It’s an unfair and brutal truth: “The more women talk, the more men turn off,” says Nina McLemore. “One of the challenges for women is to learn to say fewer words in a lower voice.”

To be clear, McLemore doesn’t condone this prejudice. As a former executive at Liz Claiborne, she has always encouraged women to speak up. But she is a pragmatist. “We have unconscious biases we don’t know we have and not a lot of control over. We have to accept it and work around it.”

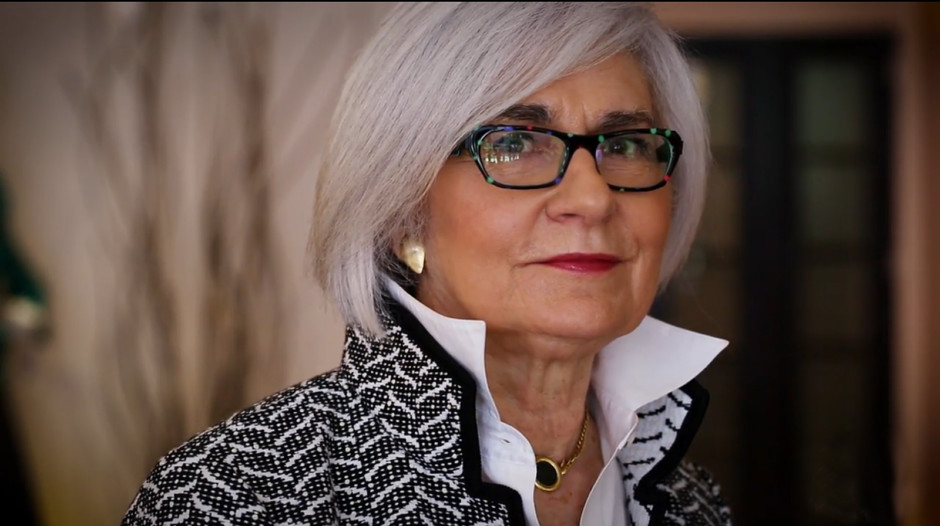

Nina (NINE-uh) McLemore is not a speech coach or life coach. She’s a fashion designer who advises female clients on how to dress for work — to land the promotion, reel in a client, state her case, win the election.

And in particular, she has made a name for herself with her softly tailored jackets, which over the years have both shielded and celebrated women such as Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, Senator Elizabeth Warren, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan, White House senior advisor Valerie Jarrett — and yes, the self-described “pantsuit aficionado” herself, presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton.

These are blazers you probably haven’t even noticed. You’re not supposed to. As the retail industry suffers a multitude of upheavals, the McLemore jackets have filled a niche, overlooked by the likes of Giorgio Armani and St John Knits, as the uniform for a woman of a certain level of authority. They’re not only designed to balance out a woman’s proportions or distract from a problem area — but to communicate power.

Not power as sketched out by Hollywood and Seventh Avenue, which tend to merge sex and ambition with skirts that are short, dresses that are tight and jackets that fit like a vise — but the version of power that strides briskly through blue-chip law firms, investment banks, the halls of Congress and, perhaps, the Oval Office. Power accessorised with a pair of sensible pumps.

Her signature jackets are cut with a narrow shoulder but a full back.

“Women are self-conscious about the shoulders being too big,” she says. But a woman’s got to be able to raise a gavel or gesture emphatically, so McLemore eschews the tight, high armholes favoured by high-end designers.

Her sleeves run about an inch longer than average, and she crafts 2 1/2-inch-lined cuffs so a woman can turn them up in a get-to-work posture. This aesthetic quirk also allows women to buy them off the rack, without seeing a tailor to adjust the sleeve length. Women, McLemore says, don’t like dealing with a tailor.

The collars stand up to frame the face and to elongate the body. And McLemore isn’t going to mince words: Long-and-lean is good.

McLemore came to be the guru of the power set after a dozen years at Liz Claiborne, where she launched accessories and sat on the executive committee. Moving on, she got her MBA from Columbia University, worked in venture capital and fancied herself a bit of a ski bum. Then a few women with sizable incomes and plenty of clout — bankers mostly — complained to her that they couldn’t find anything to wear to work, and asked whether McLemore, as a favour, would help them shop.

After marching these women in and out of boutiques along New York’s Madison Avenue, McLemore recognised their problem. High-end fashion lines had turned their focus towards trendy customers from China and other developing markets rather than catering to the more quotidien needs of those in the retail-saturated United States. And designers had also made the false assumption that baby boomers had aged out of fashion. They were all chasing millennials.

Armani had become obsessively committed to men’s-wear-style tailoring and a neutral palette that did not play well on television. St John, once beloved for its wrinkle-proof separates, had hired Angelina Jolie as a brand ambassador and ratcheted prices upwards. While Akris, a favourite of former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, still offered exquisite tailoring, it had become more pricey than most women can bear. And frankly, many accomplished women in their 50s and 60s were simply not ready to embrace the new power uniform as flaunted by gym-buff 40-somethings like Michelle Obama and the entire female on-air staff of the Today show: the sleeveless, form-fitting sheath.

In other words, fashion had left a lucrative market in the lurch.

When other designers talk about their inspirations, they often drift into poetic reveries about an art exhibition that moved them, a film that haunted their dreams or a landscape that left them in awe.

McLemore, on the other hand, is more likely to explain her creative process with sentences that begin, “There’s a very interesting study ...”

Our brains, she says, make snap assessments about people that can determine everything from who gets hired to who we talk to at a cocktail party. We remember how someone looked more often than we remember exactly what they said. So, look capable, look confident, look good.

In spring 2003, McLemore debuted her collection of jackets, trousers and shirts for the kind of women who live a good portion of their professional lives on C-SPAN, CNN and PBS. She offered them comfortable tailoring in TV-friendly colours, fabrics that don’t wrinkle and at a cost — about $800 (Dh2,938) for a jacket — that’s a good 40 per cent less than the usual designer prices.

Her clients could afford to pay more, but those who have constituents rather than shareholders are loathe to be known for running up their American Express with $4,000 Akris blazers or a $12,000 Giorgio Armani leather coat, of the kind that Clinton recently drew criticism for reportedly wearing.

Although she calls the District of Columbia home, McLemore’s company is based in New York, and she manufactures most everything in the city’s Garment District. Of all her designs, three jacket styles stand out: the Suzanne, the Retro, the Car Coat.

The Suzanne, which is Warren’s preferred silhouette, flatters slender women with lines that gently follow the body. A jacket with a (American) size 8 bustline, for example, eases out to a size 10 at the hips. The Retro is a bit longer, covering the tush — we’ve seen it a lot on Clinton. And the Car Coat is longer still; it’s the style McLemore suggests for taller women or those who are thick in the middle but with skinny legs — a shorter jacket would make them look a bit like “a box on toothpicks.”

Every inch of a McLemore jacket is in service to her customers’ authoritative image; there are no flights of fancy. And every straight-to-the-point observation uttered by McLemore is intended to tell a client what she needs to know and not what she wants to hear. How’s candidate Clinton doing? McLemore would like to see her occasionally dress a bit more casually: “She looks very formal. She’s too East-Coast-dressed-up.”

Being on the public stage makes a woman subject to scrutiny. But it’s also an opportunity, McLemore says. The question to ask is not “What do I want to wear?” but “What impact do I want to make ?”