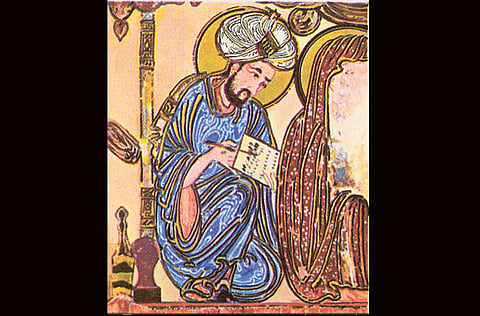

Student of truth

In the 9th century an Iraqi made the daring leap to find common ground between Greek philosophy and Islamic revelation

Abu Yousuf Ya‘qub Ibn Ishaq Al Kindi (c800-870) is hailed by many thinkers as the first Arab philosopher. He served as a true scholar under the caliph Al Ma'mun, whose reign ended in 833, and was associated with the court of his successor, Al Mu‘tasim, who reigned until 842. Educated in Baghdad, his philosophical career peaked under Al Mu‘tasim, to whom Al Kindi dedicated his most famous work, On First Philosophy, and whose son Ahmad he tutored. Although the Iraqi-born philosopher worked with a group of translators, chiefly Syrian Christians or of Syrian extraction, his focus on Aristotle, the Neo-Platonists, and Greek mathematicians and scientists was not merely to translate these works into Arabic. Rather Al Kindi's own treatises, including the Theology of Aristotle, The Book of Causes, and especially On First Philosophy, were all original works that argued the world was not eternal and that God's greatness lay in his simplicity. To be sure, Al Kindi's own thoughts were suffused with Neo-Platonism, though his forte in philosophical matters was Aristotle. He wrote numerous works on other philosophical topics, especially psychology (including the well-known On the Intellect), cosmology and mathematics. A true polymorph, this original thinker helped generations of successors tackle critical issues of concern, which honed on power, helped shape social norms, and enhanced our understanding of religion and the sciences.

Life and times

Born in Kufah, Iraq, into the royal Kinda tribe, which originated in southern Arabia and played a critical role in the early history of Islam, Al Kindi was at the centre of Arab culture and learning in the 9th century. At the time, few could receive a better education in the realm, and while details of his early life are scant, the young man's father was the governor of Kufah (as was his grandfather) — which explained various privileges.

A few years into adulthood, Al Kindi moved to Baghdad to complete his studies, where his scholarship attracted the caliph's attention, coincidentally as the enlightened leader set up the "House of Wisdom" in his capital city.

Al Ma'mun conquered Baghdad in 818 — though he became caliph after defeating his brother in 813 — and was anxious to assemble true knowledge as it was then available. A genuine patron of learning, his academy sought to harvest what was then a Greek monopoly on philosophical and scientific erudition, which prompted him to hire translators whose sole task was to render into Arabic the Hellenic corpus. Al Kindi was thus appointed along with such luminaries as Al Khwarizmi and the Banu Mousa brothers, though the latter three — Jaafar Mohammad, Ahmad and Hassan — excelled in mathematics. All worked in a library of manuscripts that rivalled its burnt counterpart in Alexandria.

Caliph Al Mu‘tasim entrusted his son's education to Al Kindi who had, by then, attained a rare position of trust. Regrettably, the caliph's two successors, Al Wathiq and Al Mutawakkil, were not as enlightened and may have preferred religious indoctrination. Al Kindi and several colleagues in the academy saw their scholarly stars fade, as Baghdad under Al Mutawakkil displayed intolerance. Persecution of non-orthodox and non-Muslim communities followed, and though Al Kindi espoused orthodox Islam, he rejected extremism in all its forms. In fact, all of his philosophical writings focused on the compatibility of Islam with the pursuit of philosophical investigations, which defined modernisation par excellence. Such views, however, set off rivalries.

Surprisingly, though Al Kindi learnt Greek, he was not fluent in the language. That meant he could not have translated original texts himself. This was important because his commentaries on many Greek works, including the writings of Aristotle, whom he admired, Plato, Proclus and others all opened new windows of knowledge without strangulating his thoughts. Consequently, while Greek authors influenced some of his contributions, a much larger invention distinguished him, with hundreds of treatises on a wide variety of scientific and philosophical disciplines. Ibn Al Nadim, the 10th-century bookseller, provided a full Fihrist of these works, though a single manuscript survived in Istanbul, which contains most of Al Kindi's extant philosophical writings.

Philosophical ideas

Although Al Kindi was the first real Muslim philosopher, he reinterpreted many ideas within the Neo-Platonic framework, especially with respect to metaphysics.

Indeed, the erudite man's quest to better understand the nature of God as a causal entity distinguished him from the Mu‘tazilite school of theology, even if he agreed with the latter on maintaining the pure unity of God (Tawhid). Nevertheless, what Al Kindi disagreed, including the Mu‘tazilite beliefs in atoms, was far more important. He concluded that the very goal of metaphysics — the knowledge of God — was indistinguishable from religion. For Al Kindi, philosophy and theology were both concerned with the same subject and not to be separated. Of course, philosophers such as Al Farabi and Ibn Sina, among others, strongly disagreed with such interpretations, arguing that metaphysics was in reality concerned with quasi being, and as such, the nature of God was purely incidental.

Still, it was critical to understand Al Kindi's vision: Metaphysics explained things that subsisted "without matter and, though they may exist together with what does have matter, are neither connected nor united to matter". Consequently, the oneness of God was affirmed, which was sufficient to praise the creator. God's oneness could not be shared with anyone or anything else. Yet, he also defined the "one" as "many", perhaps in the two analogies he discussed in his works: While the human body is one, it is also composed of many different parts, or that a person might see an "elephant" by which he means "I see one elephant" though the term "elephant" also refers to a species of animal that contains many. With this analogy, only "God is absolutely one, both in being and in concept, lacking any multiplicity whatsoever".

Following Neo-Platonic philosophers — who asserted that the universe existed as a result of God's existence — Al Kindi conceived of God as an active creator. He firmly believed that God was an "agent" or efficient cause. This view was expressed in a text with the title On the True, First, Complete Agent and the Deficient Agent that is Metaphorically (an Agent). The text begins as follows:

We say that the true, first act is the bringing-to-be of beings from non-being. It is clear that this act is proper to God, the exalted, who is the end of every cause. For the bringing-to-be of beings from non-being belongs to no other. And this act is a proper characteristic (called) by the name "origination".

Clearly, Al Kindi assumed that the "world of the intellect" was beneath that of God, as he believed that by creating the heavens and setting them in motion, God indirectly brought about things in the sublunary world. This was especially significant in the development of Islamic philosophy, as it portrayed the "first cause" and "unmoved mover" of Aristotelian philosophy as being entirely compatible with the concept of God according to Islamic revelation.

Soul and the afterlife

Al Kindi argued that the soul was a simple, immaterial substance, "related to the material world only because of its faculties which operate through the physical body". To explain the nature of our worldly existence, he compared the soul to a ship that has, "during the course of its ocean voyage, temporarily anchored itself at an island and allowed its passengers to disembark". Passengers who lingered far too long on the island could be left behind when the ship set sail again. Remarkably, this conceptualisation reflected Stoicism par excellence, which cautioned that destructive emotions resulted from errors in judgment. A wise individual who sought moral and intellectual perfection would learn how to control such emotions. Thus, for Al Kindi, as for many philosophers, a person ought not become attached to material things, as these will invariably be taken away from us. Acknowledging a brilliant Neo-Platonist idea, Al Kindi further opined that our souls could either be directed towards the pursuit of desire or the pursuit of intellect. He strongly believed that the pursuit of desire would tie a soul to the body, which means, at least logically, that when the body dies, it will also die. Yet, if the soul is the pursuit of the intellect and is free from the body, it will survive "in the light of the Creator" in a realm of pure intelligence.

Revelation and philosophy

A believer who accepted that prophecy and philosophy were two different routes to arrive at the truth, Al Kindi contrasted the two positions in four different ways, which further revealed his philosophical views. First, and based on his own experiences, Al Kindi understood that a person must undergo a long training and study period to become a philosopher. This was not a requirement for a prophet since only God could bestow divinely inspired wisdom upon someone. Second, the philosopher, whether he was a believer or not, strove to arrive at the truth by relying on his intellect. The prophet learnt the truth as God revealed this to him. Thirdly, the prophet's thoughtfulness, lucidity and inclusiveness were all superior to those of the philosopher, because these were divinely rendered. Finally, the way in which the prophet is able to express his perceptions to believers is incomparable to that of the philosopher who, through perseverance and diligence, needs to invent persuasive methods.

These were the key reasons why Al Kindi concluded that the prophet is "superior in two fields: the ease and certainty with which he received the truth, and the way in which he presented it". What the erudite Iraqi added, however, was critical to our overall understanding of his vision. Al Kindi affirmed that the content of the knowledge revealed to the prophet and that processed by the philosopher was the same. Of course, this was and remains a highly controversial issue but entirely Kindian.

It was further critical to note that Al Kindi adopted a naturalistic view of prophetic visions. He claimed that, through the faculty of "imagination" (in Aristotelian philosophy, it is the process by which an image [phantasma] is presented to us, not the common interpretation that focuses on fantasy, inventiveness, idiosyncrasy, and insightful thought), purer souls could receive wisdom. This is sometimes mistakenly referred to as a person with a sixth sense. Rather, Al Kindi did not believe that such visions, or dreams, were "revelations from God". Instead, he explained that imagination enabled a human being to receive the "form" of something without needing to perceive the physical entity to which it referred. Logically, therefore, anyone who was purified — through a variety of ways — could conceivably receive such visions. This was rejected by Al Ghazali, the great Persian philosopher, who criticised the idea in his Incoherence of the Philosophers.

Naturally, Al Kindi appreciated the usefulness of philosophy in answering questions of a religious nature, though many Muslim thinkers abandoned such pursuits. While some opposed philosophy simply because it was perceived as a "foreign science", Al Kindi discarded such objections. Addressing this precise point, he wrote: "We must not be ashamed to admire the truth or to acquire it, from wherever it comes. Even if it should come from far-flung nations and foreign peoples, there is for the student of truth nothing more important than the truth, nor is the truth demeaned or diminished by the one who states or conveys it; no one is demeaned by the truth, rather all are ennobled by it.

"Leading theologians almost always criticised the conclusions arrived at by the philosophers, rarely their persona. Even the great Al Ghazali relied on logic to offer his explanations, which made him a philosopher par excellence, though he asserted that many philosophers arrived at theologically erroneous conclusions."

Legacy on Arabs and Muslims

Al Kindi's optimism faded a century or so after his death, though among thinkers he influenced one could discern a tendency to harmonise "foreign" philosophy with "indigenous" Muslim interpretations. The "Kindian tradition" in the 10th century was the work of his students, especially Al Amiri, a well-known Neo-Platonist thinker. Ironically, while authors writing in Arabic later than the 10th century rarely cite Al Kindi, European philosophers relied on his massive corpus for generations, including on numerous works dealing with astrology, optics, mathematics and psychology. Fortunately, some of his books — such as the On the Intellect opus — only survived because they were translated into Latin and preserved in European libraries.

To be sure, Muslim philosophers espoused legacies that surpassed those of Al Kindi, though there is no denying that he set a process in motion. No only did the Kufahan rely on Greek masters, which he made sure his contemporaries and successors learnt and digested, Al Kindi did not reject fundamental Aristotelian interpretations. Naturally, major authors such as Al Farabi and Ibn Rushd abandoned the Kindian method, but this was the result of an intrinsic aversion to philhellenism. Ironically, while few mentioned him by name in their writings, most carried out Al Kindi's fundamental project, which married a full-fledged engagement of foreign ideas with the practice of philosophy.

Dr Joseph A. Kéchichian is the author of the forthcoming Legal and Political Reforms in Saudi Arabia (Routledge, 2012).

This article is the first of a series on Muslim thinkers who greatly influenced Arab societies across the centuries. Its purpose is to introduce philosophical ideas that left a marked impact on individuals, both at the elite level as well as within the intelligentsia.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox