Design’s democratic leader

Live in style as Dubai-based interior designer Pratyush Sarup takes us into the world of interior design through this fortnightly feature

Soon after returning from Dubai, where the British starchitect was invited by Downtown Design to headline their first design talk of 2015, Asif Khan was sitting at a dinner table with a noted architectural historian. “I was talking about my trip to the Emirate when the gentleman declared, ‘that is one city I couldn’t care less about’”, he recalled, as we sank into the warm, worn comfort of a coffee shop near his Vyner Street studio in London. It turned out the historian had never visited our city. “How can you be an architecture, design or arts historian and ignore Dubai?” says Khan, airing his thoughts. “Dubai is where architectural and cultural history are developing in front on our eyes, at a pace seldom seen before.”

In fairness, Khan is the first to say he’s a new convert. He’d been using Dubai like the many jet-setters do — an aviation hub. The emirate kept cropping up in conversations at design fairs the world over; Downtown Design’s invitation finally got him to experience our world. “Like that historian, I had a lot of preconceptions about what Dubai was. Construction without direction, forward looking, a place of continuous urban change with little evolution at the smallest urban levels.”

He happily stands corrected. “What really makes Dubai is the many layers of its people. From locals who have seen the city boom to expats who have made Dubai their home — there is so much humanity in the city — that was really unexpected. As the urban plan of the emirates is slowly unveiling its larger perspective, that positive energy and the cultural mix of old and new is now emerging at the city level.”

Born in Forest Hill in 1979 to social-worker parents from Tanzania and Pakistan, Khan was encouraged to look beyond his immediate circumstances from a very young age. “Dinner-table conversations were about being aware of others, of being able to serve. And when you have your parents retelling specific cases, these values no longer remain platitudes.”

For a child whose favourite toys were his electrical play-kit, architecture provided a perfect mix of design, technology and social response. He studied at the Bartlett School at University College London, then the Architectural Association, winning top honours at both institutions. In 2007, he set up his independent practice.

One of Khan’s first projects to grab media attention — a fish and chips shop on West Beach, Littlehampton — served a healthy dose of design democracy. Designed to completely open its front to welcome the surroundings, the project still remains a great example of design as a tool to human connection.

“Somewhere between high-design and suburbia — that is a good space to design something,” he says. “Architecture and design are like water — a basic requirement; but whose quality can really influence life. A built environment has a noted impact on health and aspiration. I want my works to enrich people’s lives — even if for a little while.”

From the 2012 Olympics Coca-Cola Beat Box pavilion — with its touch-sensitive walls thumping to the beats of British music producer Mark Ronson when touched — to digitally recreating onlookers’ faces in 3-D at the MegaFaces pavilion at Sochi Winter Games, Khan has utilised his childhood fascination for technology to invite people into the till-now-elitist world of design.

“I don’t like using technology to create make-belief,” he says. “I like it when we can use it to involve people and not just deliver them a hard and defined experience but allow them to create their individual experience for themselves.” Khan’s manner of integrating technology into his works to create intuitive experiences plays with the plasticity of the human mind, allowing it to imagine but within the realms of its understanding. To create these authentic experiences, Khan has assembled an in-house team of programmers and architects.

Slim as his body of work may be, Khan’s fast upward trajectory is built on the back of projects that are genuinely engaging and thought provoking. They equalise society when you step in and resonate with the people of today. True to the times we live in, his worldwide recognition is often credited to a well-balanced mix of eye-popping, press-grabbing, mega-watt sponsor-ridden projects, social-media savviness that some of the biggest names in his field lack and a genuine wish to demystify design at the cost of seeming media-friendly. All things that make him a sitting target for his critics.

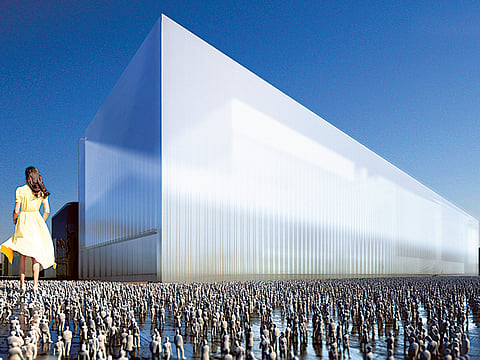

Being shortlisted for the international architectural competition to build the Guggenheim Helsinki is sweet vindication then, as the Guggenheim shortlist was drawn up by a jury who did not know the names of the entrants. From being one among 1,700 to one among six is a huge achievement in itself, but to Khan it is knowing that the jury understood his team’s intent that makes it all worth it.

“I’d been visiting Finland since I was a student. My wife and I have built memories and friendships there that thrive to this day.” He says he owes his deeper understanding of living with nature to the Finnish way of life. And it helped that he knew the site very well, having visited it every time he went to Finland. “I saw that as a sign,” he says about the happy coincidence. “I felt a responsibility to the region to return the knowledge I have been accumulating there and use my knowledge of architecture to give back to the community.”

With their entry, Khan and his team — which includes Finnish design talent, boat builders and architecture historians — salute Helsinki’s incredible history of movements coming up from the grassroots. “We wanted the project to be a porous enough vessel for that region — culturally, ubarbanistically and ecologically. Yes it’s a Guggenheim, but for me, it’s a Helsinki museum and that was the most important guiding factor in our intent.”

From Helsinki to Abu Dhabi, our talk veers to the world-class museums the UAE will be hosting soon. From personal collections to public ones, art has long been exchanged and traded. When it comes to museums such as Louvre and the Guggenheim establishing new outposts, it signals a new era in the evolution of its new location and the aspirations of the people.

“I think it is the responsibility of every global city to bring familiar cultural media to its people,” he says. What is more important though is that this exchange have a trickle-down effect on the regional communities. “These massive investments should eventually act as a springboard for the local creative communities to grow. Rather than a selective clique of creatives travelling abroad for international exposure, an entire cross-section of the local community will have the opportunity to see different vocabularies, techniques, even thought processes at their doorstep.”

Khan can already see that happening in the UAE. “The Burj Khalifa and the development around it has done a stunning job drawing people into an urban space and creating a moment of it all,” he says. “What is interesting is to note that this mega project has now led to the development of the finer grain of the city.” He is talking about the many projects the Dubai government has dedicated to the refurbishment of the local, small scale communities. “Revitalising the forgotten sectors will tie them back to the public realm of Dubai as we know it now.”

Pratyush Sarup edits the design site designcarrot.net. You can follow the site on twitter @DesignCarrot.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox