Baghdad: The crowds were so large that we had to approach Mutanabbi Street from the river, coasting across the Tigris in a small wooden motorboat under grey skies.

After disembarking on the docks below a statue of the 10th century Iraqi poet Abu Tayeb Mutanabbi, we climbed a flight of stone steps to the marketplace of booksellers lining the narrow pedestrian way.

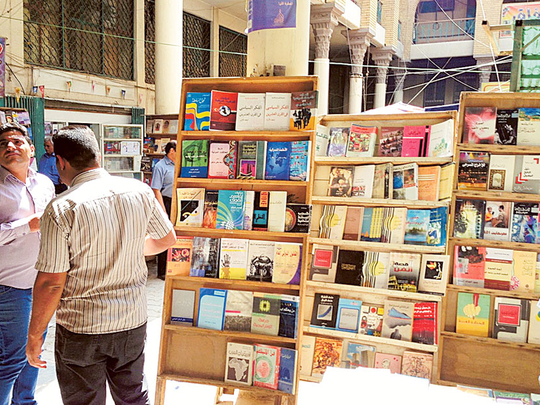

Mutanabbi Street has become an intellectual oasis once more: The weekly book market felled by a car bombing seven years ago that took 26 lives again teems with literate patrons.

A few steps from the statue, dozens lined up to enter the open-air courtyard of a cultural centre where writers gather weekly to share their work. Up the street, the Shabandar Cafe was packed with patrons — young and old, mostly male but a few female — sharing their latest finds over tea and water pipes. They sat sipping and smoking in small wooden booths beneath walls papered with black and white photographs of Iraqi intellectuals.

Outside, old men sold sesame-covered pretzels called smeed, and young men squeezed fresh pomegranate and citrus juices. All along the street of brick storefronts supported by ornate columns, booksellers spread their wares on the ground or in low makeshift stalls. Those perusing said that in a city and country still on edge — where militias lurk, car bombs explode and the threat of Daesh militants is ever present — the book market is a welcome respite.

Among the readers on hand was Mohammad Baghdadi, 32, a manager at the Ministry of Trade. Baghdadi, clean-cut with a pressed sweater and leather shoes, said he favours writers like the late Iraqi sociologist Ali Wardi and American thriller writer Dan Brown. He has read every book Brown has written except the seemingly elusive ‘Digital Fortress.’

“Baghdad is a historic city, still one of the highlights of Islamic civilisation,” the civil servant said as he searched for a paperback copy of the late-1990s book, which awaited him a few stalls away.

Mutanabbi is crammed with the highs and lows of civilisation. Gold-embossed Qurans are hawked alongside pirated DVDs. Customers snapped up the latest by Baghdad poet Adhem Adil, but also Danielle Steel. One rack displayed “Sarah Palin: An American Story” next to “America,” by “Daily Show” host Jon Stewart and a psychology manual titled “Understanding Human Behaviour.”

Civil engineer Mustafa Shahbaz, 26, came looking for science and science fiction books, and was glad to see the peaceful city he has long known, instead of the Baghdad of bombings and shootings.

“Baghdad has a hidden face” that’s difficult to see from afar, he said.

“When you see all these people coming, you don’t feel you’re in danger. Where there’s a culture of reading, there won’t be war,” said filmmaker Salaam Mousa, 30, considering the crowd from behind mirrored sunglasses and a fur-trim coat, before taking a call on his smartphone.

Unknown to them at the time, several bombings had been reported in other parts of the capital that morning, killing 11.

Etihad Naji, 56, a middle school geography teacher, has come with her two daughters to the book market for years. Their custom is to gather bags of books, then visit the river and the Baghdad Museum.

“There are educated people who are interested in culture. The situation is not stopping them,” Naji said of the continuing violence.

Naji wears a headscarf, but her daughters do not. One is a lawyer, the other a landscape designer. Mutanabbi has helped them grow more self-confident and empowered, they said.

“We see other women, but not too many,” said Sofia Naji, the lawyer, “Some families are conservative and don’t let women go out.”

Nahla Nadawi, 48, who teaches Arabic at the College of Education for Women at the University of Baghdad, was with her 13-year-old son. Nadawi, with bobbed hair and a sleek suede swing coat, searched the crowd streaming past for young faces, especially those of young women, but found few.

“Look, look. It is old. How many youths can you see?” she said, “The younger generation reads less. Youths like to read electronic books; books are very expensive on their budget.”

The majority of new female students she encounters have never read a book that’s not religious, she said.

There’s a saying: “Cairo writes, Beirut publishes, Baghdad reads.” But that’s not true anymore, Nadawi said.

She looked around. Communists were waving flyers and shouting to the crowd. Human rights activists were passing out their newspaper, Freedom. Government workers were marching for improved wages and benefits.

Mutanabbi Street has always been a hotbed of dissent. Under the long leadership of Saddam Hussain, antigovernment cells published and sold illegal copies of their tracts here under fake names. After Saddam fell more than a decade ago, dissidents gathered in Mutanabbi as successive administrations rose and fell.

“Politics are going to take over our very air!” Nadawi exclaimed, laughing ruefully.

She preferred the old, comfortable book market of years past. But she accepted that in Baghdad, change is not only inevitable, but necessary.

Seven years ago, her husband, a surgeon and writer, was killed in a bombing. A few months ago, she remarried.

Before she left to continue searching the stacks, Nadawi recited an Arabic proverb: Movement, she said, is good.