a couple of gears on the way up with the paddles. Then again the car’s life-giving ones and zeros have been arranged by McLaren Electronics, a member of the Group that supplies the digital brains to the entire Formula 1 grid, as well as the Nascar series and Indycars.

I think maybe that kind of brain knows better than mine how many gears to skip. (What was I thinking anyway? Why would I want to skip gears and miss the rev limiter’s bounce?) When snapping down in the Graziano ’box, the car heaves on the slight overrun, you press into the seatbelt and exhale, the turbos let out a hiss, the exhausts burp, and the cleansing is complete. Accelerating towards the next hairpin is accompanied by a gush of power, and you’re in a hurry to get there as much for the thrill of frightful acceleration as for another opportunity to brake hard and wiggle the rear end, with the pipes loudly burbling and gargling unburnt fuel and spitting out in disgust. It’s the glorious sound of having so much power, you’ve got some left over to throw away.

At Ascari, the 12C Spider behaves over its kerbs like it behaves over public road rumble strips. Coming out of the fastest corner on the track where you don’t even have to lift but I do anyway, I turned in too late and made it wide on the kerb kicking up some dirt on the way out, and I hardly moved in my seat. I came here not knowing what to expect. I leave knowing that McLaren has as much passion for excellence and automobiles as anyone else that’s been in the game for decades. On the way over in the plane I was reading about Ron Dennis, chairman of McLaren Automotive, and he admitted that a passionate image is something this young carmaker still needs to exalt.

But it sort of has already, and long ago. Come on, this is McLaren, with victories in Can-Am, Le Mans, Formula 1, Formula 5000, GT3, and a winning ratio at the top of the game of one in almost every three Grands Prix. McLaren is practically bursting at the seams with passion, for excellence and success. For those who know what this racing engineering legacy has achieved and the innovations it’s brought along, the endeavour is clearly there; the passion to be the best. And, like everything else about this astounding car, this fact is also quantifiable; the 12C Spider is the best.